How Sylvia Sleigh’s Nude Male Portraits Subverted the Muse Narrative

The Feminist Painter Who Resisted Objectification

During the 1960s, feminist painter Sylvia Sleigh shocked the art world when she replaced visions of the female muse with hyper-realist portraits of naked male bodies: “I had noted from my childhood that there were always pictures of beautiful women but very few pictures of handsome men so I thought that it would be truly fair to paint handsome men for women.”

Turning the tables on art history, Sleigh substituted nude men for the reclining, undressed women traditionally seen in masterpieces by the likes of Peter Paul Rubens or Gustave Courbet. But who were these male muses and were they complicit in her feminist intervention which shocked the art world?

It was in 1943 that Sleigh met Lawrence Alloway at an evening art history class at the University of London. Aged twenty-seven, she was ten years older than the seventeen-year-old who was just beginning to make a name for himself, as a critic and curator of contemporary art. From the very start, the pair were emotionally and intellectually drawn to one another.

Sleigh soon started to use Alloway as a model for her paintings. An early work, At the Café (1950), shows the couple seated together at a train station café. There is a formality to the scene, in which Alloway wears a jacket and bow tie, and Sleigh a black dress, with white pearls and a hat. However, there is a knowing intimacy between them: their arms, leaning across the tabletop, touch and, as their hands disappear from view, it seems likely that they are secretly linked.

Sleigh painted this picture while she was still living in Sussex, and married but estranged from her first husband, Michael Greenwood. She later explained that the double portrait “commemorates the many times that I had to leave Lawrence and return to Pett . . . Many times when he took me to the station we went to a café while waiting for my train.”

As Sleigh’s first marriage deteriorated, her connection with Alloway developed from close friendship to romantic relationship. Following her eventual divorce from Greenwood in 1954, she married Alloway, within just months. In 1961, the couple emigrated to New York, where Alloway took up the role of senior curator at the Guggenheim Museum, looking after its great collection of modern art by Marc Chagall, Joan Miró and Piet Mondrian, amongst others.

Relocating to America was also the best thing that Sleigh could have done for her career. Arriving in New York, she encountered second-wave feminism, which was surging across the city. Having long felt the injustices of a patriarchal art world back home in Britain, Sleigh assumed a leading role in this active scene, where she found acceptance and purpose: “Feminism gave us this intense freedom of expression thus allowing a change. Anything that helps to express the artist’s ideas, whether it is to surprise, glorify, shock or simply express a philosophy will lead to a change or will simply allow an opportunity for change.”

During the mid-1960s, Sleigh’s feminist convictions began to infiltrate her paintings—of nude male figures. She depicted her models in domestic interiors, reclining on beautifully patterned sofas and chairs, or looking at themselves in the mirror. Sleigh was deliberately, and defiantly, taking on centuries of art history, in which women had been painted naked for men to gaze upon.

In museums around the world, you will find celebrated masterpieces in which men are clothed but women’s bodies are exposed. Black and Indigenous women are often objectified, fetishized as an exotic “other” to fulfil unspoken fantasies of the male viewer; on the other hand, white women are frequently depicted as sexualized and desired; their pale skin instead depicted as inviting the touch of an artist.

