When an Umbrella is More Than Just an Umbrella

The Potent Symbolism of Brollies, from Mary Poppins to Harry Potter

One of the endearing features of Charles Dickens’s “umbrella work” is the number of uses to which he put his brollies.

They are rarely merely umbrellas but the signifiers of something else, whether through similarity, metaphor or context. In addition to a vast array of sexual clues and cues, John Bowen has found Dickensian brollies masquerading as “weapons and shields . . . birds, cabbages and leaves.” And whether they’re in the right place or the wrong place (like the umbrella in Quilp’s eulogy), there is some intangible but undeniable facet of umbrellaness that has captured the human imagination for centuries. Perhaps it is the awkward elegance of them—these beautiful objects that are useful for so little else, that break so pathetically, that are cumbersome and accident-prone whether discarded, spread or folded. Perhaps it is their potential to arrest us, visually. Even in 1855, when the colors available for umbrella canopies were fewer and less varied than ours today, William Sangster wrote joyfully of the wide, uncovered market-place of some quaint old German town during a heavy shower, when every industrial covers himself or herself with the aegis of a portable tent, and a bright array of brass ferrules and canopies of all conceivable hues . . . flash on the spectator’s vision.

In 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write (2014), American playwright Sarah Ruhl explores the use of umbrellas on stage and the visual satisfaction they afford the audience. She believes it is the umbrella’s metaphorical power that gives it a unique ability to bestow verisimilitude on the fictive universe of the set:

The illusion of being outside and being under the eternal sky is created by the real object. A metaphor of limitlessness is created by the very real limit of an actual umbrella indoors . . . The umbrella is real on stage, and the rain is a fiction . . . A real thing . . . creates a world of illusory things.

As with theatre, so too with cinema. Movies are riddled with umbrella shots crafted by cinematographers unable to resist their appeal. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) opens with an extended bird’s-eye view of rain spattering a pavement, umbrellas passing to and fro. An iconic shot from Singin’ in the Rain (1952) shows Gene Kelly swinging from a lamppost, the folded brolly in his hand joyfully disregarded. Audrey Hepburn holds a gorgeous parasol aloft at the races in My Fair Lady (1964). And so on. Even just limiting myself to the films I watched the week I drafted this, two brollies leap to mind: a stunning moment in Takeshi Kitano’s film Zatoichi (2003) where an overhead shot of a rain-splattered roof edge gives way to the flowering of a battered red rice paper umbrella from below; or in Alfonso Cuarón’s Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004), where, before a particularly stormy quidditch match, an umbrella tumbles high through the air like a clumsy leaf.

Maybe it is the sheer irreplaceability of the umbrella that appeals. For all our leaps in technological development over the past few decades, for all our smart fridges and driverless cars and washing machines that reorder detergent online for us before we run out, there is no virtual substitute for the brolly. As Charlie Connelly says, “You can’t download an app to replace the umbrella.” Just as the new-fangled brollies of the industrial age were an anachronism in Sangster’s “quaint old German town,” so too are today’s umbrellas, for the opposite reason: for all the fabrics and technologies available to us now, the basic appearance, function and design of the umbrella has changed very little in the past 150 years. And until their design is revolutionized, or some manner of keeping the rain off us without a portable roof is conceived of and mass-marketed, that doesn’t look likely to change any time soon.

Rain Room. Random International, Curve, Barbican Cenre, 2012-2013.

Rain Room. Random International, Curve, Barbican Cenre, 2012-2013. Photo by author

Whatever the reason for their enduring appeal, the imaginative possibilities of the brolly are not limited to art, theatre and the cinema: writers, too, have made full use of its shape and form throughout history. This chapter will be devoted to those instances of umbrellaness that transcend the umbrella’s everyday form and function: from boats to flying machines; from clubs to swords; from umbrellas that become human (almost) to humans who (almost) become umbrella.

