Whatever Ideas About Writing You Have It’s Really Just Something You Do (Or Don’t)

Colin Barrett on the Importance Letting His Characters Talk a Little Shite

When I’m writing, I don’t often get ideas, and I don’t like it when I do. Ideas about writing that is. I have ideas about the characters and the plot of my stories all the time of course, but I like to think of these as very practical ones, utilitarian and contingent, relevant only until they solve a problem, whereupon they, like the problem, disappear, or at least I hope so.

It’s the other ideas I don’t like. The capital “I” ones, about capital A art and capital W writing and all that. Any inclination, tendency or notion that, if you give it more deference than it merits, might calcify into a prescription.

It’s not that I don’t like capital I ideas. They just get in the way of the writing.

You can have any number of ideas about writing, but in the end, writing is something you do.

Nonetheless, I do get ideas, and the ones that persist, the way a low-level headache persists, as a languishing pressure or obtrusion, discernible but usually of insufficient intensity to motivate me into raiding the medicine cabinet to deal with it. Not so obtrusive, in other words, that I can’t get my writing done.

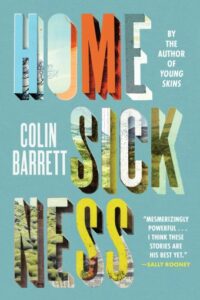

I did succumb to a few ideas during the writing of my new collection of stories, Homesickness. It’s my second collection, my second straight book. Eight stories, six set in the west of Ireland, rural county of Mayo where I grew up. There’s one set in a city I don’t think I bothered to explicitly name, but which is Dublin, and one set in Toronto, which I do take care to name.

Talk enough where I am from and you will be labeled a bullshitter. A shite-talker.

These ideas—about writing towards, rather than from inside, your characters; about the agility, fairness, and sheer sophistication of homely old third person, past tense narration as compared to the alternatives; about stories as a social rather than an introspective form—maybe in the moment some of these ideas even felt profound, but what matters is that they did not get in the way. I got the book done, and now they are gone.

The ideas I do care about are the ideas my characters have—about the world and everything else. The problem, for my characters, is that most of them are quite circumspect about those ideas, or, more accurate to say, that in the run of their lives they tend to be rarely afforded a stage on which they might be invited to offer up their ideas about the world.

So the only way for them to express their ideas is to stuff those ideas, or hints of those ideas, into their talk with other people. And talk with other people, at least where I’m from, is a wonderful, and tricky prospect, a ritual of sly deflection and ebullient undercutting and doting disabuse. Talk round my way is expected to be entertaining even at its most perfunctory or equivocal, and will, as a matter of course, be interspersed with those sudden pauses and patient silences for which the people I grew up among have an unnatural tolerance.

And while conversational fluency, the ability to navigate social intercourse, is prized there, like anywhere, it is prized only to a point. You can talk but you can’t say too much, can’t give too much of yourself away. Talk is circuition. Talk is going around the houses. Talk is just a way of killing time. Silence, no matter how unwelcome or bristling, is to be respected.

The logic goes something like this: if you are in position where you could say something, but you decline, it follows that you do so because you know that the thing you are declining to say must be of greater value withheld than disclosed. And whether you are in fact right or wrong, there’s an integrity to that.

Whereas garrulousness is the recourse of the know-nothing, or, more generously, the recourse of the person who delights in having nothing to say.

Talk enough where I am from and you will be labeled a bullshitter. A shite-talker.

‘’Don’t mind him, he’s talking shite.’’

Which translates to—he talks to much, too easily.

Which, as a criticism, has less to do with the substance of what you are talking about, than the performance of the talking itself, its voluminousness, its unimpededness, its flow.

Interiority, the nuances and gradations of the inner self, blah blah, that’s all well and fine, but how you really find, reveal, character is simply by getting them to talk. Then it’s like how it is for the rest of us, out here in the world. They can try to say as little as possible, as carefully as possible, but it all comes out. It’s written all over their face.

________________________________________________________

Colin Barrett’s Homesickness is available now via Grove.

Colin Barrett

Colin Barrett was born in 1982 and grew up in County Mayo. In 2009 he was awarded the Penguin Ireland Prize. Young Skins won the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, the Guardian First Book Award, and the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature. His work has been published in The New Yorker, A Public Space, Granta, and The Stinging Fly. In 2015, Barrett was named a National Book Foundation “5 Under 35.”