What Jane Austen Can Teach Us About Building Suspense

How to Use Dramatic Irony and Plot Secrets

Secrets are key to Jane Austen’s fiction and to driving her narratives forward. She lived in a society where life was lived very publicly, and yet true feelings and emotions were often kept hidden. In Love and Friendship she spoofed the cult of sensibility—the characters have constant fits of fainting, weeping and running mad—but in her mature works Jane Austen demonstrated the power of keeping characters’ feelings under wraps. Mr. Darcy’s first proposal to Elizabeth is a wonderful example of suppressed feelings coming to the surface. In Chapter 34 of Pride and Prejudice he bursts out, “In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you,” sentences that can now be bought on tote bags and keyrings. Until this point Mr. Darcy has kept his feelings hidden because he thinks that Elizabeth’s family are beneath him.

In this section we’ll look at secrets and suspense in fiction, at successful plotting and the use of dramatic irony—all as important in novels and stories today as they were two hundred years ago.

At Jane Austen’s House Museum you can see the family recipe book kept by Jane’s friend Martha Lloyd. There are recipes for everything from white soup—as enjoyed at the Netherfield Ball—to “curry after the Indian manner,” apple snow (an apple meringue pudding that sounds delicious), ink, medicinal cures and household products. There’s even a pudding recipe written in rhyme by Mrs. Austen.

Jane was too busy writing to contribute much to the book; Cassandra and Martha saved her from many domestic chores. Here, instead, is a recipe for a suspenseful novel.

A RECIPE FOR A SUCCESSFUL NOVEL

Backstories

You need interesting and convincing backstories for all your characters. You’ll have to decide what to reveal to the reader and to other characters and when to reveal it. This is one of the ways to create suspense. It’s all in the revealing—a kind of dance of the seven veils of storytelling.

Think about the things that the reader and the characters do and don’t know in the early sections of your novel, and when (if ever) these things will be found out.

In Sense and Sensibility Elinor and Marianne never learn exactly how they were deprived of their inheritance but still have to cope with the realities of their new life, while Willoughby’s backstory is revealed relatively late.

In Pride and Prejudice Wickham’s backstory is also kept from the reader until later on.

In the opening of Mansfield Park the backstory of the three sisters (Lady Bertram, Mrs. Norris and Mrs. Price) sets up the plot. This establishes the themes of the novel and sets the whole story in motion.

Subplots

You need these for texture, to help build suspense and to ensure that the narrative is interesting enough and “works.” Think about how you are going to cut from one strand of your story to another, and how you are going to pull all the threads together at the end. Think about how you will use point of view, tenses and chronology, and how these will have an impact on the way the reader experiences your work. Subplots will sometimes be a way of solving problems in your main plot.

Think about the characters in your subplots and how they could be the characters in the main plot. Emma could actually have been a novel called Jane Fairfax.

But why doesn’t she just . . . ?

Your plot must be watertight, as readers will constantly question it. There should be no easy solutions. Make sure your characters’ reasons for behaving as they do are compelling. The plot of Sense and Sensibility relies on Lucy Steele’s calculation that Elinor will not disclose her secret. In a similar way, Wickham calculates that Mr. Darcy will not reveal the truth about him because of the disgrace and distress it would bring to Georgiana.

Reflections and parallels

Think about balance in your story. You can use parallel plot lines and characters to show different things and offer the reader alternative outcomes to similar situations and dilemmas. Symmetry is pleasing. Elinor and Marianne show the reader contrasting ways of viewing things and of behaving; they are paralleled by Lucy and Anne Steele. When Willoughby becomes engaged, Elinor appreciates the consequences of this for the jilted party (Marianne). Elinor wouldn’t want to be the wrecker of another woman’s happiness, not even the dreadful Lucy’s. Edward Ferrars and his siblings, the avaricious Fanny and self-centerd Robert, are also contrasted. Their attitudes to money and possessions drive the plot, and we see each character’s worth. Again and again Jane Austen gives us parallel stories and characters to compare and contrast. Think about the texture of your fiction and how using parallels and reflections might enrich it.

A METHOD

Keep your characters longing, waiting, struggling . . .

Whether you are writing a siege narrative or a quest narrative, you must keep cranking up the tension. Plots are driven by longing and desire. Think about what it is that your characters need and how this is made clear to the reader. Think about how needs and desires can be made more pressing as the story progresses. You may have to make cuts to make your work compelling enough. Check that each scene has a real function. Ask yourself what it will reveal about the characters and how it will develop the plot.

