What Was the Writers’ Room Like for The Sopranos?

Steve Schirripa, Michael Imperioli, and Writer Terry Winter Talk About the Iconic Show

One of the incredible writers on The Sopranos was Terry Winter. Among the twenty-five episodes he wrote were some of my favorites. As we said, he wrote “Pine Barrens,” which was a huge fan favorite. He wound up winning two Emmys for writing, and two more as an executive producer of the show. (We should probably take a second to explain, since a lot of people ask us all the time: writers would usually be the “producer on set” and work with the director to help make sure the script was shot as intended.

At some point, some of their titles would be elevated to “executive producer” or “co-executive producer” as kind of an indication of seniority. So when you see a writer with those titles, it’s kind of like they’ve become a made man in the writers’ room.) He also was one of the creators of Boardwalk Empire and Vinyl, and wrote The Wolf of Wall Street for Scorsese. An amazingly talented guy. And funny as the day is long.

–Steve Schirripa

*

Steve: You started out as an attorney, but somehow you morphed into this incredible executive producer and writer. How’d that happen?

Terry: I grew up in Brooklyn, it was a very blue-collar area. The idea of being a TV writer or a screenwriter was just so off my radar. If I would’ve told my friends, “I want to be a screenwriter,” they would’ve beat the shit out of me. They would’ve thrown me in the creek, in Gerritsen Beach. It sounded so ridiculous. Anyway, I’d push back those fleeting thoughts I had about it. I wanted to make money, and the two jobs I knew that made money were doctor and lawyer. So I ended up going to law school. Slogged my way through.

Finally I got a job in a big Manhattan firm and literally within two days, I realized I had made a grave, grave error. It just wasn’t me. I finally got to the point where I said, “All right, forget about the money and the diploma written in Latin and everything else. What do you want to do when you wake up in the morning?” The deep dark secret was, I wanted to be a writer.

Like everybody I knew, I watched a billion hours of TV as a kid. Abbott and Costello, The Honeymooners, the Bowery Boys, and all the classic Warner Bros. gangster films. Plus, I worked in a neighborhood where I rubbed elbows with a lot of guys, including Tony Sirico, in real life, who at that time was known as Junior Sirico.