In his essay “Umbrellas,” Dickens asks,

Would M. Garnerin have astonished the denizens of St. Pancras, by alighting among them in a parachute liberated from a balloon, half a century ago?—would he have had many imitators, successful and unsuccessful, at all sorts of Eagles and Rosemary Branches and Hippodromes?— and, lastly, would Madame Poitevin, the only real, genuine Europa of modern times, have dropped down from the clouds on an evening visit to Clapham Common?—would all these events have occurred if umbrellas had never been invented?

The answer is, very likely, no. Today’s parachutes are almost unrecognizable as umbrella-children, but in fact it was the sheer unmanageability of the umbrella in windy conditions that caught the imaginations of late-eighteenth-century aeronauts, and the object played a vital role in the development of the parachute. When William Sangster was writing Umbrellas and Their History, the design of the parachute commonly in use at the time was “nothing more or less than a huge Umbrella.”

That’s not to say that European brolly aficionados were the first to think of it; just as the Continent lagged sorely behind the rest of the world on umbrella uptake, so they did on the parachute. The Chinese Shih Chi, completed in 90 B.C.E., tells the story of Ku-Sou, who is trying to kill his son, Emperor Shun. Ku-Sou lures his son to a tower, then sets it alight; Shun escapes by tying several conical umbrella-hats together and leaping to safety. A late-17th-century Siamese monk amused the royal court by jumping from great heights with two umbrellas fixed to his belt. Word of this reached Joseph-Michel Montgolfier, who in 1779 pushed a sheep in a basket from a high tower. The sheep floated to the ground unharmed with the aid of a seven and a half foot parasol Montgolfier had fastened to the basket. In 1838 John Hampton went even further and constructed a parachute shaped like an umbrella 15 feet in diameter. He took it up to 9,000 feet and cut it—along with himself—loose. He landed safely after a 13-minute descent.

A more complete—and occasionally gruesome—record of parachute developments to 1855 may be found in William Sangster’s book, of which an entire chapter is devoted to the aeronautic advances inspired by umbrellas. I, however, will move on, pausing only to note the sweet serendipity of the relationship between the two— for, as Cynthia Barnett reminds us, that which umbrellas protect us from also takes parachute form:

We imagine that a raindrop falls in the same shape as a drop of water hanging from the faucet, with a pointed top and a fat, rounded bottom. That picture is upside down. In fact, raindrops fall from the clouds in the shape of tiny parachutes, their tops rounded because of air pressure from below.

It is a logical imaginative step from umbrellas-as-parachutes to umbrellas-as-flying-machines—a step most famously made by P. L. Travers in Mary Poppins. The 1964 movie may have featured Julie Andrews drifting down Cherry Tree Lane in its opening scenes, but the Banks children must wait until the very end of the first book before they witness the hidden powers of Poppins’s parrot-headed brolly—and a sad scene it is:

Down below, just outside the front door, stood Mary Poppins, dressed in her coat and hat, with her carpet bag in one hand and her umbrella in the other . . . She paused for a moment on the step and glanced back towards the front door. Then with a quick movement she opened the umbrella, though it was not raining, and thrust it over her head.

The wind, with a wild cry, slipped under the umbrella, pressing it upwards as though trying to force it out of Mary Poppins’ hand. But she held on tightly, and that, apparently, was what the wind wanted her to do, for presently it lifted the umbrella higher into the air and Mary Poppins from the ground. It carried her lightly so that her toes just grazed along the garden path. Then it lifted her over the front gate and swept her upwards towards the branches of the cherry trees in the Lane.

“She’s going, Jane, she’s going!” cried Michael, weeping . . .

Mary Poppins was in the upper air now, floating away over the cherry trees and the roofs of the houses, holding tightly to the umbrella with one hand and to the carpet bag with the other . . .

With their free hands Jane and Michael opened the window and made one last effort to stay Mary Poppins’ flight.

“Mary Poppins!” they cried. “Mary Poppins, come back!”

