When Joan Rivers (Finally) Got Her Big Break

“Thirty-one years of people saying ‘no.’ Ten minutes on television and it was all over.”

It’s a truism of show business that a performer dubbed an “overnight sensation” has often spent years in the trenches before being granted the opportunity, the one moment of magic, that turns him or her into a star. Well, on Wednesday, February 17, 1965, in the final minutes of The Tonight Show, Joan Rivers, who, at the age of 31, had a full decade of experience, found herself in just that situation, and she filled it and seized it and wrung every drop out of it and, son of a gun, transformed herself forever, right there on TV, in front of a nation.

She and Carson had an immediate rapport, his cool and relaxed mien tempering and sanding smooth her frazzled, frantic energy. He asked leading questions about Larchmont, about dating, about her struggles with beauty, about, well, being Joan Rivers, and she knocked each softball out of the park, with Milt Kamen beside her on the couch breaking up just as hard as Carson was behind his desk. She did the bit about the wig being run over by the car, which, by then, she had written into a little symphony of well-honed beats and riffs. When her ten or so minutes were up, Carson, wiping a tear of laughter from his eye, beamed and said, “God, you’re funny! You’re going to be a star!”

She didn’t hear him. She was too frayed, too enervated, too tired from so many years of struggling so hard. She’d had shots before, and they’d fizzled. She was banking on exactly nothing to be true. She made her way through the congratulatory knot of performers and show staffers backstage and drove home to Larchmont to watch the taped show with her parents. She saw that she’d done well, and she heard Carson’s words of anointment. But she was inured to disappointment. It was one a.m. at the end of a long, emotional day, and she had to report to the Candid Camera set early the next morning. She went to bed.

Funny how the mind can work. She thought that, at best, maybe they might want her back on the show sometime. It seemed to go well enough, after all. But she almost didn’t dare hope. She had been hungry—famished—for success for so long, and she had failed to attain it so regularly, that she got up, went to work, and waited hours before she called Roy Silver to find out what they’d said about her.

“Jesus Christ!” he shouted. “Where have you been? The phone has been ringing off the hook…. You’ll never make under $300 a week for the rest of your life, I guarantee it.”

He told her to go out and find a New York Journal-American, in which columnist Jack O’Brian had written, “Johnny Carson struck gleeful gold again last night with Joan Rivers … an absolute hilarious delight. Her seemingly offhand anecdotal clowning was a heady and bubbly proof of her lightly superb comic acting; she’s a gem.” Silver told her that she had indeed been invited back to The Tonight Show—in two weeks, in fact—and he wanted her to come in, immediately, if not sooner, to sort through the dozens of opportunities that suddenly lay before her.

She quit Candid Camera. She called home to share the good news, and she learned from her mother that their phone had been ringing all day with well-wishes. (Meyer proudly told one and all, “Of course, we always knew”). And she headed out into the light of day and the future that she had scrapped so hard for so long to build for herself.

If she felt that she was on top of the world, the world seemed happy to remind her that she was still a girl trying to make her way in a man’s business.

“It was all over,” she realized. “Thirty-one years of people saying ‘no.’ Ten minutes on television and it was all over.”

Roy Silver wasn’t exaggerating when he said there were more offers for Joan’s services than he knew what to do with. In the coming weeks, he got her a proper agent at General Artists Corporation (home, of course, of super-agent Buddy Howe and comedians Jean Carroll, and, for a while, Phyllis Diller). He arranged a lucrative multiweek residency for Joan to headline at the hungry i in San Francisco and a similar gig at Mister Kelly’s in Chicago, as well as stints in Pittsburgh and Dayton and one-night stands on the college and nightclub circuit all over the country. He got her a deal with Warner Bros. to record a live LP that would be stitched together from her shows in San Francisco and in New York, where Fred Weintraub was keen to feature her at the Bitter End. He booked her for a number of high-profile TV slots, including a fresh chance with Jack Paar, who had his own chat/variety show in prime time (Joan’s welcome was assured by having Silver’s top client, Bill Cosby, on the same episode). He got her a first-look deal at NBC to develop comedy shows (none were ever realized). And he made her a regular on The Tonight Show, where she and Johnny Carson honed their improvisatory rapport on five more installments before the summer ended.

