What the Picture Knows: Books That Seamlessly Blend Text and Image

Caleb Klaces on the Often-Overlooked Role of Photography in Works of Fiction

According to linguist David Crystal, once a person has learned to read, it is almost impossible to process the graphic marks that make up a letter as anything but a letter. At some point, we stop looking and start reading. If a fiction writer uses photographs, they ask a reader both to read and to look. It’s messy—like eating while driving. Photographs also complicate the suspension of disbelief. If a photograph evidences something that really happened, what is it doing in a story of imaginary events? These complexities might explain why photographs in fiction are often passed over in awkward silence.

John Berger makes an argument that it’s the difference between text and image that makes the combination fruitful. In an introduction to I Could Read the Sky, writer Timothy O’Grady and photographer Steve Pyke’s 1997 novel about twentieth-century Irish emigration, Berger describes how “they work together, the written lines and the pictures, and they never say the same thing. They don’t know the same things, and this is the secret of living together.”

What follows is a brief, partial tour through some visual touchstones from the last century of fiction—thinking, in particular, about what the picture “knows” that the words do not.

*

The Quincunx

WG Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (1998) narrates a solitary walk around the sand dunes, power stations, and empty hotels of Suffolk. Some photographs appear to be taken by the author. The boxy Rover parked outside Lowestoft station is particularly evocative for a British child of the eighties and nineties. To the same reader, other images feel more improbable: the view from inside a miniature model of the Temple of Jerusalem; the Dowager Empress with her senior eunuch Li Lien-ying; a Chinese quail, captured at ground-level, “in a state of dementia.” There is the strange feeling that the fiction itself has somehow generated the images.

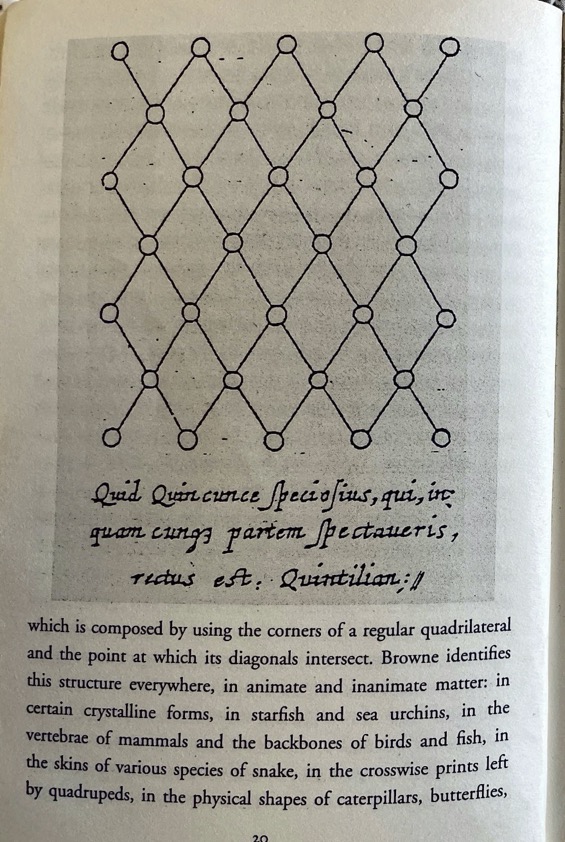

Early on, we see the “quincunx,” a lattice structure that the seventeenth-century author and natural philosopher Thomas Browne glimpsed “in the physical shapes of caterpillars, butterflies, silkworms […] the pyramids of Egypt and the mausoleum of Augustus.” It becomes clear, eventually, that this is a visual key to the quincunx structure of the book itself. Sebald encourages a state of reading where epiphany and paranoia are twinned. Suddenly, every image speaks to all the others: a wood scattered with dead bodies, fishermen shin-deep in a glut of herring, the author in front of a Lebanese cedar, accompanying a discussion of Dutch Elm Disease.

Eyes

Sebald’s Austerlitz opens with eyes in the darkness. In the Antwerp Nocturama, the eyes of the nocturnal creatures remind the narrator of the “inquiring gaze found in certain painters and philosophers who seek to penetrate the darkness which surrounds us purely by means of looking and thinking.” Here they are, in rectangular strips: the eyes of jerboa, owl, Jan Peter Tripp, Ludwig Wittgenstein. The narrator’s faith in this flimsy visual evidence is childlike. At the same time, it is shocking, even as an adult, when a book opens its eyes and looks back.

There is the strange feeling that the fiction itself has somehow generated the images.