But she either did not hear or deliberately took no notice. For she went sailing on and on, up into the cloudy, whistling air, till at last she was wafted away over the hill and the children could see nothing but the trees bending and moaning under the wild west wind.

While umbrellas were suggesting parachutes to aeronauts, they were suggesting sails to mariners. An umbrella was incorporated into the prototype for the inflatable rubber life raft in 1844—along with a paddle, it was intended for propulsion and steering. In 1896 the “umbrella rig” was developed for use on sailing boats:

[T]he sail when spread had precisely the appearance of a large open umbrella, the mast of the boat forming the stick. Twice as much canvas could thus be carried as by any other form of rig, and the sail had no tendency to heel the boat over.

Evidently sail-making technology superseded the umbrella-form, for the umbrella rig has quietly disappeared into the annals of sailing history—although it is tempting to wonder if it wasn’t a predecessor to the modern-day spinnaker.

On the subject of mariners, it takes only the smallest step of the imagination to flip the brolly upside down and turn its surface area and water-resistant qualities to advantage in repelling water from below, rather than above. A small step for man, perhaps—but a giant leap for a Bear of Very Little Brain. In the story “In which Piglet is Entirely Surrounded by Water,” Winnie-the-Pooh and Christopher Robin receive a message in a bottle from Piglet, who is trapped in his house by rising floodwaters. They need a boat to rescue him, but Christopher Robin does not own a boat:

And then this Bear, Pooh Bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, F.O.P. (Friend of Piglet’s), R.C. (Rabbit’s Companion), P.D. (Pole Discoverer), E.C. and T.F. (Eeyore’s Comforter and Tail-finder) —in fact, Pooh himself—said something so clever that Christopher Robin could only look at him with mouth open and eyes staring, wondering if this was really the Bear of Very Little Brain whom he had known and loved so long.

“We might go in your umbrella,” said Pooh.

“?”

“We might go in your umbrella,” said Pooh. “??”

“We might go in your umbrella,” said Pooh.

“!!!!!!”

For suddenly Christopher Robin saw that they might. He opened his umbrella and put it point downwards in the water. It floated but wobbled. Pooh got in . . . “I shall call this boat The Brain of Pooh,” said Christopher Robin, and The Brain of Pooh set sail forthwith in a south-westerly direction, revolving gracefully.

These curious craft are not limited to children’s storybooks: In The Sunshade, the Glove, the Muff (1883), Octave Uzanne comments on sketches that may be found in albums of Japanese art, depicting some human being excited to a singular degree, with hair tossed by the wind, and haggard eye, floating at the will of the tumultuous waves on a Parasol turned upside down, to the handle of which he clings with the energy of despair.

Umbrellas also have a long (and violent) history of being used as weapons. One early adaptation was the umbrella sword stick—a brolly with a slim sword concealed in its post. Although illegal today, they were once enough in demand to appear on James Smith & Sons’s stained-glass windows—where they remain to this day.

Perhaps the most famous umbrella-related murder occurred, appropriately enough, in London. In 1978, Georgi Markov, a dissident writer from Bulgaria, was waiting for a bus by Waterloo Bridge when he felt a sharp pain in his leg. He looked behind him to see a man with an umbrella get into a car and drive away.

Within days Markov was dead, killed by a minute pellet of ricin injected into his leg by—detectives surmised—the tip of a modified umbrella. Although no arrests were made over his murder, it was thought to have been committed in connection with the Bulgarian secret police. Charlie Connelly notes that when the Bulgarian government fell in 1989, “a stock of umbrellas modified to fire tiny darts and pellets was found in the interior ministry building.”

Anyone more than passingly acquainted with DC’s Batman comics will be familiar with The Penguin, or Oswald Chesterfield Cobblepot, one of Batman’s long-term nemeses and wielder of an extravagant array of weaponized umbrellas—amongst them, the Bulgarian design used to murder Markov. The Penguin’s umbrellas include a vast range of modifications, limited only by the writer’s imagination: knives, swords, guns and poison gas all make regular appearances.

