When Kathy Acker Interviewed the Spice Girls

"Money makes the world what it is today . . . a world infested with evil."

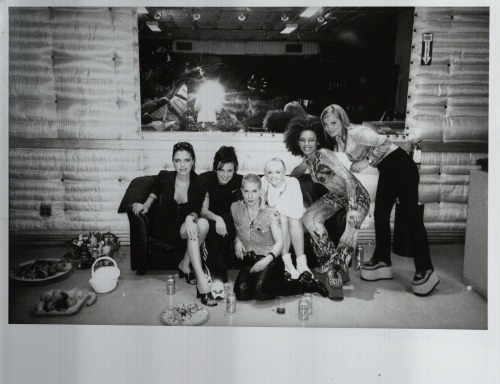

In 1997, The Guardian invited noted experimental writer Kathy Acker to interview the Spice Girls, just as they were at the cusp of mega-stardom (and also their subsequent dissolution) in the US. In fact, on the day of the interview, they were rehearsing for their very first live television appearance—on Saturday Night Live.

At first glance, it may seem a little strange that some editor sent a boundary-pushing postmodern feminist, a writer and performance artist whose work borders on the pornographic, to interview these peddlers of bubblegum-flavored Girl Power. But on the other hand, it actually makes perfect sense. As Hayley Campbell pointed out, Kathy Acker was always obsessed with girl gangs, returning to the trope repeatedly in her work. “If you squinted a bit, maybe the manufactured Spice Girls were the quintessential girl gang: working class women projecting individualism and spreading the word of some kind of feminism that was palatable to their teenage fans.” There’s something quite alluring about the idea of these two different kinds of feminism—one underground, the other mainstream, one hard-won, one brand new—coming together. (Though for all this talk of new and old, from my current vantage point, the Spice Girls’ feminism seems more outdated than Acker’s.)

Acker herself had some hesitations about the interview. According to the Campbell’s BBC show Unpopped, there’s quite a bit of unpublished material around the interview; in what was presumably an earlier draft of the introduction, Acker wrote: “When The Guardian asked me to interview the Spice Girls, whose music I had not yet heard, I looked down at their pictures and the jacket of their album and thought, in my far too rapid fashion, what is this nonsense? And then I thought, I support women, and felt the prick of curiosity.”

In fact, she wound up loving them. “There is a refusal among America’s music critics to take the Spice Girls seriously,” Acker writes in the Guardian piece.

The Rolling Stone review of Spice, their first album, refers to them as “attractive young things … brought together by a manager with a marketing concept”. The main complaint, or explanation for disregard, is that they are a “manufactured band”. What can this mean in a society of McDonald’s, Coca-Cola and En Vogue? However, an email from a Spice fan mentions that, even though he loves the girls, he detects a “couple of stereotypes surrounding women in the band’s general image. The brunette is the woman every man wants to date. Perfect for an adventure on a midnight train, or to hire as your mistress-secretary. The blonde is the woman you take home to mother, whereas the redhead is the wild woman, the woman-with-lots-of-evil-powers.” So who are these Girls? And how political is their notorious “Girl Power”?

Even though I have seen many of their videos and photos, as soon as I’m in front of these women, I am struck by how they look far more remarkable than I had expected, even though Mel C is trying not to look as lovely as she is. I had intended to say something else, but instead I find myself asking them: “If paradise existed, what would it look like?”

If that seems strange as an opening question, Geri’s response is even stranger: “Money makes the world what it is today . . . a world infested with evil. All sorts of wars are going on at the moment. Everyone’s kind of bickering, wanting to better themselves because their next-door neighbour’s got a better lawn. That kind of thing.”

Rather political, then. Acker finds herself awed by the Spice Girls—visually (she keeps returning to their clothes, their beauty), sonically (they keep talking over one another; at times she can’t discern who says what), and, it seems to me, emotionally. They surprise her. “I can’t keep up with these Girls,” she writes.

My generation, spoon-fed Marx and Hegel, thought we could change the world by altering what was out there—the political and economic configurations, all that seemed to make history. Emotions and personal—especially sexual—relationships were for girls, because girls were unimportant. Feminism changed this landscape in England, the advent of Margaret Thatcher, sad to say, changed it more. The individual self became more important than the world.

To my generation, this signals the rise of selfishness for the generation of the Spice Girls, self-consideration and self-analysis are political. When the Spices say, “We’re five completely separate people,” they’re talking politically. “Like when you’re in a relationship,” Mel B takes over, “and you’re in love, you feel you’re only you when you’re with that person, so when you leave that person, you think ‘I’m not me’. That’s so wrong. It’s downhill from then on, in yourself spiritually and in your whole environment. In this band, it’s different. Each of us is just the way we are, and each of us respects that.”

Acker asks the girls about boys. They tell her that they like them. She tells them she’s “never been good at balancing sexual love and work,” and Mel B assures her that it’s possible, that she should demand her own freedom. Acker asks what they want to do—though she doesn’t use this phrase—when they grow up. After the end of the Spice Girls, that is. They all have other, commoner dreams than pop stardom—family, kids, the restaurant business, the movie business. Mel B wants to be a preacher. Acker asks them to describe themselves. They want to run the world.

“They both are and represent a voice that has too long been repressed. The voices of young women not from the educated classes.”

“The Spices, though they deny it, are babes—the blonde, the redhead, the dark sultry fashion model—and they’re more,” Acker writes in closing. “They both are and represent a voice that has too long been repressed. The voices, not really the voice, of young women and, just as important, of women not from the educated classes.

It isn’t only the lads sitting behind babe culture, bless them, who think that babes or beautiful lower and lower-middle class girls are dumb. It’s also educated women who look down on girls like the Spice Girls, who think that because, for instance, girls like the Spice Girls take their clothes off, there can’t be anything “up there.”

The Spice Girls are having their cake and eating it. They have the popularity and the popular ear that an intellectual, certainly a female intellectual, almost never has in this society, and, what’s more, they have found themselves, perhaps by fluke, in the position of social and political articulation. It little matters now how the Spice Girls started—if they were a “manufactured band.”

What does this have to do with feminism? When I lived in England in the Eighties, a multitude of women, diverse and all intellectual, were continually heard from—people such as Michele Roberts, Jeanette Winterson, Sara Maitland, Jacqueline Rose, Melissa Benn. Is it also possible that the English feminism of the Eighties might have shared certain problems with the American feminism of the Seventies? English feminism, as I remember it back then, was anti-sex. And like their American counterparts, the English feminists were intellectuals, from the educated classes. There lurked the problem of elitism, and thus class.

I am speculating, but, perhaps due to Margaret Thatcher—though it is hard to attribute anything decent to her—a populist change has taken place in England. The Spice Girls, and girls like them, and the girls who like them, resemble their American counterparts in two ways: they are sexually curious, certainly pro-sex, and they do not feel that they are stupid or that they should not be heard because they did not attend the right universities.

If any of this speculation is valid, then it is up to feminism to grow, to take on what the Spice Girls, and women like them, are saying, and to do what feminism has always done in England, to keep on transforming society as society is best transformed, with lightness and in joy.

Acker would die in November that year, of complications from breast cancer. That same month, the Spice Girls would release their second album, Spiceworld, and fire their manager, a move considered by some to be the beginning of the end of the group. At the risk of being corny, I’m glad they got to meet. For them—and for us.