Jane Austen’s heroines are very often found waiting for news or for the arrival of other characters, particularly men. Limitations on the freedom of women were integral to Jane Austen’s plots. In Sense and Sensibility Marianne waits and waits for Willoughby to reply to her letters, while Elinor must endure to the end of the story before Edward is free to declare his love for her. In Persuasion Anne Elliot must wait to find out how Captain Wentworth feels about her and to tell him how she feels. Even after their meeting at Pemberley Mr. Darcy and Lizzy have to wait to see how each other’s feelings have changed; just when they seem about to get together, Lydia and Wickham’s elopement derails everything. Male characters have to wait too—in Sense and Sensibility Colonel Brandon has to wait for Marianne to love him—but Jane Austen’s main focus is on her heroines’ experiences and feelings.

Too much waiting and longing can, however, become boring. Make sure that you have plenty of action, humor, and constant developments to keep things moving. If the story seems to be stuck or dragging, add some sort of ticking-bomb device. In Jane’s most siege-like of narratives, Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot might marry the wrong people (Louisa Musgrove and William Elliot) if their misunderstandings continue. Something is needed to break a siege, and this something can come from the actions of one of your minor characters or from a development in one of your subplots.

Your heroines and heroes should make mistakes

To be appealing and convincing, your heroes and heroines must not be perfect; they should get things wrong from time to time. You must decide when the reader will realize that this has happened. All of Jane Austen’s heroines make mistakes, even wise, reserved Elinor Dashwood. She is happy to believe that Edward has a ring containing a lock of her hair, even though she has never given him any. This is from Chapter 18 of Sense and Sensibility.

Marianne remained thoughtfully silent, till a new object suddenly engaged her attention. She was sitting by Edward, and in taking his tea from Mrs. Dashwood, his hand passed so directly before her, as to make a ring, with a plait of hair in the centre, very conspicuous on one of his fingers.

“I never saw you wear a ring before, Edward,” she cried. “Is that Fanny’s hair? I remember her promising to give you some. But I should have thought her hair had been darker.”

Marianne spoke inconsiderately what she really felt—but when she saw how much she had pained Edward, her own vexation at her want of thought could not be surpassed by his. He coloured very deeply, and giving a momentary glance at Elinor, replied, “Yes; it is my sister’s hair. The setting always casts a different shade on it, you know.”

Elinor had met his eye, and looked conscious likewise. That the hair was her own, she instantaneously felt as well satisfied as Marianne; the only difference in their conclusions was, that what Marianne considered as a free gift from her sister, Elinor was conscious must have been procured by some theft or contrivance unknown to herself. She was not in a humour, however, to regard it as an affront, and affecting to take no notice of what passed, by instantly talking of something else, she internally resolved henceforward to catch every opportunity of eyeing the hair, and satisfying herself, beyond all doubt, that it was exactly the shade of her own.

Elinor realizes her mistake in Chapter 22.

“Writing to each other,” said Lucy, returning the letter into her pocket, “is the only comfort we have in such long separations. Yes, I have one other comfort in his picture; but poor Edward has not even that. If he had but my picture, he says he should be easy. I gave him a lock of my hair set in a ring when he was at Longstaple last, and that was some comfort to him, he said, but not equal to a picture. Perhaps you might notice the ring when you saw him?”

“I did,” said Elinor, with a composure of voice, under which was concealed an emotion and distress beyond anything she had ever felt before. She was mortified, shocked, confounded.

Secrets, irony, drama and revelations

Limiting what characters know and creating layers of irony helps to build towards dramatic scenes when things are revealed. Because Elinor is so restrained, the moments when she does reveal or discover things are particularly potent and moving. When she has the sorry task of telling

Marianne that Edward and Lucy’s engagement has been discovered and that they are to marry, she is provoked into finally expressing her feelings.

“For four months, Marianne, I have had all this hanging on my mind, without being at liberty to speak of it to a single creature; knowing that it would make you and my mother most unhappy whenever it were explained to you, yet unable to prepare you for it in the least.—It was told me,—it was in a manner forced on me by the very person herself, whose prior engagement ruined all my prospects; and told me, as I thought, with triumph.—

This person’s suspicions, therefore, I have had to oppose, by endeavouring to appear indifferent where I have been most deeply interested;—and it has not been only once;—I have had her hopes and exultation to listen to again and again.—I have known myself to be divided from Edward forever, without hearing one circumstance that could make me less desire the connection.—Nothing has proved him unworthy; nor has anything declared him indifferent to me.—I have had to contend against the unkindness of his sister, and the insolence of his mother; and have suffered the punishment of an attachment, without enjoying its advantages.—And all this has been going on at a time when, as you too well know, it has not been my only unhappiness.—If you can think me capable of ever feeling—surely you may suppose that I have suffered now. The composure of mind with which I have brought myself at present to consider the matter, the consolation that I have been willing to admit, have been the effect of constant and painful exertion;—they did not spring up of themselves;—they did not occur to relieve my spirits at first.—No, Marianne. Then, if I had not been bound to silence, perhaps nothing could have kept me entirely—not even what I owed to my dearest friends—from openly shewing that I was very unhappy.”

