What Time Provides: Mining the Creative Unconscious For Inspiration

Victoria Redel on Taking Decades to Return To a Once-Abandoned Story

More than twenty years ago, I walked into Kremer Pigment, a small shop in lower Manhattan, and by the time I left, I had the idea for a novel—a story about pigment—and had signed up for a workshop in traditional paint-making recipes and techniques. For the next year, I read books on color and the global pigment trade, attended workshops, ground malachite and azurite, and macerated flowers. I lined the shelf above my writing desk with small jars of green, blue, rose pigment, eggshell white, and ink made from walnut and gall. I loved how things became other things—how a rock, an insect, dirt, eventually became the blue shadow, the red cape, the brown leaf on a canvas.

I filled notebooks with paint recipes and glazes. Read Vasari. Read Cennini’s, The Craftsman’s Handbook. I had my book title: The Dye Merchant’s Daughter, the protagonist a spunky girl who, by necessity, takes up her father’s trade. Soon there were sixty pages that I liked. A literary journal published the opening chapter. I was on my way.

It was as if for years I’d circled a field, looking for the gate in. And now, here was the gate, ajar, waiting for me to walk through.

But the way went nowhere. I wrote sentences. Wrote scenes. But it all felt labored. I kept working to invent heat rather than ever feeling that essential urgency of situation, character and story. I couldn’t even figure out what century I was in, and I pretended that didn’t matter. Just write and you’ll stumble into the mystery, I told myself. I contemplated structuring the book as a diptych. In the unnamed time and place, an orphaned girl searches for her lost father and by necessity steps into his trade. And in the 1980s, a downtown-NYC-all-the-rage feminist painter exploits her female studio assistants. The two parts didn’t cohere. I wrote and wrote until I finally gave up, scrapped the idea, and turned my attention to other fictions that pressed at my heart. I chalked up the paint novel to a failure. When I wrote a short story about an aged color field painter in Provincetown, who, having gone blind, hires young artists to read Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists, I thought, okay, at least all my reading wasn’t for naught.

But what does that even mean, for naught? As if what delights and obsesses us must have a purpose. Or that we can trace how what we read worms through the soil of our unconscious, aerating, seeding, and perhaps popping up in surprising new configurations. Could it be that scrapping a book is hardly ever that—scrapping—a word both dismissive and final. So much more generous to consider that what we need to write gets turned over in the quiet of the unconscious, living in the folds of the imagination while the initial spark deepens and prepares. It is hard to trust that the unconscious, over the years, does active work invisible to the writer. That if we attend to our craft with patience and commitment, we might be ready when the unconscious makes an offering. That we must learn to live with attentive receptivity. But all too often in the hurry to find the next story, novel, or poem, we ignore what time and patience provide.

Grace Paley once showed me a folder of story starts that, according to her, hit a wall and weren’t going anywhere. There were bits of stories, some just a couple paragraphs, others a few pages, some more than twenty years old. Every once in a while, reading through the folder, she saw a clear way forward on a story she’d thought was a dud.

In 2019, I went to Amsterdam hoping to finish a collection of poems. I wrote in the Rijksmuseum library. Working in one of the largest art libraries in the world, I felt the old tug for a novel about paint resurface. It wasn’t in the library, but in Russell Shorto’s book, Amsterdam, that I stumbled on Maria van Oosterwijck, a little remembered Dutch painter of the Golden Age. She intrigued me, but it was when I learned of Gerta Pieters Wyntges, her servant turned paint preparer and painter, that a buzzy urgency lacking years before was, unmistakably, present. Gerta, as a historical figure, is primarily known as an appendage to Maria’s career. But who was Gerta? I knew Gerta needed to be the novel’s lens. She would tell the story. It was as if for years I’d circled a field, looking for the gate in. And now, here was the gate, ajar, waiting for me to walk through.

Time and the connective work of the unconscious had slowly taken one idea and made essential leaps that I wasn’t ready or able to imagine twenty years earlier.

Each day, after leaving the library, I wandered the restored canal streets of Amsterdam, imagining Gerta in the 1600s as she maneuvered the busy, fetid thoroughfares. One afternoon, two sentences formed in my mind—I was shy of eight when I was put out to work. The family that took me in was in need of a boy, and so it was a boy I became. I knew these were the novel’s opening sentences. And with those sentences, glimpsed that Gerta was also Pieter, a transformational and fluid character. While she’d pulverize and grind rocks and turn one substance into another, she too would shift.

Her discovery, her self-creation, her passion, and emergence as an artist felt braided with what had originally fascinated me about paint-making. Transformation in all its transgressive aspect had been part of my original obsession with pigment, that step by strange step—adding, grinding, titrating, burning, sometimes burying for more than a year—something becomes another thing. But my initial obsession had lacked characters who might also enact their own shift. Now the lengthy process of preparing ink or turning lapis into blue paint was bound to Gerta’s complex and riddled devotion and love of Maria, and eventually to the shaping of herself as an artist.

Because Maria and Gerta/Pieter were primarily still-life flower painters, I dove into research on flower morphology and botanical art and found another wonderfully mysterious connection. The tulip, the rose, and the lily are bisexual or perfect flowers containing both male and female reproductive parts. “In each of us two powers preside, one male, one female,” wrote Virginia Woolf. Just as Gerta/Pieter seemed inextricably linked to the preparation of colors, her queerness and gender switching felt oddly akin to the flowers she learned to paint. In I Am You, where gender has been chosen for Gerta—brought into a family as a boy then revealed to be a girl for Maria’s need—it is Gerta/Pieter who finally elects to live both male and female according to her own desires.

One thing over time becomes something else. Hadn’t that also happened to me as a writer? Time and the connective work of the unconscious had slowly taken one idea and made essential leaps that I wasn’t ready or able to imagine twenty years earlier. The mind, it turned out, was no different than Paley’s folder filled with stories that hit a wall. How often had I felt the nub of something but had felt unable to tease it into a whole story or poem? How often in my impatience and frustration had I not trusted that if I waited with open attention, I’d find a way in or find, with surprise, the old concerns emerge in what I’d believed was wholly other work. Could it be that nothing is wasted? Or that tossed off, scrapped, relegated to the dung heap of failed work, the unconscious keeps turning and turning the deep images and obsessions.

I’m grateful that the girl I’d imagined twenty years ago resisted being conjured into being, though I love that, without any intention on my part, Gerta bears traces of her spunky nature. Mostly, I’m grateful for my insistent and unruly unconsciousness and the grace of time.

__________________________________

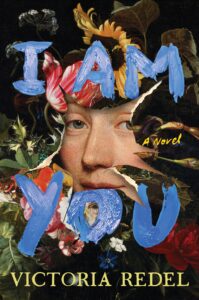

I Am You by Victoria Redel is available from SJP Lit/Zando.

Victoria Redel

Victoria Redel has written four books of poetry and six books of fiction. Her short stories, poetry, and essays have appeared in Granta, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and BOMB, and she’s received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Fine Arts Work Center. Victoria is a professor at Sarah Lawrence College and splits her time between New York City and Utah.