And in a truly stunning instance of kismet, of wish fulfillment, of having it all, those appearances alongside Carson led her to, of all things, a husband.

Edgar Rosenberg was a publicist and producer working for an arm of the United Nations, and he needed a comedy writer to rework a script he was developing as a feature film to star Jack Lemmon. In June 1965, he contacted an acquaintance at The Tonight Show and asked if there was an appropriate writer on staff for such a job. His friend mentioned that funny comedy writer they’d been featuring recently, Joan Rivers. Rosenberg invited Joan and Roy Silver to dinner at a French restaurant. He sent a limousine, which picked Joan up from her new apartment above the Stage Deli on Seventh Avenue.

Rosenberg was everything Joan’s mother had raised her to admire in a man: educated, well mannered, impeccably dressed, gracious, apparently wealthy—classy, in a phrase—and a lifelong bachelor. He was born in Germany in 1925 to a prosperous Jewish butcher and his wife, and his family had fled, via Copenhagen, to Cape Town, South Africa, where he was raised, a loner who read books voraciously and was housebound with a case of tuberculosis (a disease that so shamed him that Joan didn’t learn he’d once had it until she’d known him for some 20 years). He attended Rugby School and the University of Cambridge in England, then came to America in the late 1940s, working as a bookstore clerk and a functionary at an advertising agency before entering show business, first as a budget supervisor at NBC and then as a producer of public service films for the network.

From there, he moved to the public relations firm headed by Anna Rosenberg (no relation), whose company helped such entities as governments, corporations, politicians, and, most notably, the United Nations express their purposes to the world. Edgar produced promotional films and televised events for the firm, and in the course of his work, he made the acquaintance of scores of major players in the entertainment industry. His prospective Jack Lemmon movie was an outgrowth of those relationships, a first foray into independent film production.

The dinner went splendidly. Not only was Joan enticed by the chance to write a feature film for Lemmon, but she was intrigued by this formal, cultured man with the British accent who seemed so worldly and connected. A few days later, Joan and her soon-to-be boss had a second dinner, without her manager, at the super-exclusive Four Seasons. The evening confirmed her initial impression: she was interested.

The deal was signed, and Rosenberg suggested that Joan join him, her co-screenwriter, novelist Eugene Burdick (Fail Safe, The Ugly American), and Lemmon himself in Jamaica for a getaway conference at which they’d rewrite the script. If it was a setup by Rosenberg, it was an elaborate one. The party, which also included another producer, Christopher Mankiewicz, and his wife, was to be housed in bungalows at the posh Round Hill resort near Montego Bay. En route from the airport, they learned that Burdick would not be coming and that Lemmon would be delayed.

Joan might’ve been a promising freak, an attractive freak, but she was no less freakish for the fact.

Joan was on guard: “I did not want to be a date. I wanted to be a professional screenwriter,” she recalled. But Rosenberg was a perfect gentleman, never once suggesting anything other than professionalism and friendliness. And then the Mankiewiczes left, and Joan and Rosenberg were alone, with no work to do and no one to distract them. Joan phoned Treva Silverman in New York and begged her to come down and serve as, in effect, a chaperone. But before Treva could arrive, the seemingly inevitable happened. Joan went off for a swim, and when she returned, “there was Edgar, standing in the doorway. Suddenly, when I saw him, I had a deep sense of well-being, of coming home, a certainty that he was what I had been looking for, that this was absolutely right.” They made love, and as they lay together afterward, he proposed, and she accepted.

They were at once an odd couple and a good match: he gave her breeding and respectability, she gave him vitality and humor. They both came from places of privilege yet felt underestimated by the world around them. They believed that their show business talents and aspirations could mesh. They were a good physical match, the tiny Joan not remotely threatening to overshadow her short husband-to-be, even in heels. Yes, he could be stiff and cool and awkward, and she could be strident and needy and neurotic. But those qualities seemed to link them, like teeth in a set of gears. They barely knew each other, but they felt like kindred.

