What Makes Spiders So Terribly Scary to Human Beings?

Kate Summerscale on the Enduring Persistence of Arachnophobia

“Ladies seem to be particularly subject to arachnophobia,” observed the English parson and natural historian the Reverend John George Wood in 1863. If a spider scuttled across his drawing-room carpet, he said, the ladies of the household would “scream and jump upon chairs,” then “ring for the footman to crush the poor thing, and the housemaid to follow in his steps with dustpan and brush.”

Wood himself was delighted by arachnids (from the Greek arachnēs, or spider). He loved to see the spiders in his garden grow fat on the crane flies that he fed them at dusk. They would rush down from their webs, he said, to snatch the spindly insects from his fingers.

As many as 4 per cent of us are terrified by spiders—in most surveys, they come second only to snakes as objects of phobia. For the author Jenny Diski, autumn was an “annual festival of anxiety and horror,” because it was the season in which spiders came indoors to nest. On seeing a spider in the house, she would grab a blowtorch and, in a state of “desperate abandon,” blast flames at the creature. She knew that she risked starting a fire, she said, “but death was never a worse alternative to being in the same room as a spider. I suppose this sounds like a writer’s hyperbole, but I’m writing with all the accuracy I can muster.”

As many as 4 per cent of us are terrified by spiders—in most surveys, they come second only to snakes as objects of phobia.Many arachnophobes are sure that their aversion is instinctive. The writer and producer Charlie Brooker insists that his fear of these “mobile nightmare units” is a reflex, “a residual evolutionary trait that some people have and some don’t, just as some people can fold their tongues and others can’t.” If he sees a spider, he says, “I’m across the room before I know what’s happened, like an animal running from an explosion.”

Neurological research confirms that an arachnophobic reaction bypasses conscious thought: our primitive, emotional brain instantly processes the image of a spider—within milliseconds, the thalamus prompts the amygdala to release epinephrine, insulin and cortisol, increasing our pulse, blood pressure and rate of breathing in readiness for flight or a fight—while the prefrontal cortex more slowly assesses the risk and decides whether to cancel the amygdala’s preparations or to act upon them.

But a reflex can be learnt, and there is no obvious evolutionary reason for reacting to a spider in this way. Only about 0.1 per cent of the 50,000 or so spider species in the world are dangerous. There are far deadlier creatures that excite less horror. Spiders arguably even protect us by weaving webs that snare potential pests such as earwigs and flies. In an attempt to make evolutionary sense of arachnophobia, the biologist Tim Flannery speculated that there might have been a very dangerous spider in the part of Africa in which Homo sapiens first emerged as a species, and he looked for an arachnid that fitted the bill. He found one: the six-eyed sand spider (Sicarius hahnii) is a leathery, crablike creature that hides just beneath the surface of the southern African desert, ambushes its prey and has a venomous bite that can kill children. Our fear of spiders, says Flannery, might be a vestige of the moment in our evolution at which this creature posed a fatal threat.

There is a further oddity about our aversion to spiders. Scans of brain activity indicate that not only the amygdala is activated when an arachnophobe sees a spider, but also the insula, the part of the brain that generates the disgust response. Our facial reactions to seeing spiders bear this out: arachnophobes often tense and raise their upper lips in disgust, as well as raising their brows in fear. Researchers were initially surprised by such findings, since the disgust response is usually provoked by creatures and substances that might contaminate or infect us, and the spider does neither.

One explanation for this response—cultural as well as biological—is that we have adopted our medieval ancestors’ suspicion that spiders are carriers of disease. For hundreds of years, according to the psychologist Graham Davey, spiders were blamed for the plagues that afflicted Europe: it was not until the nineteenth century that rat-borne fleas were identified as the real agents of infection. Davey argued in a paper of 1994 that this myth of spiders as disease-carriers could explain the feelings of disgust that they provoke, since disgust responses are culturally conditioned as well as innate. Arachnophobia is common in countries populated by Europeans and their descendants, Davey notes, whereas in parts of Africa and the Caribbean spiders are not reviled as unclean but consumed as a delicacy.

When the Reverend Wood made his loving observations about the creatures in his garden in 1863, the image of the spider was undergoing a cultural transformation. In the eighteenth century, arachnids had been lauded for their industry, skill and creativity; their webs were hailed as wonders of the natural world. But in the Gothic fiction of the late nineteenth century, as Claire Charlotte McKechnie writes in the Journal of Victorian Culture, the spider became a sinister and sometimes racist trope: the hero of Bertram Mitford’s The Sign of the Spider (1896) fights a giant, carnivorous African spider that has “a head, as large as that of a man, black, hairy, bearing a strange resemblance to the most awful and cruel human face ever stamped with the devil’s image—whose dull, goggle eyes, fixed on the appalled ones of its discoverer, seemed to glow and burn with a truly diabolical glare.”