In Amy Sackville’s Painter to the King (2018), the King of Spain complains to Diego Velazquez, “I’m so tired of seeing myself in your mirrors.” The novel is told from the point-of-view of the court painter. The sly, bespectacled eyes of one of his subjects, Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas, look out from an early page—it’s intimidating. The feeling of being watched lingers. For Diego, a misplaced stroke could be costly.

Empty City Streets

It was through Sebald that I discovered the Vertigo blog, run by Terry Pitts, which opened my eyes to the breadth of “photo-embedded literature.” Vertigo is a brilliant combination of data—Vertigo Terry always reports on the number of images in a book, and where he thinks they have come from—and honest accounts of what it is actually like to read often difficult books.

I learned that the first mass-produced volume to be photographically illustrated was a “tour of art, architecture, and nature” published in 1844 by William Henry Fox Talbot. The Pencil of Nature included photographs of Paris boulevards. They were empty. That is because pedestrians and carriages did not remain in front of the lens long enough to be captured by Talbot’s early photographic process, the “Talbotype.”

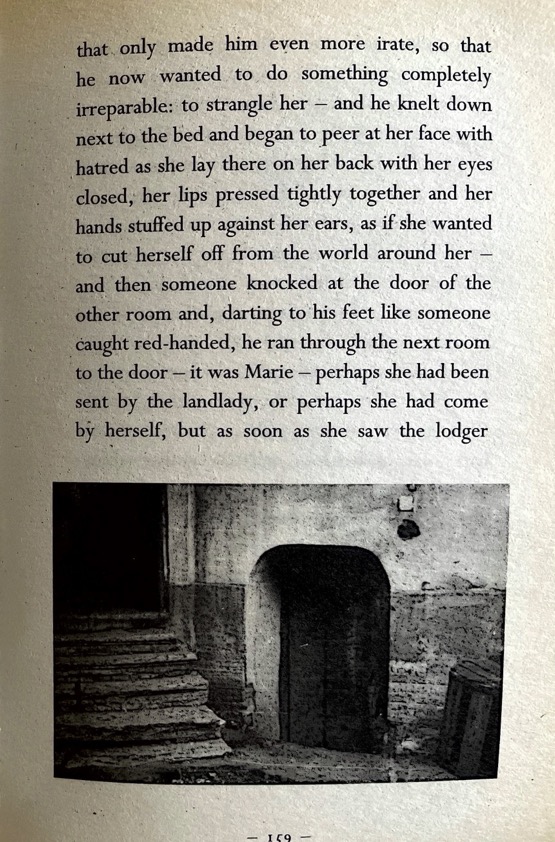

Photographs can act like an empty stage set for the action of the words. Andre Breton’s Nadja (1928) is a novel about the surrealist narrator’s dubious infatuation with Nadja, a woman he meets by chance one day. The text is excitable and wayward, while many of the photographs are dramatically dull. Here are some empty brasserie tables. Here is a park fountain. This “voluntary banality,” as Michel Beaujour has called it, also runs through Leonyd Tsypkin’s Summer in Baden-Baden (1981), about Anna and Fyodor Dostovesky’s honeymoon. Tsypkin’s account of dramatic summer of gambling and deathbed prayers is accompanied by his own melancholic photographs of nondescript walls and windows, taken on a research trip to Leningrad. Caleb Femi’s Poor (2020) sets up a visual contrast between exterior shots of the cold geometric grid of the North Peckham Estate, and close-up interiors with dancing. The poem “Concrete (III)” begins: “concrete is the lining of the womb / that holds boys with their mothers.”