One completely novel approach to umbrellas as weapons is that taken by Rubeus Hagrid, whose umbrella is far more than it initially seems. Let’s return to that memorable scene on Mr Potter’s 11th birthday, when Hagrid tells Harry he’s a wizard and has been invited to study magic at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Uncle Vernon roundly insults not just Harry and his parents, but the headmaster of Hogwarts as well—an insult Hagrid does not take lightly:

He brought the umbrella swishing down through the air to point at Dudley—there was a flash of violet light, a sound like a firecracker, a sharp squeal and next second, Dudley was dancing on the spot with his hands clasped over his fat bottom, howling in pain. When he turned his back on them, Harry saw a curly pig’s tail poking through a hole in his trousers . . .

A magic umbrella? Not quite. The true state of affairs is revealed the next day when Hagrid takes Harry shopping for a wand at Ollivander’s:

“But I suppose they snapped [your wand] in half when you got expelled?” said Mr Ollivander, suddenly stern.

“Er—yes, they did, yes,” said Hagrid, shuffling his feet. “I’ve still got the pieces, though,” he added brightly.

“But you don’t use them?” said Mr Ollivander sharply.

“Oh, no, sir,” said Hagrid quickly. Harry noticed he gripped his pink umbrella very tightly as he spoke.

However, umbrellas can inflict quite enough damage without the aid of concealed swords, poison-pellet mechanisms or magic wands. A somewhat less infamous umbrella murder occurred in 1814, in what came to be known as the “Battle of the Umbrellas” in Milan. As Nigel Rogers reports in The Umbrella Unfurled (2013), following the collapse of Napoleon’s empire, Giuseppe Prina, a finance minister who had imposed severe taxes on the populace to meet the emperor’s demands, was dragged out of the Senate by an angry mob and clubbed to death with umbrellas.

Unfortunately for Prina it was probably not the swiftest of deaths, and it was undoubtedly painful—but still not as grotesque as this Yiddish curse of uncertain provenance, which contains the most visceral umbrella violence you’re ever likely to encounter: “May a strange death take him! May he swallow an umbrella and it should open in his belly!”

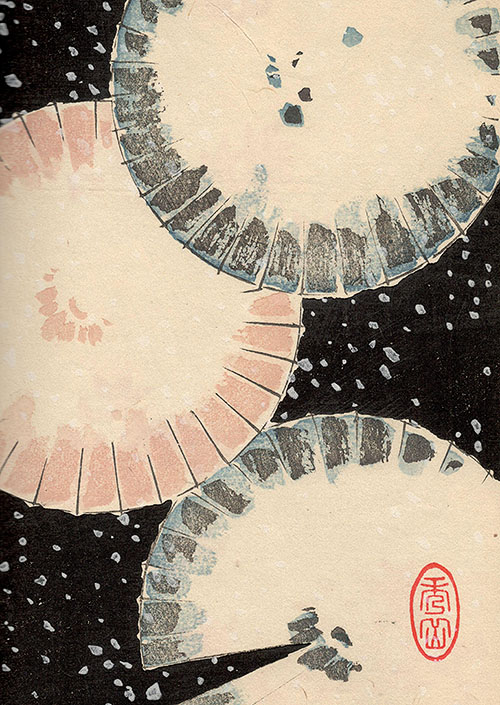

Bijutsu Kai [Ocean of Art], Vol. 1, 1904, woodblock print.

Bijutsu Kai [Ocean of Art], Vol. 1, 1904, woodblock print.

Courtesy Special Collections Division, Newark Public Library, Newark, NJ.A late-19th-century self-defense manual entitled Broad-Sword and Single-Stick contained an entire section on umbrellas. Echoing the sentiments of many a brollyphile indignant at the object’s poor standing in society, the author writes:

As a weapon of modern warfare this implement has not been given a fair place. It has, indeed, too often been spoken of with contempt and disdain, but there is no doubt that, even in the hands of a strong and angry old woman, a gamp of solid proportions may be the cause of much damage to the adversary.

