What the Obamas' Portraits Reveal About the Changing American Art Canon

On Kehinde Wiley and the Artistic Vision of the Obama White House

On February 12th, 2018, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery unveiled the portraits of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama. The White House and the museum had worked together to commission the paintings, and, in many ways, the lead-up to the ceremony had followed tradition. But this time something was different.

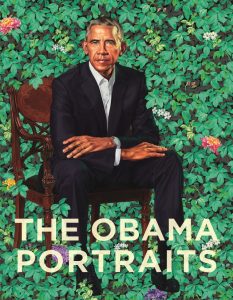

The atmosphere was infused with the coolness of the there-present Obamas, and the event, which was made memorable with speeches from the sitters, the artists, and Smithsonian officials, erupted with applause at the first glimpse of these two highly unconventional portraits. Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of the president portrays a man of extraordinary presence, sitting on an ornate chair in the midst of a lush botanical setting. Amy Sherald’s portrait presents a statuesque and contemplative first lady, posed in front of a sky-blue background.

As a true marker of our era of connectedness, those watching the unveiling were invited to post their impressions on social media. While some criticized the paintings as being too distant from traditional presidential portraiture and debated the likeness of Sherald’s depiction, the critical and public responses were overwhelmingly positive. During the first two weeks that the portraits were on view, over 4,100 press articles covering the unveiling reached an estimated 1.25 billion people worldwide.

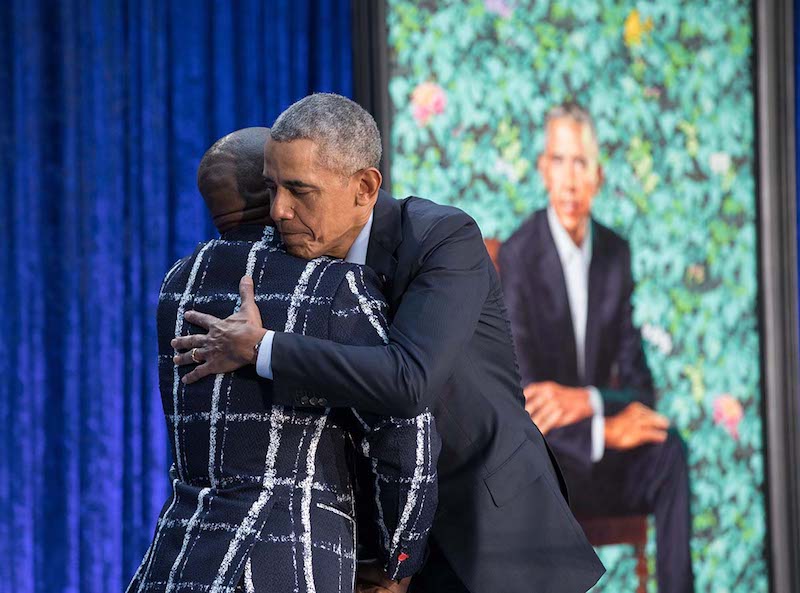

President Barack Obama examines his portrait during the unveiling ceremony on February 12, 2018. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Photo © Foto Briceno

President Barack Obama examines his portrait during the unveiling ceremony on February 12, 2018. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Photo © Foto Briceno

Meanwhile, visitors waited in line for up to 90 minutes to see the portraits. In October 2018, the museum’s calculations confirmed that the Obama portraits had produced a blockbuster, increasing annual attendance from 1.1 to 2.1 million. The impact that these paintings have had on art, on the National Portrait Gallery, and on American society is unprecedented, particularly when thinking about them as a pair.

The day after the unveiling, President Obama’s portrait was installed in the museum’s hallmark exhibition America’s Presidents, bookending the chronological display that opens with Gilbert Stuart’s “Lansdowne” portrait of George Washington. With the exception of a handful of paintings—including the dramatic full-body portrait of Abraham Lincoln by George Peter Alexander Healy; the portrait of Grover Cleveland by Swedish artist Anders Zorn, with its painterly brushstrokes and sumptuous reds; and the Abstract Expressionist portrait of John F. Kennedy by Elaine de Kooning, with its fast, vivid green brushwork—presidential portraiture is a genre characterized by an elegant modesty that facilitates a sense of shared identity and image.

Portrait unveiling of former President Barack Obama and former First Lady Michelle Obama at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., Feb. 12, 2018.

Portrait unveiling of former President Barack Obama and former First Lady Michelle Obama at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., Feb. 12, 2018.Photo by Pete Souza

Most often these portraits are realistic representations that contain a reference to the office by way of interior setting and an air of reasonable authority. It should be noted that while walking through the exhibition and passing one presidential countenance after another, it is impossible to ignore that viewers are in the exclusive company of older white men. Both Wiley’s and Sherald’s re-envisioning of State portraiture to represent the first African American president and first lady has captured the public imagination in a way that would not have been possible had the artists followed a more academic template.

In order to fully grasp the impact of these paintings, it is necessary to familiarize oneself with the symbolic place they inhabit. Although the National Portrait Gallery’s large collection comprises portraits of Americans who have contributed to history in myriad ways, the museum is best known for its complete collection of presidential portraits—the only one of its kind outside the White House.

The permanent exhibition America’s Presidents presents oil-on-canvas portraits of each former chief executive. The medium “oil on canvas” is highly significant because it carries a sense of tradition, formality, elegance, and permanence. Nevertheless, the museum also displays drawings, prints, photographs, and sculptures in its hall of presidents to offer further insight into each leader’s historical context and public image.