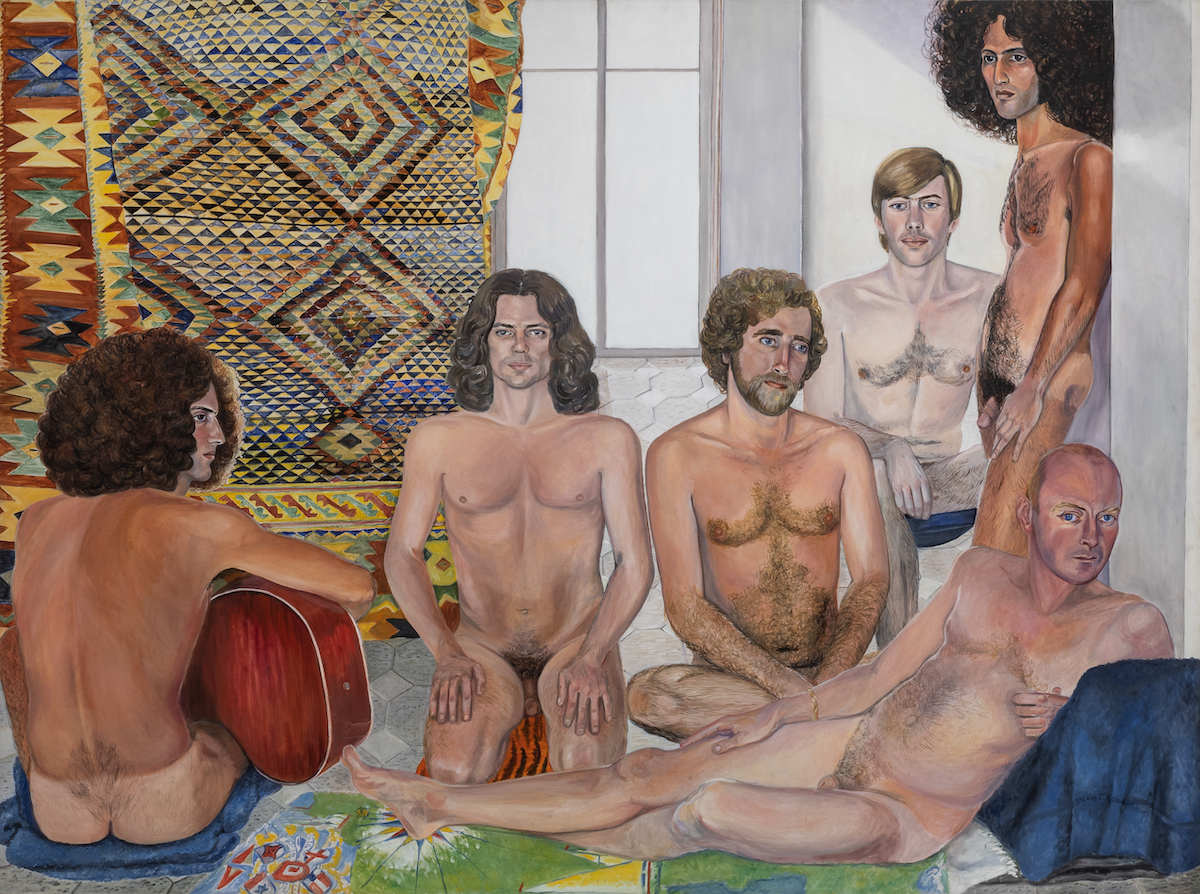

Sylvia Sleigh, “The Turkish Bath,” 1973, Oil on canvas, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Purchase, Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions, 2000.104. Photograph ©2022 courtesy of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago.

Sylvia Sleigh, “The Turkish Bath,” 1973, Oil on canvas, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Purchase, Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions, 2000.104. Photograph ©2022 courtesy of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago.

Diego Velázquez’s famed Rokeby Venus (1647–51) pictures the Roman goddess of love, reclining nude on a bed. Her son Cupid holds up a mirror in which she admires her sensual reflection. Across the frame of this mirror are draped pink ribbons, alluding to the fetters which Cupid would use to bind lovers together, and serving to enhance the erotic atmosphere of the painting.

Many art historians have now critiqued the ways in which male artists painted women to be looked upon as objects of desire. As the art critic John Berger wrote in his seminal book Ways of Seeing in 1972, “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘Vanity,’ thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.”

Then in 1975 Laura Mulvey, a feminist film theorist, coined the term “the male gaze.” In a ground-breaking essay titled “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” she argued that traditional Hollywood films represent women as sexual objects, positioned for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer. As Mulvey wrote, women are characterized by their “to-be-looked-at-ness” and “spectacle,” while man is “the bearer of the look.”

Even before the arrival of these theories and texts, however, Sleigh made a significant first step in calling out the sexist objectification of women in art. Turning her female gaze on the male nude, she confronted portraiture’s gender imbalance. She deliberately reworked famous paintings by replacing naked women with male models: “It was very necessary to do this because women had often been painted as objects of desire in humiliating poses. I don’t mind the ‘desire’ part, it’s the ‘object’ that’s not very nice.”

However, Sleigh was adamant that she had no intention of humiliating or objectifying men: “In the ’60s I made a point of finding male models and I painted them as portraits, not as sex objects, but sympathetically as intelligent and admired people, not as women had so often been depicted as unindividuated houris.”

Sleigh’s models were close friends—artists, writers and musicians—who both she and her husband welcomed into their bohemian New York home. Rather than idealizing them, Sleigh captured the beauty of these men by including distinguishing features, from body hair to birth marks; at other times, she incorporated still-life objects, such as books or musical instruments, that pointed to her sitters’ unique personalities and talents. “I paint people whom I like or love . . . The human situation adds a certain poignancy to portraits.”