When they returned to New York, Joan moved in with her new fiancé. Three days later, on July 15, at a courthouse in the Bronx filled with Filipino sailors and their new brides (“the first and last time that Edgar and I were the tallest people anywhere,” she said), they were married. They had known each other less than a month. And that night, Joan worked: two sets at the Bitter End, where Fred Weintraub refused to give her the night of her wedding off unless she could get Woody Allen or Bill Cosby to sub for her.

As a bonus, she had a new font of material: “I married Edgar right after I met him. I figured I didn’t have long until he got sober. My honeymoon was a disaster. He wanted to have sex 12 times. I said, ‘Edgar, please be reasonable. We can’t afford that many hookers!’”

If she felt that she was on top of the world, the world seemed happy to remind her that she was still a girl trying to make her way in a man’s business. Just two days before her wedding, the New York Times’s Robert Alden wrote about her in a profile that read as the most backhanded heap of compliments imaginable. It was the paper’s first-ever article about her or her work, and it began:

Women comedians like women shot-putters come to their profession with a certain handicap. Traditionally, women are supposed to be beautiful, seductive, gentle and fair—not funny or muscular. But through the years and despite the handicap that these metiers do not come naturally to them, women shot-putters like women comedians have existed and thrived.

After this appalling lead, Alden continued on, offering what was, essentially, a favorable opinion in a nonetheless barbaric tenor:

A new comedienne of ripening promise … an unusually bright girl who is overcoming the handicap of a woman comic, looks pretty and blonde and bright and yet manages to make people laugh. Her humor is bright and pointed…. Miss Rivers is quick-witted and inventive…. She improvises with assurance.

But, clearly, the point was made: A woman comedian was, more or less, a freak in the eyes of this one man. Joan might’ve been a promising freak, an attractive freak, but she was no less freakish for the fact.

Joan continued to rise under Silver’s sure hand, abetted by General Artists’ clout. By late 1965, her Warner Brothers LP, Mr. Phyllis and Other Funny Stories, had been released to modest success, she was under contract to The Tonight Show for a string of appearances, she had shown up on several TV game, talk, and variety shows, and she had appeared in a lucrative nightclub engagement at the Basin Street East, a tony uptown joint where she drew a salary of $2,000 a week as the opening act for Mel Tormé and the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

It was exactly what she had wanted, but, just as Phyllis Diller felt when she signed with GAC, Joan had the sense that she was getting too big too fast. “My agents pushed me toward money deals,” she remembered years later, “rather than the correct moves for my career. I was quickly being destroyed.” As if to prove her point, Roy Silver told the press that he planned to get her into a salary range between $100,000 and $200,000 per year and turn her into “the next Lucille Ball.”

Joan asked Silver to slacken the pace and let her continue to develop her material and her skills in the low-profile, intimate settings that she’d been accustomed to. He told her she was just feeling the nerves one feels when one rockets to fame: “Don’t worry, baby, it’s all in your head. You can do it. You’ve got to. This is the big time.” She talked it over with Edgar, and he agreed with her. In the fall, her contract with Silver expired, and she didn’t renew it.

It was exactly what she had wanted, but Joan had the sense that she was getting too big too fast.

Instead, she signed with Jack Rollins, who finally agreed that she was ready for his services as manager. He booked her into a setting where she truly could shine: Downstairs at the Upstairs, a club on West Fifty-Sixth Street and Fifth Avenue that had the bohemian feel of a Greenwich Village spot. It was, as the name indicated, two clubs, with the Downstairs given over to showcase acts, and the Upstairs, the larger room, set aside for multiperformer musical revues. On the Upstairs stage, the promising likes of Madeline Kahn and Lily Tomlin, among any number of still-unknown singers, comic performers, and cabaret artists, made some of their first notable impressions. Downstairs was more like a private club, a space not unlike the ones in the Village where Joan was so comfortable.

