What the Animal World Can Teach Us About Human Nature

A Conversation Between Carl Safina and Nick McDonell

I recently had the chance to talk with ecologist, professor, activist, and writer Carl Safina about his most recent book, Becoming Wild. It’s a precise and lyrical account of his investigations into three non-human cultures—sperm whale, scarlet macaw, and chimpanzee. In the company of some of the world’s foremost biologists, Safina sails and bushwhacks his way as close as one can get to these creatures, learning their traditions. Like ours, these pass generation to generation, cultural inheritances that shape lives as surely as genetics.

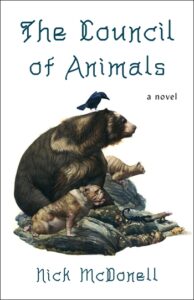

Our conversation about how that works touched on Darwin, metaphysics, hit Netflix series The Crown, the mysteries of humpback whale song, and much else. I was particularly glad to have it because of a novel I’ve written, called The Council of Animals, which is being published this summer. In it, seven animals gather to vote on the problem of humanity—which, even outside the covers of that book, seems sometimes to be getting out of hand (or paw or flipper, as the case may be). And in the tradition of great, humane naturalists, Safina’s scientific explorations ask how we, and all the other animals, can live together more easily.

A portion of our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity, is below.

*

Nick McDonell: In Becoming Wild, you reference Shakespeare, Melville, Emerson. There’s a lot of wonderful literary allusion in the book. I’m curious if there are particular books about animals that have stayed with you?

Carl Safina: Oh, geez. I know that there are going to be some important ones that that simply will not occur to me . . . But let’s start a little bit off, or beside, the track. I should preface by saying that I came to animals very organically, through animals themselves. I didn’t get taught something that I’ve then, like, field tested. It was my contact with animals that got me interested and made me want to delve, but that said: I remember when I was a very small child, I think before I could read, there was a book called The Camel Who Took A Walk, that, when I could finally sign my name, I checked out of the library numerous times. My father read it to me numerous times, I just thought it was really delightful. It’s a totally anthropomorphic story about how a whole bunch of animals conspire to thwart a Tiger’s impending attack on a camel that is taking a walk.

NM: Sounds great.

CS: Then there was a book that I read when I was in fifth or sixth grade, called The Incredible Journey, about, I think, two dogs and a cat that somehow got separated by about hundred miles from their owner and had to find their way home.

NM: I think there was a movie made of that one.

CS: And after that my mind goes just to nonfiction, my science education, I read Conrad Lorenz, those books made an impression on me. Donald Griffin, who I read in college. EO Wilson didn’t really write about animals, but his book Sociobiology—it was very affirming to read seven hundred pages by this great scientist, which said that mental abilities are evolved abilities.

In a conversation I was having with a physician that I was teaching with, he very matter of factly said: “Well, you know, birds appear when people die.”

NM: Speaking of evolution—you quote a really wonderful line from Darwin in the book: “he who understands a baboon would do more towards metaphysics than Locke.” Which got me thinking about the relationship between your study of nature and your own metaphysical beliefs. How has the changed over time?

CS: So this is interesting, and it factors into the book that I’m working on right now. Because in a sense, a lot of that book is intended to be—if I can pull it off—about people’s metaphysical views.

Views of nature and the cosmos tend to go immediately to religion and the spirit world. I was raised Catholic and became pretty un-Catholic by about the time I was twelve, but I always had the feeling: “I think there’s something else out there”—until about the time I graduated from college, when I just decided, “I really don’t think there are any spirits.” By which I mean: disembodied intelligences. And by intelligent, I mean consciously intelligent: they observe, they know, they think. I just don’t believe that any of those exist.

Large asterisk is that, maybe eight years ago or so, in a conversation I was having with a physician that I was teaching with, this physician very matter of factly said: “Well, you know, birds appear when people die.” And I thought, I actually don’t know that birds appear and when people die—but come to think of it, I remember this story about a friend of mine who had been a famous bird painter. On the day he died, this house wren came and was tapping and tapping on the window, like trying to get into the house, which is just . . . a weird thing. So I started to keep a file called “bird appearances upon death.” And after several years of keeping these anecdotes that I heard about—and a couple of things that happened to me that were like, whoa, that’s pretty weird—I realized that in many cultures birds are believed to appear upon death. We were even watching the series The Crown—you know what series I’m talking about?