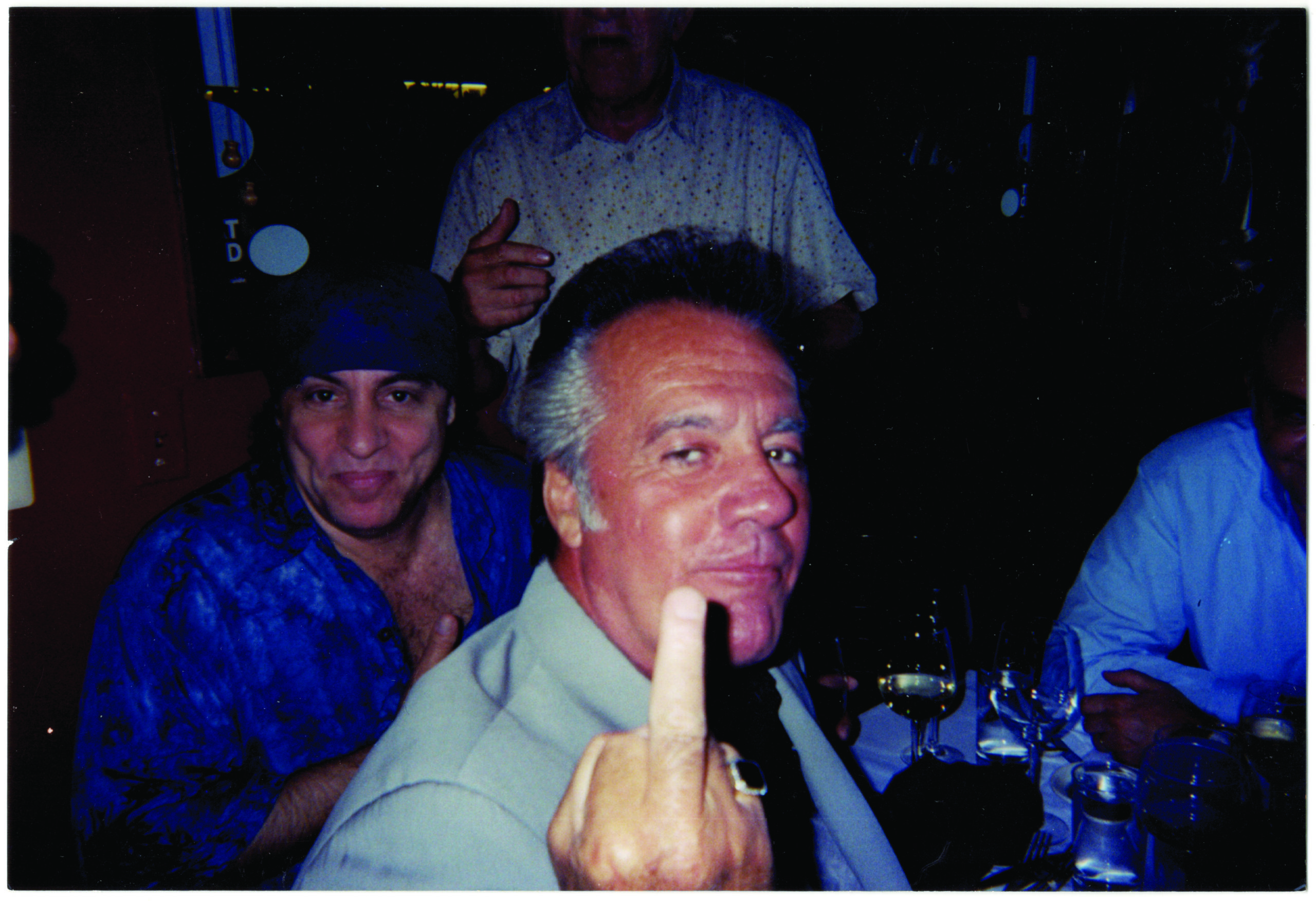

Tony Sirico greets me in his own inimitable way at a surprise party for my birthday at Ciel Rouge, a bar my wife and I owned in Chelsea when the show began. The Ciel Rouge parties were infamous: Sometimes we’d lock the doors at 4:00 a.m. and party on ’til dawn. –Michael (Courtesy of Michael Imperioli)

Tony Sirico greets me in his own inimitable way at a surprise party for my birthday at Ciel Rouge, a bar my wife and I owned in Chelsea when the show began. The Ciel Rouge parties were infamous: Sometimes we’d lock the doors at 4:00 a.m. and party on ’til dawn. –Michael (Courtesy of Michael Imperioli)

Steve: You knew him?

Terry: I knew of him. I actually worked in a butcher shop owned by Paul Castellano. I also worked at a card game run by Roy DeMeo, which if you read the book Murder Machine, that’s the DeMeo crew. That was my neighborhood. I was never involved with any of these guys, but the osmosis of how they thought, how they talked, how they acted, it seeped into me.

Steve: You go to law school, you get the degree, you’re at a big law firm, and you just pack up and move to L.A.?

Terry: Showed up like a country bumpkin, did not know anything. Rented a car and checked into this fleabag hotel on MacArthur Park. I took a job as a paralegal. I actually took my law degree off my résumé because I just wanted a nine-to-five job and people would see my law degree and say I was overqualified. I got a job at Unocal, the oil company, where they didn’t know I was actually a lawyer. I was home by five thirty and I started writing sitcom specs.

Michael Imperioli: For those who don’t know, in this case a spec is a sample script of an existing TV show. You use it kind of as an audition. The spec scripts that you wrote, Terry, were they original, or were they scripts for shows that already existed?

Terry: Generally the wisdom is, or was at least, that you needed to write for shows that were on the air. I ended up writing a Doogie Howser script, a Frasier, Mad About You, Seinfeld, Cheers, Home Improvement.

Steve: And these weren’t getting produced or anything, you were just doing this to basically learn to write?

Terry: I always make this analogy: it’s like kids who grow up and they want to be engineers, they take radios apart and put them back together again. I did that with stories. I would take six or eight episodes of Home Improvement, watch what happened, write down each scene, and I have a blueprint. I’d go, “Oh, okay, this is how they tell a Home Improvement story. There’s a cold open, in the first scene the problem is introduced, the problem gets exacerbated right before the commercial. You come back from the commercial, he talks to the guy over the backyard fence, gets some advice, then uses that advice to solve the problem. That’s a Home Improvement blueprint.”

Steve: So did you get an agent?

Terry: The Hollywood conundrum is, okay, you got to get an agent. You can’t get a job without an agent and you can’t get an agent without a job, so how the fuck does anybody ever do anything? It’s like nobody knows.

Steve: So what did you do?

Terry: I created a phony agency. First, I called a million agents and I couldn’t get anybody. In frustration, I went down to the Writers Guild and they happened to have a list of agents who would take unsolicited scripts. And what happened was a complete stroke of luck. On this list is the name of a guy that sat five seats away from me during law school. The name’s Doug. I called Doug, who I haven’t spoken to in years. He’s a real estate agent in Long Island.