Michelle Obama and Amy Sherald stand alongside the newly unveiled portrait of the former first lady at the ceremony on February 12, 2018. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Photo © Pete Souza

Michelle Obama and Amy Sherald stand alongside the newly unveiled portrait of the former first lady at the ceremony on February 12, 2018. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Photo © Pete Souza

Millions of Americans travel to Washington, DC, each year, often as part of a patriotic journey, and many of those who visit the National Portrait Gallery have told us, through comment cards, that they see America’s Presidents as symbolic of this country’s democracy. One can, after all, rely on this singular collection of paintings to frame a larger story of the United States.

With the addition of each new portrait, the exhibition keeps time—not only in terms of the office but also in terms of American history. And once each presidential portrait is completed, it joins the others to set the tone and expectations for those to come in the future.

The Obama portraits came slowly into existence, in accordance with the National Portrait Gallery’s tradition of commissioning portraits of the departing president and first lady. The process took over two years from the initial conversations to the final unveiling. First, the museum’s curators submitted approximately 15 portfolios of possible artists to the White House. After months of deliberation with advisors, including the official Curator of the White House, William “Bill” G. Allman, and other fine art consultants, the Obamas created a shortlist of artists whom they interviewed in the Oval Office.

They reached a decision by January 2017, and for the next 10 months, their selection of Wiley and Sherald was kept secret, as it had been for past presidents. But the news leaked that October, and the Wall Street Journal issued a story entitled “Obamas Choose Rising Stars to Paint Their Official Portraits,” instantly provoking excitement and triggering speculation as to what the portraits would look like.

The museum’s prior presidential portrait commissions had never been so highly anticipated, and none had been widely publicized before their unveiling. The tradition was viewed as a national ritual, one characterized by its detachment from the contemporary art world. President Obama’s decision to grant Kehinde Wiley the opportunity to paint his portrait sent a powerful message and recast this dynamic.

The National Portrait Gallery welcomed more than two million visitors in FY2018, nearly doubling its annual attendance records. Most individuals who came to see the portraits in person used their phones to document their personal encounters. Photo(s) by Paul Morigi

The National Portrait Gallery welcomed more than two million visitors in FY2018, nearly doubling its annual attendance records. Most individuals who came to see the portraits in person used their phones to document their personal encounters. Photo(s) by Paul Morigi

The Obamas’ choices were bold yet not altogether unexpected. As one of the youngest couples to inhabit the White House, they consistently projected themselves as current and trendsetting. And in a strong effort to “personalize their home,” they borrowed art from museums and acquired works for the White House collection that aligned with their personal tastes.

Their level of interest in American art, particularly contemporary art, was unprecedented for a presidential family, and the artworks they displayed over the course of President Obama’s two terms in office ranged from George Catlin’s 19th-century scenes of Native American life to a contemporary painting by Ed Ruscha entitled I Think I’ll . . . , which can be read as a deadpan comment on the constant decision-making process involved in the presidency.

Another work the Obamas displayed in the White House was Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (Black Like Me #2) (1992), the title of which is taken from the 1959 nonfiction book by John Howard Griffin, in which Griffin, a white journalist, darkens his skin in order to report on racism and injustice in the Jim Crow South. To make the painting, Ligon used a black paint stick to repeatedly stencil “All traces of the Griffin I had been were wiped from existence” on a white canvas until the words became illegible.

Together, these artworks by Catlin, Ruscha, and Ligon represent the range of the Obamas’ artistic sensibilities as well as their understanding of the power of art to transmit a multitude of messages. Their choices reflect a reverence for history and the nation’s cultural foundations; a non-nostalgic vision of the past; witty, self-reflexive humor; and a celebration of free and creative thinking.

The Obamas are mindful of how inclusion within the canon can secure a place in history for artists, so in 2015, they brought work by Alma Thomas into the White House Collection. One of the most distinguished members of the Washington Color School, Thomas became the first African American woman to enter into the prestigious collection.

President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, and their daughter Malia look at Alexander Gardner’s 1865 photograph of Abraham Lincoln during a visit to the National Portrait Gallery in 2014. White House Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, and their daughter Malia look at Alexander Gardner’s 1865 photograph of Abraham Lincoln during a visit to the National Portrait Gallery in 2014. White House Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Thomas’s painting Resurrection was installed in the White House Family Dining Room, in dialogue with works by other masters of 20th-century abstraction, including Josef and Anni Albers and Robert Rauschenberg. The painting was made with rhythmically applied dabs of paint shaped into concentric circles, which radiated with brilliance at the head of the dining table.

President Obama’s choice of Kehinde Wiley (b. 1977) and Michelle Obama’s choice of Amy Sherald (b. 1973) align with the first couple’s artistic vision. The two African American artists were at very different stages in their careers when they were selected to paint the portraits of the Obamas, but both were already firmly rooted in the genre of portraiture, albeit with a contemporary outlook.

In distinct ways, Wiley and Sherald are committed to making black people present in painting: in portraiture, in museums, and by extension, in the American cultural imagination. Through experimentation and by plainly subverting the genre’s conventions, both artists take on this task deliberately in order to bestow dignity and humanity on those who have for centuries been marginal or invisible in the Western canon.

As documents of both the Obamas’ White House tenure and contemporary artworks that challenge tradition, these portraits cement the Obamas’ reputation as powerful shapers of history who are also modern, innovative taste-makers with a brand of their own. At the same time, the entry of these portraits into the museum’s collection represents a significant moment in the institution’s recent sustained effort to evolve longstanding ideas about the nature of American portraiture and its power through time to determine who is inscribed in this nation’s history and who is erased.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Obama Portraits by Taína Caragol, Dorothy Moss, Richard J. Powell, and Kim Sajet. Copyright © 2020 by Smithsonian Institution. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Taína Caragol

Taína Caragol is curator of painting and sculpture and Latino art and history at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC.