When Robert Moses Wiped Out New York’s ‘Little Syria’

What Happened to the Former Main Street of Syrian America

“I feel like saying today, ‘At last,’ because for some time there was some dispute as to whether we would cross the East River between Manhattan and Brooklyn under the water or over the water,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt told a few thousand invited guests at a groundbreaking ceremony in Red Hook, Brooklyn, on October 28, 1940. “And they told us—the Army Engineers—looking way, way into the future, we hope so far away that none of us will live to see it, there might be an attack on America, and if that attack were to come it would be safer for America and all its cities if we could have this tunnel instead of that bridge.”

The cost of the tunnel was projected at $81 million, but Roosevelt assured the politicians present, including the mayor, the governor, and other top officials, that the tunnel would eventually “pay itself out” from the tolls it collected. With that, he “pulled a cord attached to the whistle of a steam shovel,” reported The New York Times, “and as the signal sounded, Louis Cappola, operator of the shovel—a crane type—dropped the great steel ‘bucket,’ opened its jaws, took a big bite of earth, and dumped the soil into a ten-ton truck.”

Groundbreaking ceremony for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, October 28, 1940, in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

Groundbreaking ceremony for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, October 28, 1940, in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

It would have been hard to overstate the extent to which President Roosevelt and Robert Moses, then chairman of the Triborough Bridge Authority, held each other in contempt. Moses was no mere bureaucrat running a bridge authority; he was New York City’s fabled and feared “Master Builder” and “Power Broker,” responsible for the Whitestone and Triborough Bridges, Jones Beach, hundreds of playgrounds, and nearly a dozen enormous public swimming pools, among other popular projects. Few and far between were politicians willing to cross him.

“Expediting auto traffic to suburbia took priority over the community of politically powerless city dwellers.”Roosevelt and Moses had been feuding as far back as 1924, when the two clashed over funding for the Taconic State Parkway. (Roosevelt was then chairman of the Taconic State Park Commission; Moses was president of the Long Island State Park Commission.) Now Moses wanted another soaring bridge—not an unsightly tunnel—to connect Brooklyn to Lower Manhattan, and he was determined to prevail over his old nemesis, now president of the United States.

But the Power Broker met his match as community groups, civic leaders, historic preservationists, Wall Street executives, and the mayor and the governor, not to mention friends of the New York Aquarium at Castle Garden—which would have been demolished to make way for the bridge—closed ranks in opposition to his imperious plan. “A bridge with its terminus and approaches at the Battery will seriously disfigure perhaps the most thrillingly beautiful and world renowned feature of this great city,” wrote one opposition group.

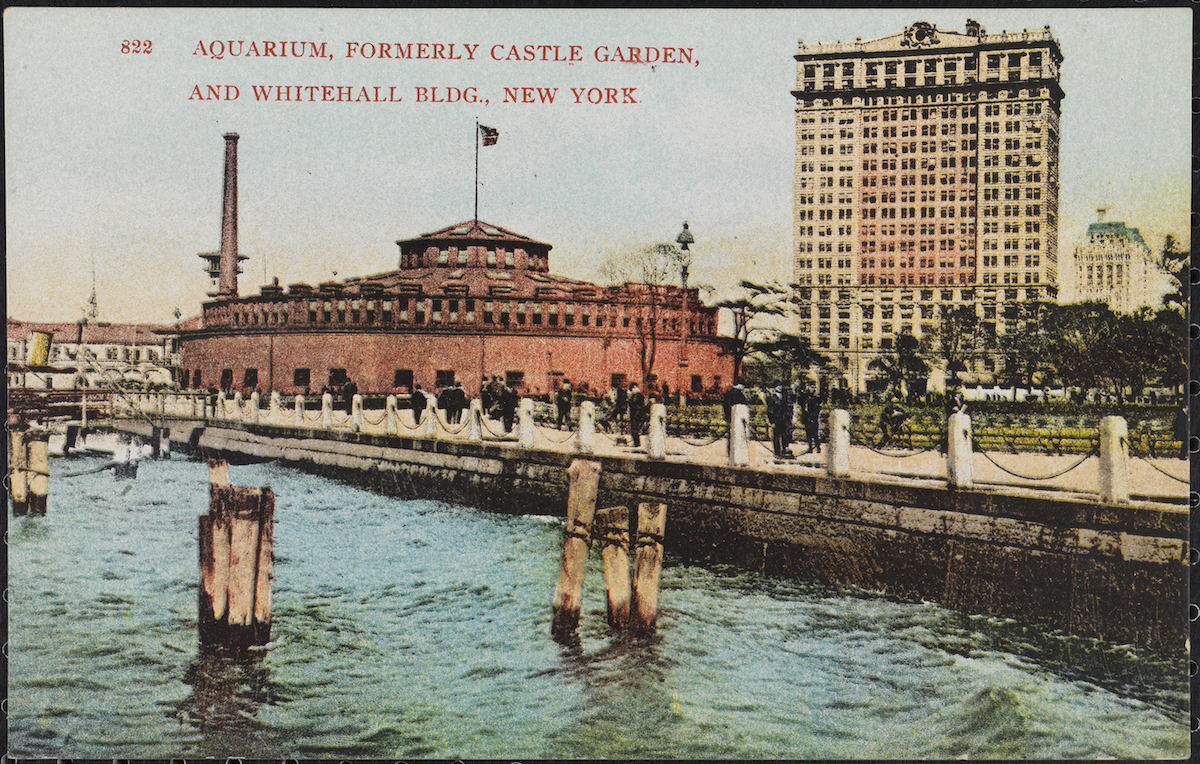

The New York Aquarium with the Whitehall Building in the background, circa 1905. Image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

The New York Aquarium with the Whitehall Building in the background, circa 1905. Image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

But it was ultimately the secretary of war Harry Woodring, who intervened, scuttling Moses’s bridge because it was “seaward of a vital naval establishment,” the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Reportedly out of spite, Moses took retaliatory aim at the aquarium, one of the city’s most popular attractions, shuttering it on the dubious grounds that construction of the tunnel would undermine Castle Garden’s fragile foundation.

The last remnants of Little Syria were demolished in the early 1940s to make way for the entrance ramps to the tunnel. “Expediting auto traffic to suburbia took priority over the community of politically powerless city dwellers,” New York University professor Jack Tchen wrote in his 2002 essay, “Whose Downtown?!?” “The Syrians had to leave and restart their businesses and their lives somewhere else.”

An elevation drawing of St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church at 103 Washington Street, 1929. The building was landmarked in 2009. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

An elevation drawing of St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church at 103 Washington Street, 1929. The building was landmarked in 2009. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

“Most [Little Syria] residents were Christian, their loyalties divided only between St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church at 103 Washington Street and St. Joseph’s Maronite Church at 57 Washington Street,” wrote The New York Times’ David Dunlap in 2012. St. George’s is one of just three remaining buildings from the days of Little Syria and was declared an official landmark in 2009 by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. “It remains Lower Manhattan’s most vivid reminder of the vanished ethnic community once known as the Syrian Quarter,” wrote the commission in its report, “and of the time when Washington Street was the Main Street of Syrian America.”

__________________________________

From A Century Downtown by Matt Kapp. Used with the permission of PowerHouse Books. Copyright © 2020 by Matt Kapp.