For several years, singer Mabel Mercer had been the chief attraction Downstairs, but Joan gradually made it her own room. She would appear for weeks at a time, testing out new material, polishing her onstage presence, and then taking her act on the road. The intimate room drew a sophisticated crowd—Phyllis Diller came, and laughed louder and harder than anyone; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis came, and ducked her head when Joan scanned the crowd for a woman with whom to launch into some schtick. It was a small enough space for her to work off the crowd but a financial step up from the Village scene and a significant booking in the eyes of TV and film executives.

Rollins, following Roy Silver, convinced Joan that she needed to sharpen her act. She was still given to making esoteric jokes about highbrow culture, her gay friends, her Jewish roots. These were crutches, in Rollins’s eyes, and he taught her that material of that sort had a floor (that is, a certain portion of the audience would always laugh at it) but also a ceiling (that is, only a certain portion would ever laugh at it). She admitted that settling into a new, broader sort of comedy wasn’t yet a natural choice for her. “Two years ago,” she said, “if I had two jokes and one was very hip—I hate the term—and one was very commercial, I would have chosen the hip joke. Now, I choose the commercial joke, because it’s funny to me.”

Under Rollins’s guidance, she developed her talent to its full potential. She used to spew one-liners that often had nothing to do with her life. After working closely with Rollins, she could go for several minutes, building a theme and creating paragraphs, even mini-essays, about, say, getting married later in life than she (or, more to the point, her mother) thought she might:

The whole society is not for single girls. Single men, yes. They’re so lucky. A boy on a date, all he has to be is clean and able to pick up the check and he’s a winner. But a girl: When you go on a date, the girl has to be well dressed, the face has to be nice, the hair has to be in good shape; the girl has to be bright and witty and a good sport—“Howard Johnson’s again! Hooray, hooray!” A girl, 30 years old, you’re not married, you’re an old maid. A man, he’s 90 years old, he’s not married—he’s a catch! … My mother had two of us at home that weren’t, as the expression goes, “moving.” The neighbors would come over and say, “How’s Joan? Still not married?” And my mother would say, “If she were alive!” And I was sitting right there! When I was 21, my mother said, “Only a doctor for you.” When I was 22, she said, “All right, a lawyer, a CPA.” At 24 she said, “We’ll grab a dentist.” Twenty-six, she said: “Anything!” Anyone who came to the door was good enough: “Oh Joan! There’s an attractive young man down here with a mask and a gun!” Catholic mothers have an excuse: “She wants to be a nun! What can I do?” A Jewish mother would be walking around with a bag over her face.

It was a tumultuous working relationship—the breezy, gentle Rollins and the volatile, emotionally needy Rivers—and it wouldn’t last long. But with his help she well and truly found her voice, her calling, during those years doggedly working on her act and, indeed, her very presence on the Downstairs stage.

Rollins got her some plum gigs. She was cast in a small role in The Swimmer, director Frank Perry’s adaptation of a John Cheever story about a man who decides to swim his way across his Connecticut suburb by taking laps in the pools of various neighbors and acquaintances. Burt Lancaster, still as fit as in his days as an acrobat, would play the protagonist, Ned Merrill. Joan was cast as a woman whom he meets at a raucous party. She’s there on a date but chats him up until someone whispers to her that Merrill’s social stock has bottomed out, and she walks away.

She had been so discouraged over the years that she had come to trust only her internal voice and, now, too, the voice of Edgar.

The film premiered in the spring of 1968. Joan’s scene is brief: she has about eight lines—and she gets no close-ups. But she still makes an impact, especially with the vulnerable way she asks, “You, uh, married?”—shrugging and looking away as she says it, but peeking hopefully out from underneath her hair-sprayed coif and false eyelashes, the eternal bachelorette always ready to be disappointed. The film was well reviewed but didn’t do a lot of business. In the New York Times, Vincent Canby mentioned Joan among the several cast members whom he found “especially interesting.” But that wasn’t enough to yield any other film offers.

