What Would Marcel Proust’s Instagram Grid Look Like?

Meredith Westgate Wonders About the Role of Memory in the Age of Social Media

When I look back at those early pandemic months, and even more recent ones, I feel a disconnect between how they appear online—walks outside! a cute tie-dye mask! my dog!—and what they felt like—unbearable. Full of fear, loneliness, uncertainty, frustration.

Much of what I saw then felt like one trending activity replacing another, a willed collective distraction and denial unfolding in photographs. Freshly baked banana bread cooling on the counter. Leftover scallions sprouting in a glass of water, catching the afternoon light. An attempt at sourdough. Tie-dying everything. Another failed sourdough.

Perhaps there was a purpose to this connection, a comfort in presenting the thing that we didn’t have — clarity. After all, a photograph presents stability in the most basic way that it cannot change. Even if once you finally dug into your banana bread, it caved into a gooey under-baked mess, the photograph always shows something appetizing, full of promise.

My dog, Olive, has since died, and my now-husband and I—married just the two of us shortly after she passed, in California—have moved across the country. The photos I posted in the early months now strike me as wistful. We were so lucky to be in our place, together with Olive. I remember nothing now of the stress and sadness of that moment, too; my memory has evolved, reshaped itself to see it so. The photos have stayed the same.

*

Thomas Bernhard wrote his biting, satirical novel, Extinction, in 1986, well before social media, or the Internet as we know it, but parts of it seem to speak directly to the Instagram age.

The good-looking person in a photograph is invariably the ugliest, the happy one invariably the unhappiest. They have photographs taken of themselves and hang them on their walls as representations of a happy and beautiful world, though in reality it is the unhappiest, ugliest, and falsest of all worlds. All their lives they stare at the happy pictures on their walls and are gratified by them, though they ought to be appalled.

Perhaps this was always the arc of personal photography, and only “the wall” has changed. Even then, Bernhard witnessed the curation of a secondary reality via photographs, the insistence and obsession of appearances, and the discrepancies of a life lived between both.

Today, a day or an event might be a bust—rushed, rained out, fraught with tension—and yet if one captures a moment that looks nice, even for a second, they can share it, as if it was. And perhaps, remember it that way, too.

I wonder why it is that when people have themselves photographed they always want to look happy, or at any rate less unhappy than they are,” Bernhard writes. “They take refuge in the photograph, they deliberately shrink into the photograph, which produces a totally false image, showing them as happy and good-looking, or at least not as ugly and unhappy as they are. What they demand of the photograph is an ideal image of themselves, and they will agree to anything that produces this ideal image, even the most dreadful distortion. It never strikes them how appallingly they compromise themselves.

It’s hard to read Bernhard’s words now without immediately thinking of face filters. The curation of self, the human desire to control one’s own narrative, didn’t originate with social media. The difference is that now our cameras are always with us, and everyone can have a platform for their curation, leaving a record that one day might even confuse themselves.

Imagine Proust in our current reality. He who dunked his petite madeleine and was immediately transported to his childhood memories. Today, would Marcel, the narrator, have paused—amid this revelation—to document the madeleine mid-dunk, to capture the perfectly arranged tea saucer? Would he take another bite and extrapolate on the profound moment via Instagram Live for his followers, Mme. De Villeparisis, Charles Swann, and Gilberte? Would he tag the location, Combray, for where it took him, emotionally?

And if Proust himself would join Instagram, how would he share? Would he post every object and place that holds meaning for him, regardless of whether anyone would understand? Would he overshare, with endless stories and posts, lengthy captions continued in multiple comments? Or would he only keep one photo on his grid, each time deleting the last, to protest this stagnation of true involuntary memory?

Would he, consumed with the staging of each moment, never have gotten to the involuntary memory at all, never found his link to an immersive escape into the memories that shaped him?

*

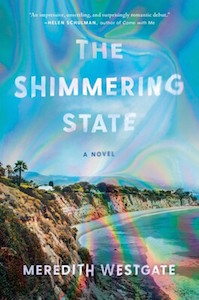

In my novel, The Shimmering State, one of the main characters, Lucien, is a photographer grappling with the death of his mother, unable to continue his artistic practice because there’s nothing he wants to see. Everything in his world is tinged with grief, with the absence of her.