NM: Yeah, I do.

CS: So we were watching The Crown. And there are two deaths in The Crown where immediately, like in the next jump cut, a bird, or a flock of birds, appears in a very weird way. So that’s in there. So my file on this has grown quite long. There are two entries with Peter Matthiessen. And it has moved me, after forty years, from being sure there is no disembodied experience, into: “I’m not so sure, exactly.” And also, at times of grief, the suspension of disbelief can be soothing. And I’m okay with that, from time to time. Not very conclusive. But I did feel very conclusive about it, before.

NM: Huh. There was this other passage in Becoming Wild, when you are out at sea with the sperm whales, that really struck me, along those lines: “For a little while, I am where I am best, among living manifestations of greater powers that long preceded me and may long outlast us all . . . For a short interval of time, they have tapped me awake and I feel at home in the world.” Can you tell me a little bit about that passage? What did you mean, “tapped you awake?”

CS: Well, I think that in most of our lives—our modern, industrial, working, going to the store, get the car fixed lives—we are mostly sleepwalking. We don’t pay attention to what’s right in front of our nose, and we feel these various pressures to get things done, stresses that are placed upon us. We live a hierarchical life where people tell us what to do, we have bosses, and it all revolves around our ability to have money or die. And all of those are things that did not exist for human beings during most of human history. And mostly, we don’t know where our water, or our food, or all the materials that are in our stuff—we don’t know where it came from, who made it ,or anything like that. We certainly don’t have a sense of continuity with the world or the deep past, or the fact that we’re just, you know, a tiny, tiny spark on a long, long continuum. That was the feeling I had, and that’s what that passage is about. We don’t often see ourselves enmeshed in a greater reality.

NM: On the topic of greater realities, or even mysteries—how about the humpback whale songs that remain so mysterious, that you mention in the book? It is fascinating to me that, for all the study of them, we still can’t figure out what that’s about. Could you talk a little bit about the mystery of humpback whale song?

CS: Really almost anything in the living world remains a mystery. You know, like, we don’t really know how chlorophyll works in a blade of grass, how it takes nonlife and eats sunlight and turns it into something alive. I mean, the mysteries are piled very, very, very deep.

But among them are some big fat ones like the humpback whales. Around 1970 we learned that they sing—after they’d been singing for many millions of years, and after people killed almost all of them. And we learned this extraordinary thing about how in any given ocean, the song changes simultaneously, among all the singers, every year. They sing one song one year, they change, and they sing differently the next year.

And yet, we don’t actually know why they sing. Because whales don’t really respond to each other in the way, for instance, birds do. Bird song, it’s pretty clear, is mostly territory, and saying “I’m here, I hold this place.” And that has to do with the functions of attracting potential mates, and keeping away potential rivals, and so on. But the whales don’t seem to act that way. We don’t really know what they’re saying, what they’re doing, why the song changes in this way.

And yet, it entangles our nervous system in a very interesting way—that people were so moved by hearing it that it tremendously accelerated the movement to save the remaining whales. To see them as beings, instead of just floating components of margarine and things like that. What moves them in this mysterious way that we don’t understand also moved us in an equally mysterious way that we don’t really understand. But we saw and felt a deep and great beauty and kinship. And we acted on that. And that’s very profound I think.

______________________________________

The Council of Animals by Nick McDonell is available now from Henry Holt.

Nick McDonell

Nick McDonell, born in 1984, is a writer of novels, journalism, and political theory. He studied literature at Harvard and international relations at St. Anthony’s College, Oxford. His fiction has been published in twenty-two languages and appeared on bestseller lists around the world. A film adaptation of his first novel, Twelve, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2010. His academic work on nomadism—The Civilization of Perpetual Movement—was published in 2016. As a reporter for the London Review of Books, Time, TheNewYorker.com, and Harper’s, Nick has embedded with the United States Army and Marines, the Afghan Special Forces, the African Union Mission to Darfur, and the Iraqi Special Forces. Nick’s last book, The Bodies in Person: An Account of Civilian Casualties in American Wars, was published in 2018. Nick is a cofounder of the Zomia Center for the Study of Non-State Spaces, which supports scholarly and humanitarian projects around the world.