By then, though, it might not have been possible for her to entertain them. As 1966 ended, Joan had appeared on The Tonight Show some 20 times and was making her Las Vegas debut, at the Flamingo, opening for the French singer Charles Aznavour. She felt entirely unprepared: “I didn’t even have a dress,” she recalled. “I had a plain black dress, and I went out and bought sequins and sewed them on it!” She was still most comfortable in more modest venues, and she always came home to Downstairs at the Upstairs, her small playground, where she packed the house regularly and got the immediate feedback that was so crucial to her not only in developing her craft but in helping her to feel comfortable inside her own skin. She had been so discouraged over the years—by her parents, by dismissive agents and managers, by her own nagging insecurities—that she had come to trust only her internal voice and, now, too, the voice of Edgar.

While Joan battled her demons, wrote jokes, performed, networked, and battled her demons some more, she turned to Edgar for reassurance and to see that all the details were handled—a combination of spiritual confessor and hard-nosed producer. Their partnership allowed her to retract her claws and be the genial, agreeable talent, while he took—indeed, relished—the role of the aggressive, demanding overseer of his client/wife.

Even on familiar turf—the nightclub stages and TV shows where she plied her trade—Joan could still be considered an iconoclast and a danger. She finally got the nod from The Ed Sullivan Show, arguably the only entertainment outlet that carried as much prestige as The Tonight Show, and she was convinced that it was an accident. “He was a little foggy sometimes,” she said of the host. “Right before the show, they had been pitching singer Johnny Rivers to him, and he went out and said, ‘Next week, Joan Rivers!’”

Having accidentally booked her, Sullivan insisted that he see her act first, and he had her come to his apartment at the Delmonico Hotel on Park Avenue and perform it for him and his wife, Sylvia. She was put through the ordeal, she felt, for one reason: “I wasn’t risque at all in those days, but he was very worried about me because I was a woman.” She got the gig, and she did well, and she was invited back several times. Even Edgar found a place in Sullivan’s head, if a mistaken one. “He somehow decided,” Joan recalled, “that Edgar was a doctor, and so for the rest of our relationship he would say, ‘Hi, Doctor, nice to see you, Doctor.’”

Joan’s unsteady rapport with Sullivan would be tested not long after when she was scheduled for a return visit and happened to be eight months pregnant. Being so driven in her career, she had never thought much about motherhood. But she started to feel differently as she hit her mid-thirties and started taking note of other women and their babies. Joan had been on the pill, but she stopped taking it in early 1967, and by April she was pregnant.

Being a neurotic who shared everything and turned it into comedy, she immediately began making jokes about her condition and how she got that way: “I have no sex appeal. If my husband didn’t toss and turn in his sleep, we’d never have had the kid.” But Sullivan wouldn’t allow her to broach the subject on his stage. In fact, he wouldn’t even let her use the word pregnant. Instead, she was forced to stand there, visibly with child, and declare, “I’ll soon be hearing the pitter-patter of little feet.”

It wasn’t often that she compromised. Pregnant though she was, she kept doggedly working. On the night of January 19, 1968, she was onstage at the Downstairs when she started to feel contractions. She finished her set, sat for an interview with a newspaper reporter, went home, and went to bed. The next day, she woke at noon and went to the hospital, where she delivered her baby, Melissa Warburg Rosenberg, after only a couple of hours of labor.

It was yet another episode of wish fulfillment for the doctor’s daughter from Larchmont: career, husband, and now a child. She had achieved a state that had eluded her for more than a decade. Not, of course, that she was above making jokes about it: “Having my daughter, I screamed and yelled for 23 hours straight. And that was just during the conception!”

_________________________

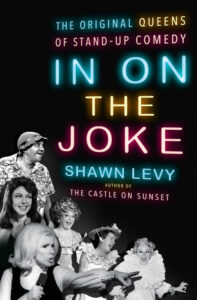

Excerpted from Shawn Levy’s In on the Joke: The Original Queens of Standup Comedy. © 2022 Shawn Levy. Used with permission of the publisher, Doubleday Books.

Shawn Levy

Shawn Levy is the former film critic of The Oregonian and KGW-TV. His writing has appeared in Sight and Sound, Film Comment, American Film, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, The Hollywood Reporter, and The Black Rock Beacon. He is the bestselling author of Rat Pack Confidential, Paul Newman: A Life, and Dolce Vita Confidential. He jumps and claps, and sings for victory in Portland, Oregon.