Working on the book’s final revisions throughout the past year felt uncanny at times. In many ways, it is a book about grief and pain, about the unbearable desire to escape, even if it means being someone else. Here we were—faced with realities we didn’t know, a desire for escape we couldn’t have. Eventually, I found myself grieving the loss of my longest companion, leaving the quirky yet magical rental in Los Angeles that had truly become home for my husband and me, and with any larger sense of reality destabilized across the world.

My photographs around Olive’s passing last summer don’t reflect what I know it to have been; I see reality only in the absences. The weeks with nothing posted, when nothing felt worth capturing. I see it in the dead-end of that personal account, previously made up mostly of her presence.

Even now, one year later, as I’m beginning to feel the edges around her absence soften, my phone will remind me, “on this day, december 27, 2009” or “best of 2018,” and I will be confronted with the disconnect of my loss, greeting me as joy.

Memory protects us by allowing us to move on. Our memory of any moment is constantly evolving, for any memory is a memory of a memory. Inevitably, our memories change to suit our narrative about ourselves, set within a world of others. Trauma or anxiety can result in a compulsive return to an event or scenario in an attempt to solve it or protect oneself, even if that is what’s now causing the harm. This repetition, this resistance to healing, is precisely what modern technology enables, and often impresses upon us. To revisit a “memory” at any moment, to “remember” it in an interruption, without warning, exactly as you once chose to capture it, to curate it, to caption it.

Whether or not Proust would join Instagram, he would undoubtedly understand the tragedy of it.

What do we make of Joan Didion’s famous line from her essay, “On Keeping A Notebook,” that “we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be,” when we are now confronted with the selves we are presenting and curating every day? Instead, we risk never getting far enough to lose track enough to truly grow or change in a way that doesn’t feel intentional or affected.

In “Why I Write,” Didion describes what inspires her writing as “images that shimmer around the edges.” These images come from moments spent watching and waiting, and the “shimmer” in some ways is what memory adds, and what a photograph or Instagram post lacks. It implies a looseness that can change, and warp, given enough time and imagination. The imperfections in memory are spaces that lead to a lived-in meaning that can grow, finding its significance.

What moves me about photos of Olive throughout the years now is how, even then, I was grasping at moments, trying to hold time even as it passed. But it’s only walking in our old neighborhood back in New York, the leaves freckling shadows across the cobblestone street, that I’m Proust holding the madeleine to his lips. Only there where it feels as if Olive is still around, and as if I will soon be on my way to meet friends who have since moved.

Whether or not Proust would join Instagram, he would undoubtedly understand the tragedy of it, and how during our pandemic year(s) we have been more drawn into social media, more desperate to connect, and finding ourselves lonelier for it.

“Even the very simple act that we call ‘seeing a person we know’ is in part an intellectual one,” Proust wrote in Swann’s Way. “We fill the physical appearance of the individual we see with all the notions we have about him, and of the total picture that we form for ourselves, these notions certainly occupy the greater part.”

The act of curating one’s social media to connect with others is futile, as they will inevitably fill the spaces as they choose, based on their own selves, their own lens. What they see will hardly resemble what someone meant to show at all. What is Instagram, besides infinite space behind a shallow facade—most of the work of misunderstanding, already done for us.

In The Shimmering State, a new treatment has been developed using Memoroxin, a pill that can capture and deliver memories culled from a patient’s mind; if taken recreationally, one can escape the present altogether. Taken illegally, one can experience the high of another’s consciousness, a moment outside yourself. No more of social media’s glossing of memories, no more surface interactions. Another’s Mem would hold their actual experience, complete with their consciousness. It would allow for the deepest understanding.

And wouldn’t it be fascinating to see—to be—an artist working on their masterpiece, to feel the self-criticism, the uncertainty, or alternately, the lack of all thought accompanying their process? Imagine looking at “De Style, 1993” just having finished it? Or feeling the rush inside a musician, right before they go on stage? How about someone who appears to have everything, yet who thinks of the one person who doesn’t see them, in even the highest of highs?

Could we hate one another, as so many seem to today, with this kind of access?

This is human experience, not a snapshot that can be shared or captioned. Memoroxin, though flawed, has always struck me as hopeful—towards empathy, understanding—if only it weren’t also potentially damning to see yourself, or the world you know, through the eyes of another.

___________________________________________________

Meredith Westgate’s The Shimmering State is available now via Atria Books.

Meredith Westgate

Meredith Westgate grew up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and now lives in Brooklyn, New York. She is a graduate of Dartmouth College and holds an MFA in fiction from The New School. The Shimmering State is her first novel. Visit her at MeredithWestgate.com and on Instagram @MeredithWestgate.