What the Great Russian Writers Didn't Get About the Criminal Mind

Varlam Shamalov Served 15 Years in a Soviet Labor Camp

Fiction has always represented the criminal world sympathetically, sometimes sycophantically. Deceived by cheap and tawdry ideas, it has given the world of thieves a romantic aura. Fiction writers have been unable to see through the aura to the actual revolting reality of that world. This deception is a pedagogical sin, a mistake for which our young people are paying a high price. You can forgive a boy of 14 or 15 for being thrilled by the “heroic” figures of the criminal world, but you can’t forgive a writer.

Yet even among great writers we cannot find any who are able to discern the thief’s true character and to reject or condemn him, as all great artists should condemn that which is morally bad. Moreover, historically the most enthusiastic preachers of conscience and honor, for example, Victor Hugo, have often used their gifts to praise the criminal world. Hugo was under the illusion that this world was a part of society engaged in a strong, decisive, and public protest against the false world of power.

But Hugo didn’t bother to examine what the position that this community of thieves adopted to struggle against the state authority entailed. Quite a few young boys have tried to befriend real misérables after reading Hugo’s novels. Even today Jean Valjean is a popular nickname among gangsters.

In his Notes from the House of the Dead, Dostoyevsky avoids giving a direct, categorical answer to the question of real criminality. All his Petrovs, Luchkas, Sushilovs, and Gazins were, as far as the criminal world of real gangsters was concerned, just “suckers,” freiers, “pushovers,” “oafs”—in other words, the sort of people the gangsters despised, robbed, and trampled on. Gangsters saw murderers and thieves like Petrov and Sushilov as resembling the author of Notes from the House of the Dead more than they resembled themselves.

Dostoyevsky’s thieves were as likely to be attacked or robbed as the hero Aleksandr Gorianchikov and his equals, however wide the chasm that separated this criminal gentry from the ordinary people. After all, a thief is not just someone who has stolen something. You don’t have to be a gangster to belong to that foul underground order, to steal something or even to thieve systematically. Apparently, when Dostoyevsky was doing hard labor, this category of the gangster didn’t exist. Gangsters are not usually punished with very long terms of imprisonment, for most of them are not murderers. Or rather, in Dostoyevsky’s time they weren’t.

There weren’t too many people in the criminal world who were prepared to “whack” anyone, whose hands were “brazen.” The basic categories of crooks or cons, as the criminals called themselves, were “cracksmen,” “filchers,” fences, pickpockets. The phrase “criminal world” is an expression that has a specific meaning. Crook, con, cove, gangster are all synonyms. Doing hard labor, Dostoyevsky did not encounter any of them, and if he had, we might very well have been deprived of the best pages in his book, pages where he affirms his faith in human nature.

None of Dostoyevsky’s novels contains a single gangster. Dostoyevsky never knew them.

But Dostoyevsky did not encounter gangsters. The convict heroes of Notes from the House of the Dead are just as peripheral to real criminality as the main hero Gorianchikov. For instance, was stealing from one another, something that Dostoyevsky dwells on several times and emphasizes in particular, really possible in the gangsters’ world? They went in for robbing freiers, sharing the loot, playing cards, and then finally losing possessions to various master criminals, depending on the outcome of their games of poker or pontoon. In Notes from the House of the Dead, Gazin sells alcohol, as do other “barmen.” But gangsters would have instantly taken Gazin’s alcohol, and his career would have been nipped in the bud.

Traditional “law” dictated that no gangster ever worked when in prison: the freiers had to do his work. Dostoyevsky’s Miasnikovs and Varlamovs would have been called by the contemptuous criminal name “Volga dockers.” None of those sneaks, louts, and pilferers have anything to do with the gangster world, the world of recidivist convicts. They’re just people caught up in the negative side of the law, entangled by chance, or overstepping some limit in the dark, like Akim Akimovich, a typical “freier fool.”

The gangster world is a world with its own laws; it is eternally at war with the world represented by Akim Akimovich or Petrov, as well as the eight-eyed deputy commandant. In fact, the deputy commandant is closer to the professional criminals. He’s their God-given boss, so that their relationship with him is as simple as with any representative of authority: anyone like him will hear a lot of talk from a gangster about fairness, honor, and other lofty subjects. And it has been going on for centuries. The pimply, naïve deputy commandant is the gangsters’ declared enemy, but the Akim Akimoviches and the Petrovs are their victims.

None of Dostoyevsky’s novels contains a single gangster. Dostoyevsky never knew them, and if he did see and know them, then, as an artist, he turned his back on them.

Tolstoy doesn’t have any memorable portraits of this sort of person either, even in Resurrection where the external and illustrative descriptive brushwork is done in such a way that the artist cannot be held responsible for his criminal characters.

Chekhov did come across this world. Something in his journey to Sakhalin changed the way he wrote. In a few of his letters after Sakhalin, Chekhov clearly indicates that everything he’d written before the journey seemed to him to be trivia unworthy of a Russian writer. Just as in Notes from the House of the Dead, the stupefying and debauching foulness of the prisons on the island of Sakhalin inevitably destroys anything pure, good, or human.