The authors advise deploying the umbrella in two ways—as a fencing foil (light, parrying stabs with one hand), and a bayonet (firmly grasped and thrusted with two hands).

The mad woman in Elizabeth Is Missing seems rather to have gone for the “club” approach in this scene, when she chases a young Maud down the street:

. . . was holding the groceries against my chest, waiting for a tram to pass, when suddenly there was a great bang! on my shoulder. My heart jumped and my breath whistled in my throat. The end of the tram was trundling away at last, when bang! she hit me again. I leapt across the road. She followed. I ran up my street, dropping the tin of peaches in panic, and she chased me, shouting something I couldn’t catch . . . There was a bruise on my shoulder for weeks after that, dark against my pale skin. It was the same colour as the mad woman’s umbrella, as if it had left a piece of itself on me, a feather from a broken wing.

Just as Derrida has described the umbrella as both feminine and phallic, so too does it function as both weapon and defense. An open umbrella can act as a shield against not only rain and sun, but also bullets and other projectiles. At least two notable leaders have employed fortified umbrellas in their defense: Queen Victoria, who had a number of parasols lined with chain mail following an assassination attempt, and French president Nicolas Sarkozy, who in 2011 had a £10,000 Kevlar-coated umbrella made for his bodyguards in case of their needing to shield him. Apparently this umbrella was so strong that his bodyguards were able to smash tables with it.

Rather more outlandish is this anecdote from colonial India, related by William Sangster, in which an umbrella is put to an entirely novel defensive use:

The members of a comfortable picnic party were cosily assembled in some part of India, when an unbidden and most unwelcome guest made his appearance, in the shape of a huge Bengal tiger. Most persons would, naturally, have sought safety in flight, and not stayed to hob- and-nob with this denizen of the jungle; not so, however, thought a lady of the party, who, inspired by her innate courage, or the fear of losing her dinner—perhaps by both combined seized her Umbrella, and opened it suddenly in the face of the tiger as he stood wistfully gazing upon brown curry and foaming Allsop. The astonished brute turned tail and fled, and the lady saved her dinner.

And her life, presumably.

One umbrella, deployed in the fateful seconds before U.S. president John F. Kennedy was fatally shot on November 22, 1963, continues to intrigue conspiracy theorists to this day. Louie Steven Witt, dubbed the “Umbrella Man,” was captured on film holding an umbrella aloft moments before shots were fired at the president’s car. Josiah “Tink” Thompson—one of the first to spot the Umbrella Man in footage—included Witt and his umbrella in his 1967 book Six Seconds in Dallas: A Micro-Study of the Kennedy Assassination. Given that the shooting occurred on a bright, sunny day, and no one but Witt was carrying rain gear of any kind, sinister theories proliferated. One suggested that the umbrella was itself a weapon used to fire a disabling dart into Kennedy’s throat. Another held that the raising and lowering of Witt’s umbrella functioned as a signal to the shooter(s).

John Updike, reflecting on Thompson’s book in a December 1967 issue of The New Yorker, wrote:

[The Umbrella Man] dangles around history’s neck like a fetish . . . We wonder whether a genuine mystery is being concealed here or whether any similar scrutiny of a minute section of time and space would yield similar strangenesses—gaps, inconsistencies, warps, and bubbles in the surface of circumstance.

Despite the microanalytic nature of his own book, Thompson himself appears to agree with Updike: in Errol Morris’s 2011 short film Who Was the Umbrella Man? Thompson states that he accepts Witt’s own explanation, which he gave before the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978. Witt claimed that his black umbrella was raised as a protest, not at John F. Kennedy himself but his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, who in his role as U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom had supported Neville Chamberlain in his much-hated policies of appeasement towards Nazi Germany. Thompson says, “I read that and I thought, ‘This is just whacky enough it has to be true!’”