And in 1897 the naturalist Grant Allen made the wild claim that “for sheer ferocity and lust of blood, perhaps no creature on earth can equal that uncanny brute, the common garden spider. He is small, but he is savage.” McKechnie argues that spiders came to express “fears of invasion, concerns about the morality of colonialism, and suspicion about the alien other in the corners of empire.” Arachnophobia had become fused with xenophobia, and with anxiety about the repercussions of imperialism.

The spider’s symbolic meanings have continued to change. In 1922, Freud’s follower Karl Abraham proposed that the creature represented a voracious, ensnaring and castrating mother—”the penis embedded in the female genitals.” In 2012 the environmental philosopher Mick Smith argued that we fear spiders as emissaries from an anarchic natural world—insistent reminders of wilderness in a Western culture that has distinguished itself “precisely by its ability to separate itself from and culturally control nature.”

These silent creatures slip into our civilized domestic spaces on invisible threads, says Smith, finding the fissures in walls, adorning their sticky webs with insect corpses. He quotes Paul Shepard, an ecologist and philosopher who suggested that spiders had become “unconscious proxies for something else… as though they were invented to remind us of something we want to forget, but cannot remember either.” They disturb us because they are found in “the cracks that are the zones of separation, or under things, the surfaces between places.” They make us uncomfortable because they are creatures of the in-between.

In 2006 Jenny Diski tried to dispel her arachnophobia by enrolling on the Friendly Spider Programme at London Zoo. She and seventeen other arachnophobes discussed their feelings about spiders, listened to a talk on the subject, underwent a twenty-minute relaxation and hypnosis session (“Spiders are safe,” the hypnotist assured them) and then proceeded to the zoo’s Invertebrate House. To her astonishment, Diski was able to let one spider scamper across her palm, and to stroke the soft, hairy leg of another. She was cured. But “I have the strangest sense of loss,” she reflected. “A person who is not afraid of spiders is almost a definition of someone who is not me…Some way in which I knew myself has vanished.” If she rid herself of all her anxieties and nervous habits, she wondered if there would be anything of her left.

But a reflex can be learnt, and there is no obvious evolutionary reason for reacting to a spider in this way.A great many therapies have been developed for arachnophobia. In the same year that Diski was cured by a combination of hypnosis, education and real-life exposure, a forty-four-year-old British businessman was accidentally relieved of the phobia when he had an operation to remove his amygdala in a Brighton hospital. A week after the procedure, which was intended to stop his epileptic seizures, he noticed that he was no longer afraid of spiders. His level of fear was otherwise unaffected: he was as unfazed by snakes as he had been before the operation, he reported—and as anxious as ever about public speaking.

In the US in 2017, Paul Siegel and Joel Weinberger carried out a “very brief exposure” treatment for arachnophobia, whereby images of tarantulas were flashed up before phobic individuals (for .033 seconds) and followed at once with neutral, “masking” pictures of flowers. The experimental subjects were unaware of having seen spiders, and yet they afterwards reported less fear of the creatures and were able to get closer than before to a live tarantula in an aquarium. The effect held even after a year. The brain’s fear circuitry had been desensitized, even though the exposure was delivered unconsciously. When the same procedure was carried out with consciously registered spider images, the arachnophobes became distressed during the experiment, and showed no decrease in their spider-fear.

In 2015 two researchers at the University of Amsterdam tested another rapid cure for arachnophobia. Marieke Soeter and Merel Kindt exposed forty-five arachnophobes to a tarantula, for two minutes, and then gave half of the group a 40-milligram dose of propranolol, a beta-blocker that can be used to induce amnesia. They hoped that by activating and then erasing their subjects’ spider memories, they might also erase their fear of spiders. Their experiment drew on the neurologist Joseph LeDoux’s theory of memory reconsolidation, which proposed that memories retrieved via the amygdala are briefly malleable: a recollection could be altered or extinguished in the hours immediately after it is triggered.

The Dutch trial worked: the arachnophobes who had been given the amnesic drug were markedly less phobic than the control group, even a year later. A single, brief intervention, announced the researchers, had led to “a sudden, substantial and lasting loss of fear.” They described their revolutionary new treatment as “more like surgery than therapy.” They had not tempered arachnophobia, but excised it from the brain.

_____________________________________

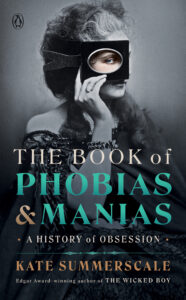

Excerpted from The Book of Phobias & Manias: A History of Obsession by Kate Summerscale. Copyright © 2022. Available from Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.