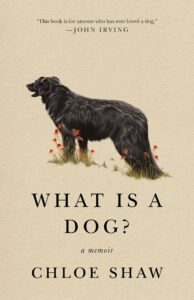

What Losing My Childhood Dog Taught Me About Grief and Companionship

Chloe Shaw Tries to Answer One Question: “What is a Dog?”

What is a dog? In the cosmic burnout of my bright, briny beginning, I didn’t yet know the answer to that question, same as I didn’t know the answer to: What is grief? What is a hummingbird? What is love? As I imagine it, eventually my mother or father must have pointed to our old Afghan hound, Easy, and said, “Dog.” Okay, I must have thought. I see the dog, but what is it? I see its eyes, its nose, its tail trailing hair like tentacles. But what is a tentacle? What is a dog?

My parents were newlyweds when they got her from a breeder, who, in addition to selling Egyptian puppies, was an organizer in the activist group Students for a Democratic Society in New Haven, Connecticut, where my parents lived while my dad attended architecture school. They’d been given a black cocker spaniel puppy named Clyde as a wedding gift, and they thought Clyde needed a friend—though eventually, Clyde would go to live in Texas with my dad’s aunt, who was lonely and grieving after her own dog had died. My mom had had Afghans on the brain ever since seeing them all over the Upper East Side when she was a student at Barnard.

Easy was officially named Ysé, a name my mom, the French major, found in French literature. That is where she also found the name Chloe, the Greek goddess of fertility, though I was nearly named Electra since my maiden name, Bland, seemed to beg for something a little electric. (I spent more than a few hours in my thirty-three years as Chloe Bland wondering who Electra Bland would have been—and from time to time I even tried to channel her, believing Electra capable of all the things Chloe wasn’t.)

Easy’s ancestral Egyptian name was Abaicor. But, in a rational nod toward our non-French, non-Egyptian heritage, she became good old American Easy. And good old American Easy followed my parents from New Haven, to Brooklyn, to Miami (where I was born), then back to Brooklyn for good.

Easy was my parents’ first baby—even in the way she first greeted me, their second baby, when they brought me home to Coconut Grove. My dad loves to describe how they presented her with this warm, swaddled-up, black-haired thing that was me. She took one sniff, lowered her head, and, like a demoted Disney dog, slinked back to her spot on the floor.

I wonder if she ever got over that feeling or if it just became part of her along with everything else to which wolves who’ve gone dog must adjust: stairs, crowded apartments, fire trucks. I was quite young and so don’t remember life with Easy particularly well, though somehow her sheer size suggests to me that I should.

I do, however, remember bits and pieces—her silky yellow hair, for one. I remember how she used to jump up on my babysitter, Birk, like a giant praying mantis wearing a blond wig. “Easy, Easy,” he loved to say. I remember our cat, Pearl—who’d quickly and understandably developed a distaste for me when I’d tried to get a doll dress over her head—sitting on the back of the gray couch, waiting to bat Easy’s tail whenever she walked by. I remember her shape, that sinewy silhouette, as it caught itself darkly before the sliding glass door to the green light of the garden at the back of our first Brooklyn apartment on Willow Street.

Like a proper sibling, I blamed her for things. When, at age four, I’d taken my unfulfilled desire for bangs into my own hands and hidden the chunk of hair I’d clipped from the not-so-center of my head under my bedroom chair, I declared the hair “Easy’s hair” after it was discovered by my mom while she was vacuuming. I declared this, of course, as she stared like a cat, unblinking, at the mini-Mohawk sticking up like a unicorn horn from my head.

*

I was four and a half when Easy suddenly collapsed in the kitchen. For years, I heard the sound of her nails trying to catch the floor—her last great act of life. My mother took her to the animal hospital in midtown Manhattan, and I never saw her again. Cancer is a word they used. But how can a word so invisibly wickedly fill a dog up?