The criminal world horrifies the writer. Chekhov senses that this world is the chief battery of the foulness, a sort of atomic reactor that creates its own fuel. But all Chekhov could do was wring his hands, smile sadly, and point out this world with a mild, albeit insistent, gesture. He, too, knew it from reading Hugo. Chekhov was in Sakhalin for too short a time, and until the day he died he lacked the boldness to use this material for his fiction.

The gangster world is a closed, if not particularly secretive order, and outsiders who want to study and observe it are not allowed in.

One might think that the biographical side of Gorky’s work would give him a reason to show the gangster world truthfully and critically. His Chelkash is undoubtedly a gangster. But this recidivist thief is portrayed in Gorky’s story with the same forced pretense at fidelity as the hero of Les Misérables. Gavrila, of course, can be interpreted as something more than just a symbol of the peasant soul. He is the pupil of the old crook Chelkash, perhaps by chance, but nevertheless inevitably: a pupil who might the next day have become a “gutless wannabe” rises one rung higher on the ladder leading to the criminal world.

For as one philosopher, who also happened to be a criminal, said, “Nobody’s born a criminal; they become one.” In “Chelkash,” Gorky, who came across the criminal world in his youth, was just paying his dues to that ill-informed delight at what appears to be that social group’s freethinking and bold behavior.

Vaska Pepel (in The Lower Depths) is a very unlikely criminal. Just like Chelkash, he is romanticized and exalted, instead of being exposed for what he is. A few superficial, well-rendered features of this figure, and the author’s obvious sympathy, mean that Pepel, too, serves an evil cause.

Such are Gorky’s attempts to portray the criminal world. He too was ignorant of this world and had apparently never really encountered gangsters, for such encounters are generally difficult for a writer. The gangster world is a closed, if not particularly secretive order, and outsiders who want to study and observe it are not allowed in. No gangster would open up to Gorky the tramp, or to Gorky the writer, for Gorky is just another freier in the gangster’s eyes.

In the 1920s our literature was swept by a fashion for portraying robbers: Babel’s “Benya Krik,” Leonov’s The Thief, Selvinsky’s “Motke Malkhamoves,” Vera Inber’s poem “Vaska Svist Behind Bars,” Kaverin’s “The End of the Hide-out,” and, finally, Ilf and Petrov’s Ostap Bender. Every writer appears to have frivolously paid tribute to a sudden demand for romantic criminality.

This unbridled poetization of criminality was greeted as a fresh new current in literature, and it led many experienced literary writers astray. Although all the authors I have mentioned, as well as others not mentioned, show an extremely weak understanding of the essence of what they were dealing with in their works on this theme, they had great success with readers and consequently did a significant amount of harm.

Things got even worse. There was a prolonged period when people were carried away by the notorious fashion for “reforging,” the reforging that gangsters laughed at and are still laughing at just as loudly today. The Bolshevik and Liuberets communes were opened, 120 writers contributed to a “collective” book about the White Sea–Baltic Canal, and the book was published in a design that made it look like the New Testament.

The literary crown of this period was the play by Pogodin The Aristocrats, where the playwright repeated the old mistake for the thousandth time, not bothering to give any serious thought to the living people who gave a very elementary live performance for the benefit of a naïve writer. Many books, films, and plays about reeducating members of the criminal world have been published and staged. Alas!

Ever since Gutenberg began printing, the criminal world has been a sealed book for writers and readers. Writers who have tried to tackle this theme have dealt with it frivolously; they have let themselves be carried away and deceived by the phosphoric glare of criminality, they have disguised it with a romantic mask and thus reinforced their readers’ utterly false idea of what is in fact a treacherous, revolting, and inhuman world.

Fussing over various sorts of reforging has given many thousands of professional thieves a break and has been the salvation of gangsters. So what is the criminal world?

(1959)

__________________________________

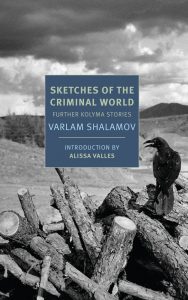

Sketches of the Criminal World was published in English by NYRB Classics. Translation copyright © 2020 by Donald Rayfield. All rights reserved.

Varlam Shalamov

After 15 years working in Russian labor camps for his counterrevolutionary activity, Varlam Shalamov wrote many volumes of poetry, including Ognivo (Flint, 1961) and Moskovskiye oblaka (Moscow Clouds, 1972). Severely weakened by his years in the camps, in 1979 Shalamov was committed to a decrepit nursing home north of Moscow. Following a heart attack in 1980, he dictated his final poems to the poet A. A. Morozov. In 1981, he was awarded the French PEN Club’s Liberty Prize; he died of pneumonia in 1982. Sketches of the Criminal World is available now from NYRB Classics.