I said, “What are you doing? Are you an agent now?” He goes, “No, I’m a real estate lawyer, but I had a client who wrote a book on real estate and I used my fee to get bonded as an agent. I don’t know anything about being an agent.” I said, “Well, you sound perfect. You’re my agent now.” He goes, “What do you mean?” I say, “I’m in Hollywood. I’m trying to write. I need to send my scripts in from an agent, so you’re my guy.” I created an agency out here with a mailbox, a phone mail system, an address, a letterhead, and I paid for everything.

I took a day off from my paralegal job and I hit every sitcom in Los Angeles. Back in the day, you could do this. I’d pull up to the Warner Bros. lot with a baseball hat and go, “Yes, I’m the messenger from this agency. I got to drop off these scripts.” A couple of weeks in, I get a call from the executive producer of Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. It’s a woman named Winifred Hervey Stallworth. She calls the “agency.” She says, “Hey, Doug. It’s Winifred Hervey, I read Terry Winter’s scripts. I think he’s really talented. We might like to have him in to pitch.” I call Doug in New York and it’s Friday and it’s already late, he’s gone for the day. I say, “Shit, I got to wait until Monday now.” Then I thought, “You know, he doesn’t know anything about being an agent. I’ll just call and say I’m him.” I call her up and go, “Hi, it’s Doug. I’m the agent.” I have no idea what agents say or do. I just wing it. She says, “Oh yes, Terry’s so talented.” I go, “Oh, he’s the most talented writer I’ve ever read. That’s for sure.”

Michael: So that’s how you get your foot in the door. Amazing. That’s a good lesson for people who want to know how writers get started in Hollywood. Look at how far you went. Look at the sacrifice. That’s what it takes. So what happened next? You started writing, and you met Frank Renzulli at a writers’ workshop?

Terry: Yes, Frankie, of course, is one of the great writers and hands-down one of the funniest people, easily. Literally, when you say somebody’s so funny they almost made you pee your pants, that’s Frankie. Just an incredibly funny guy. A couple years later, my agent sends me the pilot of The Sopranos. I call Frankie. Frankie says, “Yes, I’m meeting this guy, David Chase.” I said, “You got to get me in there.”

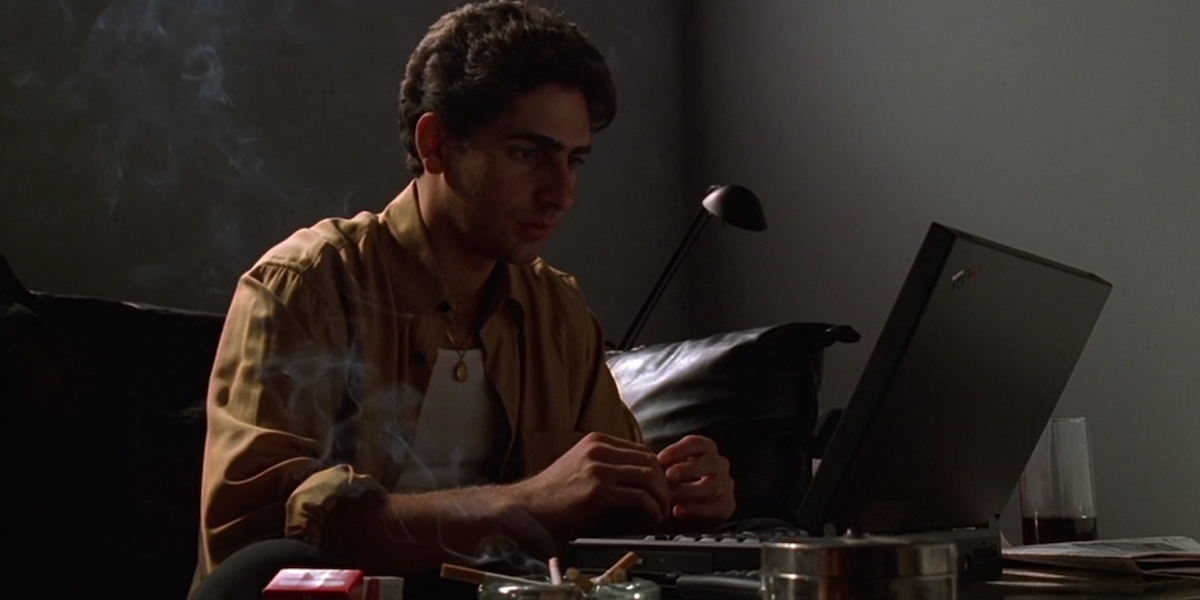

The first-season premiere party invitation for an unknown TV show, with the after-party held at a local pizza joint. (Courtesy of Michael Imperioli)

The first-season premiere party invitation for an unknown TV show, with the after-party held at a local pizza joint. (Courtesy of Michael Imperioli)

Michael: Now, you met David in Season Two, right? If I remember, only a few writers had been carried over from Season One, and the doors were open to some new writers.