Portraits

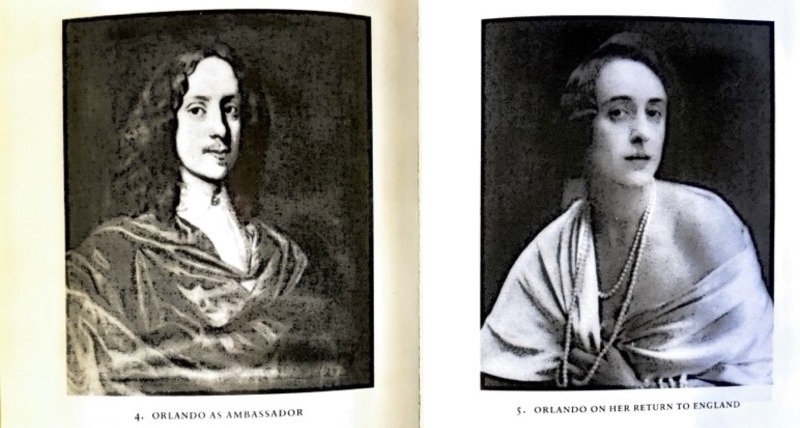

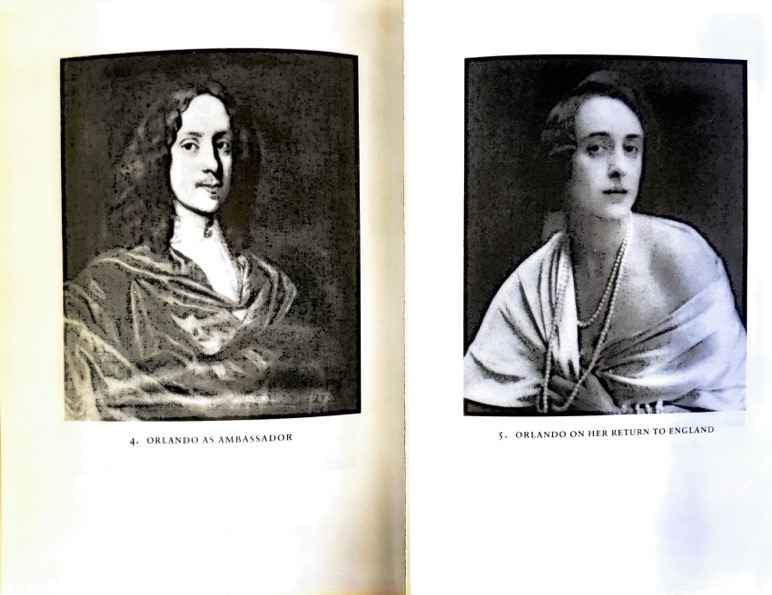

When I first read Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928), I couldn’t get a handle on its tone: omniscient, flippant, infatuated. It was only when I came to the photographs—printed on central plates—that I understood its parody of biography. The photographs joyfully corroborate the text’s account of a life that cannot be the case. The first image, “ORLANDO AS A BOY,” shows an Elizabethan child. The boy eventually grows up to be the woman captured, roughly 350 years later, in the final photograph, “ORLANDO AT THE PRESENT TIME.” The images seem to mock the idea that it’s possible to access the past—and the arbitrary conventions of inheritance. Some of them were staged by Woolf. The rest she found in the collection of Knole House, the country estate where Vita Sackville-West grew up, but could not inherit because she was a woman.

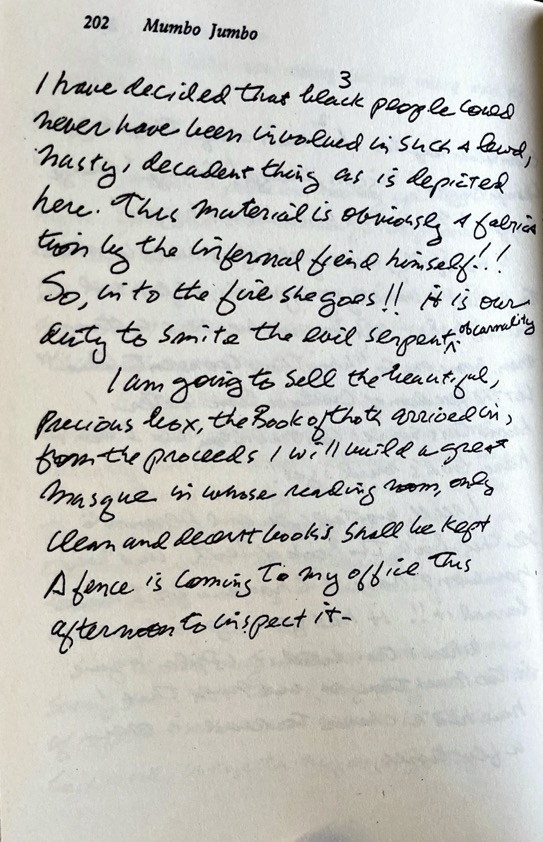

Handwriting

Here are just some of the “photo-embedded” books that contain images of handwriting: Nadja, The Rings of Saturn, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (1982), Javier Marias’s Dark Back of Time (2001), Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed (1972). All of these writers want to show us that someone, at some point, really used a pen. Perhaps the use of photographs induces a nostalgia for an imagined time before photography existed? Perhaps it makes writers anxious that writing itself, as a physical activity, will be replaced? Perhaps writers should get out more often?

