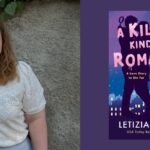

When a Lifelong Editor Becomes a Novelist

What I Learned on the Other Side of the Desk

After 30 years as editor and publisher, I found myself on the other side of my professional process—as writer this time—and learned a valuable lesson: I suck at editing myself. The thousands of hours I’d spent editing others did little to hone that skill to improve my own work. I sucked at the very thing I’d built my career on.

Over the years, I’d drag out a novel in progress, or memoir, or toil away at any number of essays, only to file them away again, frustrated and unsatisfied, yet hopeful that I would return to them someday. The thought of asking for help never occurred to me. You could say that this shows an embarrassing lack of courage on my part. In the same way that we can identify fissures in the character of others but not in ourselves, the unexamined on the page often remains invisible until someone else points it out. But you have to share the page in order for that to happen. It is in the sharing where the work gets done, and it takes courage to share.

In my early years as an editor, editing seemed to me an act of audacity. To question a writer’s intent or to suggest ways to improve upon what was already on the page seemed the ultimate arrogance. Over the years, those youthful feelings of audacity turned into a sense of responsibility and an appreciation for the intellectual puzzle editing presents. I was drawn to the close reading editing demands and I became adept at folding myself into the skin of a writer. The task is both monastic and intimate—we edit in silence in order to listen to the voice of the writer—and the skilled editor must suspend not only ego, but inner voice as well, to make room for another’s. There is a fine balance to be struck where humility must sit comfortably alongside a critical eye and ear in order to accomplish the task at hand.

I recently edited a memoir in which something unwritten seemed to burden the story. At the end of the manuscript, I still didn’t understand the main character’s central dilemma. The writer is known and respected for the lucidity of her storytelling, and yet I couldn’t put my finger on what was not there. After hours of discussion, I learned that a big piece of the story was missing because it concerned the abuse of a woman by her husband over the course of 20 years, something suffered in private and spoken about in confidence to the writer. The story was never told because there were children to protect, defamation claims to be avoided, a potentially dangerous man to mollify, even if only by omission.

“Editing is both monastic and intimate—we edit in silence in order to listen to the voice of the writer—and the skilled editor must suspend not only ego, but inner voice as well, to make room for another’s.”

As an editor, I encounter these kinds of omissions all the time. The story behind the story always tells the most truth. Anyone in the business of storytelling encounters tough decisions about what to say and what to leave out. It is the editor’s job to help the writer find a way closest to truth—whatever that may be—while protecting herself or others. Each writer relies on her own compass for these things, and with the help of an editor, together they wade through the muck of life and meaning, writing and carefully crafted prose.

*

I’d written a novel 15 years ago in a fever pitch when my sons were babies and I had a lot to say about motherhood and career building. I was struggling and confused and hoped that my characters would become a kind of Greek chorus of wisdom. Clearly, I didn’t do a good enough job because when my agent sent the novel out on submission, 30 publishers turned it down.

I was an editor, so I knew why. The hardest thing for a writer to do is to write a book that people want to read. We ask a lot of people to spend their time and money to read our stories. The book must earn the right to both. And even when it does, it doesn’t always find its audience, at least not immediately. I am unsentimental about it because decades of publishing have inured me to the fact that no one knows if a book will find its readers. There’s a lot of hope built into the whole process. Luck has something to do with it, timing is key, and getting it right on the page is imperative.

While there were aspects of my book that worked—the characters were compelling, if not entirely believable, and the storylines unique—my execution just wasn’t up to par. I knew it, but I couldn’t figure out how to fix it myself and at that point there wasn’t a willing editor to get in the muck with me. The book went back in the drawer.

When I had the good fortune of seeing part of my novel turned into a feature film (Maggie’s Plan, directed by the luminescent Rebecca Miller) there was pressure from some to consider the novel for publication. I reluctantly showed a few editors and good fortune struck twice. An offer came from a publisher, with the caveat that I would work like hell with a tenacious editor to make my book publishable.

My editor had the audacity to challenge not only my language (admittedly and shamefully lazy in many instances) but my intention as well. I marveled at the confidence, fierceness, and tenderness with which she directed her commentary and corrections. She challenged my point of view. She re-cast sentences, making them cleaner, lovelier, more directed. She patiently did this over the course of four iterations of the novel. It could be jarring, these impositions on my writing, and yet they were welcome: I felt grateful for every correction, line cut, re-write and query. My editor saw things about my characters and story that were hidden from me, as if she had a key to the door of a dark cellar—one I’d kept locked for fear what I’d find down there. She flipped the switch for the light and led the way down those shaky stairs. I trusted her guidance, but I kept asking myself: how could she care enough to pay this much attention to someone else’s writing?

“Only by being on the receiving end of the editing process could I see editing as an act of generosity and love.”

Through all of the time spent with other writers’ words, in the editing process and as I went about my day, listening to them in order to better extract meaning from their work, I never understood how they became part of the fabric of my life. What did I think I was doing all those years? Sure, it was a job I was paid to do—but the fallacy of being a book editor is that you spend your day at the office reading and editing, when in fact that part only gets done outside of the job—in the evenings, on weekends, sometimes while on vacation. Office hours are spent at meetings and doing the work of production, planning, acquisition, marketing, and publicity.

Only by being on the receiving end of the editing process could I see editing as an act of generosity and love. For decades, I understood this exchange from one direction, but now I was granted the gift of being able to see the editorial process as a kind of “mutual reflection,” as one of my friends, the writer Rozanne Gold calls it.

So an editor must know a writer better than she knows herself, or at the very least she needs to ask the right questions. And an author must have the courage and humility to answer those questions. This reminds me of an editing session for my very first book as a young editor, written by artist David Wojnarowicz. He asked me, not unkindly, “Are you my editor or my fucking shrink?” I’d be accused of the same many times over my career. Now, as a writer, I know exactly what he meant.

This writing and book business is a conversation, between a writer and herself, between an editor and a writer, and ultimately between the writer and her reader. It is this connection that counts, this mutual reflection that is ultimately about something we all could use more of: generosity and love. I had to sit humbly on the other side of the desk to understand what I’d spent the better part of my adulthood doing.

Karen Rinaldi

Karen Rinaldi is the publisher of Harper Wave, an imprint she founded in 2012, and a senior vice president at HarperCollins Publishers. While she has worked in the publishing industry for more than two decades as a publisher, editor, and content creator, this is her first time in the role of novelist. The End of Men inspired the story for the 2016 film Maggie’s Plan.