The iconicity of Chamberlain’s umbrella had no doubt faded somewhat by 1963—but from a purely brolliological perspective Witt’s explanation certainly checks out. However, hundreds of commenters on the video’s YouTube page beg to differ, and over 50 years later, Witt’s umbrella remains an object of speculation and intrigue.

On a lighter note, umbrellas also make rather handy hiding places—and not just for one’s own self. In Hergé’s Tintin book The Calculus Affair (1960), the absentminded professor Cuthbert Calculus develops a glass-shattering sonic invention that he fears could be turned into a weapon. Seeking advice, he heads for Switzerland to consult with a colleague but is abducted on the way. Tintin and Captain Haddock begin pursuit. On their hunt, they come across the professor’s signature umbrella, which Tintin’s dog, Snowy, takes responsibility for, carrying it around in his mouth. When they finally intercept Calculus the first thing he asks after is “My umbrella! My umbrella!”—before he is re-abducted and whisked away.

They lose his umbrella before rescuing him a final time, and there is a high-speed pursuit involving tanks and gunfire. Totally oblivious to Death flying about their ears, Calculus asks, “My umbrella! Have you got my umbrella?”—To which Captain Haddock expostulates, “Blistering barnacles, your umbrella! This is a fine time to worry about an umbrella!” However, the object is eventually recovered, prompting what is perhaps the most blissful human-umbrella reunion scene in literary history; Calculus clasps the object to his chest, crying, “My umbrella! My own little umbrella! At last I’ve found you!” All is explained when Calculus reveals that he had hidden the plans for his inventions inside the hollow handle of his brolly.

Hagrid’s wand and The Penguin (and possibly the Umbrella Man) aside, these are all fairly quotidian examples of brollies transcending their usual designated functions. Far more boundary-crossing are the imaginative uses to which they have been put by writers—or hallucinogens. In The Prime of Life (1960), the second volume of her memoirs, Simone de Beauvoir relates Jean-Paul Sartre’s first experiment with mescaline—an experience that, oddly enough, includes an umbrella or two:

Late that afternoon, as we had arranged, I telephoned Sainte-Anne’s, to hear Sartre telling me, in a thick, blurred voice, that my phone call had rescued him from a battle with several devil-fish, which he would almost certainly have lost . . . He had not exactly had hallucinations, but the objects he looked at changed their appearance in the most horrifying manner: umbrellas had become vultures, shoes turned into skeletons, and faces acquired monstrous characteristics, while behind him, just past the corner of his eye, swarmed crabs and polyps and grimacing Things.

Other monstrous associations crop up in Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent: firstly, when a young girl has a vision of the titular serpent as “a coiled snake unfolding wings like umbrellas,” and later when a very large and very dead sea creature washes up on the shore:

All along the spine the remnants of a single fin remained: protrusions rather like the spokes of an umbrella between which fragments of membrane, drying out in the easterly breeze, broke and scattered.

One extraordinarily transformative brolly may be found in G. H. Rodwell’s Memoirs of an Umbrella. As mentioned earlier, this umbrella so transcends its object status that it has become sentient and narrates a storyline of typically Victorian complexity from its (or rather, his: the umbrella is unambiguously gendered) vantage point as he is lost, loaned and forgotten, passed from character to character, “taken up here, or put down there, or dropped from a coach-box, or hung upon a peg.” As the umbrella himself points out, what better perspective could be gained but that of an umbrella?

Whether it be spread out cold, wet and weeping in the servants’ hall, or, dry and snug in the butler’s room; whether it be enviously watching over the heads of two happy lovers; or stuck almost upright, beneath the arm of the Honourable E. B—: still they are all situations for observing human nature.

It is a perspective that does not come cheap, according to this umbrella:

Talk of slavery! what can be more perfect than that of an Umbrella! At one moment our tyrant masters will raise us up to the skies; at the next, lower, nay, thrust us into the very mire! It is true we have . . . our moments of sunshine, but they are “few, and far-between”: perhaps, the fewer the better for our well-being, for bad weather suits us best. And that, which generally makes others low, causes the umbrella to be elevated.