What Cannot Be Seen

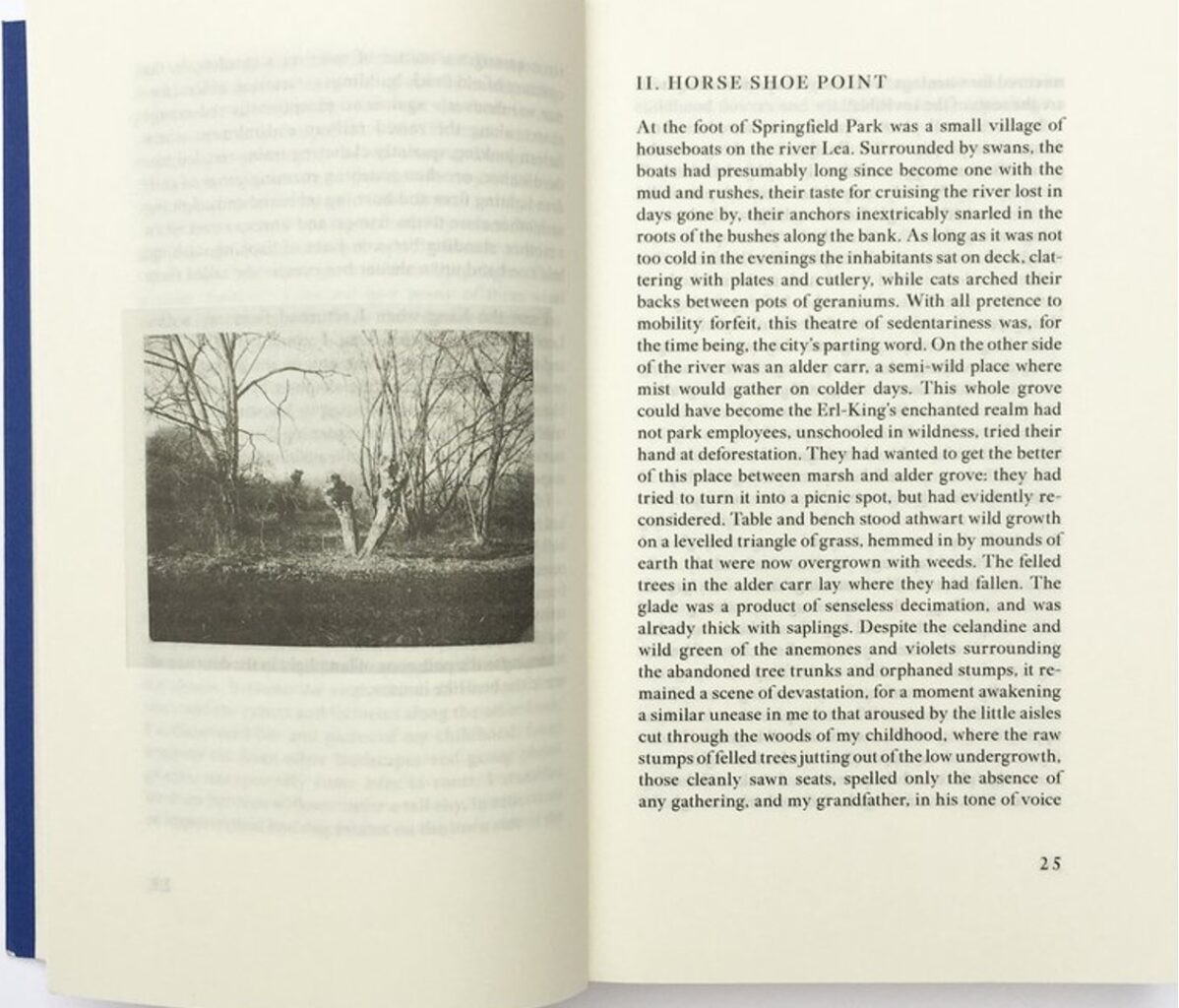

In Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive (2019), two adults and two children go on a road trip through the American South. The sun-bleached polaroids taken by the narrator’s son are part of the novel’s exploration of “documentation.” For unaccompanied migrant children passing through the same landscape, lack of appropriate evidence might be a matter of life and death. In Esther Kinsky’s River (2018), the narrator—whose father was an amateur photographer—picks up an old polaroid camera and takes it with her on her walks along the river Lea in East London. The images seem to capture something more than the light reflecting off the surface in front of the lens: “The images belonged to a past I could not even be sure was my own, touching on something whose name I must have forgotten, or possible never knew.”

__________________________________

Mr. Outside by Caleb Klaces is available from Prototype Publishing.

Caleb Klaces

Caleb Klaces is the author of the novel Fatherhood, which won a Northern Writers Award and was longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize, and the poetry collections Away From Me and Bottled Air, which won an Eric Gregory Award and the Melita Hume Prize. He grew up in Birmingham.