Terry: The only ones who survived were Frankie, Robin Green, and Mitch Burgess. That’s it. The funny thing is, as Frankie was writing on Season One, he would tell me about the writers’ room and we’d riff and pitch. I pitched him stories and he pitched them to David. He’d write scenes and send them to me and I’d edit them. I’d add some lines. I was writing on the show a little, even though I wasn’t! In the meantime, I was writing what became my first feature, a movie called Brooklyn Rules. It’s a movie about me and my two best friends growing up in New York, it had some mob component stuff. I thought, “Oh, this would be a great sample for David.” David reads and hates it. I’m thinking, “Oh my God, really?” I thought I just shot myself in the foot.

But Season Two comes along and David’s ready to hire more people. Frankie said to David, “Look, I know you don’t like that script. You got to trust me on this guy. I know he can write the show.” David said, “All right, you’re vouching for the guy. I’ll meet him.”

Steve: So what was it like when you got to The Sopranos?

Terry: First thing, literally on day one, Tony Sirico comes up to me. The first thing he ever said to me was, “You’re the new writer. Let me tell you something. You ever write the script where I die, first I die, then you die.” I was like, “Okay.” He goes, “I’m telling you, don’t fucking think about killing me.” Every once in a while, we would type up a phony script page that had Paulie dying and leave it around. He got wise to that after a while.

Michael: Do you remember any story lines that never became scripts? Ideas that never made it to the show?

Terry: There were very few. I can maybe count on one hand the stories that didn’t go. I used to like to say that we used even our scraps of story ideas; we ended up making soup out of everything. We had a storyboard on one of the walls in the writers’ room, where there were just notions that we wanted to remember. By the end, we had checked off almost every little obscure thing we wanted to get to, like “Bear in New Jersey.” Boom! That was a whole episode. Just things we wanted to do.

There was one episode during the sequence of episodes where Tony was in the hospital, where we wanted to do a script about the privilege of rich people in hospitals, that at a fancy hospital in New York, there’s a floor that the average person doesn’t know about, but if you’re a celebrity or you’re a rich person, that’s where you go. There’s rooms where the family can stay, and Tony pulls some strings to get that special treatment. We might’ve actually had a script that was written. But by that point we just felt like we’d been in that hospital so long, let’s not do it.

There was another script that was about the home life of the female FBI agent, who was flipping Adriana. We got to spend time with her at home; maybe Tony had an affair with her or something like that. That never really got any traction. I had pitched an episode where a young kid breaks into Tony’s house and Tony is the only one there and he catches the kid and doesn’t know what to do. The idea was, the whole thing takes place entirely in the house, it’s just Tony and this kid. And he ends up killing him rather than let them go. Obviously, we never did that one either.

Michael, you were involved in a story line about a mentally ill guy outside the pork store?

Michael: Yes, who is obsessed with Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones producer. There was also one other one that we never did. I remember seeing it on the whiteboard—“A rat and nobody cares.” There was a rat who got out of prison and nobody gave a shit anymore. One of the guys says, “We got to get this guy,” but nobody cared at this point.

Terry: That’s the thing too. It sort of goes back to the Sammy Gravano thing. He’s out and he’s saying, “Okay, here’s my address, I’m in Arizona. If anybody wants to come get me, here I am.” You got to really have a very serious grudge to go to Arizona and confront that guy, so unless it’s very personal, what you’ll say is, “Oh, somebody should do that. Not me, I’m not getting involved.” The thing that people don’t realize is that it’s not even so much that you’re putting your own life in danger going to confront a rat or to bring honor to the family, it’s a murder rap. You don’t put yourself in a situation theoretically where you could get put away the rest of your life on a murder rap because you’re avenging some code of honor that doesn’t directly affect you. It’s not as casual as it seems in TV or in the movies. The whole gun-happy trigger-finger thing is not as accurate as we like to depict it in our business.

Michael: Very true. I have to say that I think The Sopranos was more accurate to mob reality than most TV or film.

To watch the series finale, we all flew to the Hard Rock Casino in Hollywood, Florida. Ten thousand people showed up to greet us on the red carpet. A few minutes after this shot was taken, we went into a small room to watch the finale—and for the first time, we all saw the now-infamous cut to black. (Courtesy of Steve Schirripa)

To watch the series finale, we all flew to the Hard Rock Casino in Hollywood, Florida. Ten thousand people showed up to greet us on the red carpet. A few minutes after this shot was taken, we went into a small room to watch the finale—and for the first time, we all saw the now-infamous cut to black. (Courtesy of Steve Schirripa)

______________________________________________________

From the book Woke Up This Morning: The Definitive Oral History of The Sopranos by Michael Imperioli and Steve Schirripa. Copyright © 2021 by Michael Imperioli and Steve Schirripa. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.