We learn that, while entirely dependent on humans for carriage from place to place, this umbrella has emotions and hopes and desires of his own. He is frequently irritated by being removed from all the action—“I have generally been annoyed by being carried away exactly at the very moment I had wished to stay”—and at one point he wonders, “If a poor umbrella could feel this, what ought not real flesh and blood to have felt?” Although he cannot physically move, his emotional peaks come tantalizingly close, with descriptions like, “my very silk began to tremble” and, “the name vibrated through my whalebones.” Above all—for all the talk of slavery—he delights in being useful:

We had scarcely reached the New Road when it began to rain, not much, certainly, but enough to raise me considerably in my own estimation . . . The rain ceasing as suddenly as it had commenced, I was lowered, and felt myself no longer of any consequence.

Memoirs of an Umbrella: the narrator.

Memoirs of an Umbrella: the narrator. Illustration by Landells, from designs by Phiz.

The central conceit of Memoirs of an Umbrella is ridiculous by most standards, and it is a tribute to the author that the final work is sufficiently compelling to draw a reader—well, this reader, at any rate—through to the final pages. That said, sentience in brollies is not limited to out-of-print 19th-century fiction, or kasaobake. The Japanese poet Yosa Buson penned a haiku in which the sentience of two inanimate objects forms the final, delightful twist:

The spring rain—

telling stories to each other they pass by:

raincoat and umbrella.

English Poet Denise Riley, in her poem “Krasnoye Selo,” refers to umbrellas and their “carriers” going about their daily duties—a breathtaking reversal in which it is the umbrella that takes centre stage, the umbrella that possesses volition. The individuals beneath them factor in only as brolly-bearers, as enablers—not unlike the Greek and Egyptian slaves charged with holding umbrellas over the heads of their rulers.

Perhaps the most fascinating transcendence of all is that between human and brolly—one of which Will Self is a master. It is Audrey—symbolic throughout this book of the anxieties connected with the mechanical age—who undergoes this extraordinary transformation, not once but twice. The first time occurs just before her encephalitis permanently relapses, when, caught in a sudden gust of wind, Audrey’s arms:

fly up and away, struts jerkily unfolding from ribs, then bending back on themselves, so that the riveted pivots bend and pop . . . her stockings are half unrolled on her stiff posts, her handles in their worn leather boots rattle across a cellar grating . . .

Her temporary identification with the umbrella is prophetic, for Audrey will soon, like a broken brolly, be abandoned and all but forgotten as she succumbs to an illness no one can understand or treat, and is shut up in a psychiatric hospital for the rest of her life.

Will Self does not quite have a monopoly on human-umbrella confusions, however: the character of Miss Hare, in Patrick White’s 1961 novel Riders in the Chariot, undergoes a comparable, although much subtler, transformation of her own. Miss Hare, one of the four “visionaries” of the novel, is herself a creature of margins and transient boundaries: this passing comparison—introduced very early in the novel—is a most fitting introduction to the transcendent nature of her character:

Miss Hare continued to walk away from the post office, through a smell of moist nettles, under the pale disc of the sun. An early pearliness of light, a lambs’-wool of morning promised the millennium, yet, between the road and the shed in which the Godbolds lived, the burnt-out blackberry bushes, lolling and waiting in rusty coils, suggested that the enemy might not have withdrawn. As Miss Hare passed, several barbs of several strands attached themselves to the folds of her skirt, pulling on it, tight, tight, tighter, until she was all spread out behind, part woman, part umbrella.

__________________________________

From Brolliology: A History of the Umbrella in Life and Literature. Used with permission of Melville House. Copyright © 2017 by Marion Rankine.

Marion Rankine

Marion Rankine is a London-based writer and bookseller. Her work has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, Overland, and For Books’ Sake, among other places.