Did Easy remember my mother’s miscarriage? I don’t. I don’t remember a lot of things that must remember me. My clenched, chubby baby fists and sopping, teething mouth inevitably filled with Easy’s hair. I don’t remember walks with her or touching her, hugging her, feeling her against me, the resident human baby. I don’t remember her smell. I don’t remember having a particular bond, more that we shared the same dashing parents and tidy, tasteful living room. This is pretty well illustrated in the numerous, now dilapidated, red photo albums still kept in my parents’ bookcase on the lowest shelf under all the architecture books. There are some photos of Easy and, once I came along, a million of me, but only a couple, I recall, of us together. Easy possessed the same enigmatic, well-groomed nature as my parents and left me in my clunky do-it-yourself-bang mess. I don’t remember her making me feel better about anything—or worse. She was an animal, and I remember her as such—snout, nails, hair. But what I remember best is what it felt like to be without her when she was gone.

A dog is nothing then. A dog is a dream I once had. A disappearance. A dog-shaped hole in an empty house.

*

On April 1, 1980, one week after Easy died, my family moved from our rental apartment on Willow Street around the corner to our purchased brownstone apartment on Pierrepont Street, where we lived in the top two floors. We shifted from life in the low, dark garden up into the big bright rectangle of sky. My parents bought the building with their friends the Vases: Meg, a concert pianist; George (who also played the piano), a Hungarian neurologist; and their musically gifted kids, Steven (cello) and Becky (piano), four and six years older than I was. It was unusual for the sound of their concert grand not to be skittering up through the floorboards, taking hold of teacups, ankle bones, and houseplants with the tiniest vibrations. Over the years, my parents and I developed the game of guessing which Vas was playing based on the music we heard. My mom always seemed to know best.

Easy was my parents’ first baby—even in the way she first greeted me, their second baby, when they brought me home to Coconut Grove.The building was sectioned into four separate units, one on each floor, so we essentially moved into a construction zone, living in the house while whole walls were struck down and before all the rooms as we’d know them were made. We walked on thick, dirty paper and greeted each other through plastic walls like Elliott’s family in E.T. We slept as a threesome all over the place, camping out wherever was cleanest and safest. My parents still talk about how awful that period was, living amid the mess, but, as the kid, I remember it as exciting, and probably only a quarter as long as it actually was. What I don’t remember is the sadness that they must have felt after losing Easy, their first baby, and the pregnancy, what would have been their third baby. Though maybe that all quietly fits under the “awful” umbrella of which my parents speak.

For reasons I believe were seeded long before they were born, the tendency in my family and my family’s families has been to swallow hard around hard things, to will big emotions back down. From my earliest memories, I gauged how good or bad things were by how quiet it got, how absent the bodies were around me, how fast they moved, as if motion could literally propel the bad stuff away. When things were good, bodies calmed so that I could see them. We could all go back to trying to look each other in the eyes.

Maybe it was easier that we’d moved so quickly away from that house where the dog-shaped hole still lay—the baby-shaped hole, too. Everyone got busy building a new home, a space that never knew the dog or the womb or the pain that losing both must have left. Our new life on Pierrepont Street moved forward as if there’d never been a dog or the hope for any other children but me. Easy never set foot in our Pierrepont Street home, and so there was nothing to divine from her absence there. No haunting traces. Only paint chips and sawdust to pick up. And what about their third? He or she, too, had scurried off with Easy now into the driving quiet. What didn’t I miss about the miscarriage I’d missed? Where in a body does grief you dare not speak of go? Was it grief that grew a mass on my cousin Morley’s spine, years after her sister Anne died sleepwalking out a fourth-story window? Was it grief that turned the ladybug on the dead body of a dear friend’s mother into her mother? Grief holds the body itself hostage sometimes. Why not a house, too?

__________________________________

Excerpted From What Is A Dog?: A Memoir. Copyright © 2021 by Chloe Shaw. Excerpted by Permission of Flatiron Books, A Division of Macmillan Publishers. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.