Among her most notable paintings is The Turkish Bath (1973). With this artwork, she reworked the erotic, 19th-century painting of the same title by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, in which he depicted a room filled with dozens of nude women who recline around a pool, their tangled limbs offering up an erotic fantasy for the male viewer.

Sleigh replaced Ingres’s anonymous crowd of female bathers with her more personal take on the subject. She pictured five of her close male friends: the musician, Paul Rosano, seen playing the guitar, the artist Scott Burton, and art critics John Perreault and Carter Ratcliff. This painting also includes Sleigh’s most important muse: reclining in the foreground, and looking directly at the viewer, is Alloway. What, then, did the critic make of these provocative paintings in which he starred?

Throughout their relationship, Sleigh and Alloway wrote heartfelt letters to one another. These highlight Alloway’s role in Sleigh’s creative life; among the repeated terms of endearment, she constantly addresses him as her muse: “Dearest Lawrence, thank you for your love, it is so important to me, you are my muse indeed; and I love you so well, dear love, adored poet. A golden vision of you always accompanies me; my Apollo. I love you, Sylvia.”

Given Sleigh’s gender-swapped paintings of the nude, it makes sense that she perceived of, and directly referred to, Alloway as her muse, reversing the stereotype of the female muse and male artist. Apollo was the Greek god of music and arts, and became a common term of endearment she continually used to reference the inspiration he provided for her.

Sleigh painted over fifty portraits of Alloway, who is characterized by his blonde hair, bright blue eyes and contemplative expression. In the painting Portrait of Lawrence Alloway (1965) Sleigh has caught her husband deep in thought, staring into the distance, while sitting on an iconic red Arne Jacobsen Egg chair. His grey shirt is casually unbuttoned to reveal his chest and a book lies besides him on the floor.

Sleigh also painted him naked on many occasions, lying in bed, or reclining on the sofa. However, far from reducing him to an object of desire, she was capturing intimate moments, in which he appears relaxed in their home. She frequently framed him with the background of their Chelsea town house, including modernist furniture and floral William Morris wallpaper, exhibiting the couple’s mutual interest in modern art and design.

Many of Alloway’s letters to Sleigh demonstrate their shared love of art: he would send his wife postcards of celebrated paintings from museums he visited and write detailed discussions on art history, drawing parallels to, and praising, his wife’s work. In more playful correspondence, Alloway included sketches of an alter ego, Dandylion, which he’d created. The half-human, half-lion cartoon is seen engaged in everyday tasks: reading, writing, sleeping and sunbathing. In a letter from 1950, Alloway notes how Dandylion’s “tail curled up with pleasure” while reading a note from Sleigh.

Behind the comic cartoons, Alloway was a deeply intelligent man. As a curator and critic, he favored contemporary art that pushed boundaries. Back in London, he had started his career at the forward-looking Institute of Contemporary Arts, serving as assistant director from 1955 to 1960. In New York, he became an advocate for abstract art and “pop art,” a famous term which he coined.

Sleigh’s feminist activism also positively influenced Alloway, who promoted women’s art across America. In 1977, he called out the “3-to-1 advantage” of men over women in the Whitney Annual, becoming the first male critic to publicly endorse the claims made by female artists; then, in 1979, he wrote the notable article ‘Women’s Art and the Failure of Art Criticism’ in 1979.

Although Alloway supported female artists, he never wrote publicly about, or directly promoted, Sleigh’s paintings. One reason for this, certainly, is that he would have been considered biased—we only have to look at his letters to see his overwhelming praise of Sleigh’s style. However, perhaps Alloway also recognized the importance of staying silent.

Steeped in a knowledge of art history, Alloway understood the significance of Sleigh’s gender-swapped paintings and his seminal role within them. Alloway also surely realized that he could allow her the most power by posing, compliantly, as her naked male subject. By taking on the role of muse, not critic, he was actively supporting her subversive paintings and feminist statement. His silence also ensured that Sleigh, not he, was given the spotlight. It was not his place to say what she had so eloquently stated in her paintings.

If we return to Alloway’s inclusion in The Turkish Bath, we can see him posed prominently in the foreground: he looks outwards, not only at the viewer, but also at the artist painting him into history. Alloway fully understood the importance of these images; held within this glance is his support, endorsement and validation for what Sleigh was doing—taking on centuries of sexist paintings. Fully committing to the role of muse, Alloway was legitimizing his wife’s work, and transferring all power to her in a true act of allyship.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces by Ruth Millington, available via Pegasus Books.