Marianne was quite subdued.—

“Oh! Elinor,” she cried, “you have made me hate myself forever. How barbarous have I been to you!—you, who have been my only comfort, who have borne with me in all my misery, who have seemed to be only suffering for me!—Is this my gratitude!—Is this the only return I can make you? Because your merit cries out upon myself, I have been trying to do it away.”

The tenderest caresses followed this confession.

It is so typical of the unreformed Marianne that hearing of Elinor’s unhappiness makes her speak more about herself. This isn’t about you, Marianne! And then the irony when John Dashwood bemoans Edward’s unlucky fate—being disinherited and seeing all that should be his being given to a sibling…

“It is a melancholy consideration. Born to the prospect of such affluence! I cannot conceive a situation more deplorable. The interest of two thousand pounds—how can a man live on it? [. . .]

“Can anything be more galling to the spirit of a man,” continued John, “than to see his younger brother in possession of an estate which might have been his own? Poor Edward! I feel for him sincerely.”

When it looks as though things can’t get any worse, they should

Ensure that even when your hero or heroine seems to have hit rock bottom, there is still further to fall. In Sense and Sensibility, even when the worst has happened—Edward and Lucy’s engagement is public; Edward has been disinherited in favor of his brother and is still too honorable to jilt Lucy—things get even worse. Colonel Brandon, acting out of kindness and thinking that he is helping a friend of Elinor’s, offers Edward a living so that he and Lucy can get married. Poor Elinor has to carry news of the offer to Edward and knows that when he accepts, he and Lucy will be living very close to Barton Cottage. She will be tortured for the rest of her life.

And finally you’ll need an ending

Sense and Sensibility works like a Shakespearean comedy in that everything must be untangled. Think about how loose threads are dealt with in your novel. You may want to get everybody back onstage for the penultimate or final scene.

Close to the end of Sense and Sensibility we discover the truth about Willoughby’s feelings, why he acted as he did and what his future holds. In Pride and Prejudice we learn that Wickham will never be received at Pemberley; Jane and Mr. Bingley will move to be nearer the Darcys, and we are shown the futures of all the other important characters. Here are parts of the final chapter.

Mr. Bennet missed his second daughter exceedingly; his affection for her drew him oftener from home than anything else could do. He delighted in going to Pemberley, especially when he was least expected. [. . .]

Kitty, to her very material advantage, spent the chief of her time with her two elder sisters. In society so superior to what she had generally known, her improvement was great. She was not of so ungovernable a temper as Lydia; and, removed from the influence of Lydia’s example, she became, by proper attention and management, less irritable, less ignorant, and less insipid. [. . .]

Mary was the only daughter who remained at home; and she was necessarily drawn from the pursuit of accomplishments by Mrs. Bennet’s being quite unable to sit alone. Mary was obliged to mix more with the world, but she could still moralize over every morning visit; and as she was no longer mortified by comparisons between her sisters’ beauty and her own, it was suspected by her father that she submitted to the change without much reluctance. [. . .]

Miss Bingley was very deeply mortified by Darcy’s marriage; but as she thought it advisable to retain the right of visiting at Pemberley, she dropt all her resentment; was fonder than ever of Georgiana, almost as attentive to Darcy as heretofore, and paid off every arrear of civility to Elizabeth.

Pemberley was now Georgiana’s home; and the attachment of the sisters was exactly what Darcy had hoped to see. [. . .]

Lady Catherine was extremely indignant on the marriage of her nephew; and as she gave way to all the genuine frankness of her character in her reply to the letter which announced its arrangement, she sent him language so very abusive, especially of Elizabeth, that for some time all intercourse was at an end. But at length, by Elizabeth’s persuasion, he was prevailed on to overlook the offence, and seek a reconciliation; and, after a little further resistance on the part of his aunt, her resentment gave way, either to her affection for him, or her curiosity to see how his wife conducted herself; and she condescended to wait on them at Pemberley, in spite of that pollution which its woods had received, not merely from the presence of such a mistress, but the visits of her uncle and aunt from the city.

With the Gardiners, they were always on the most intimate terms. Darcy, as well as Elizabeth, really loved them; and they were both ever sensible of the warmest gratitude towards the persons who, by bringing her into Derbyshire, had been the means of uniting them.

THE END

This is from the final chapter of Sense and Sensibility.

Colonel Brandon was now as happy, as all those who best loved him, believed he deserved to be;—in Marianne he was consoled for every past affliction;—her regard and her society restored his mind to animation, and his spirits to cheerfulness; and that Marianne found her own happiness in forming his, was equally the persuasion and delight of each observing friend. Marianne could never love by halves; and her whole heart became, in time, as much devoted to her husband, as it had once been to Willoughby.

Willoughby could not hear of her marriage without a pang; and his punishment was soon afterwards complete in the voluntary forgiveness of Mrs. Smith, who, by stating his marriage with a woman of character, as the source of her clemency, gave him reason for believing, that had he behaved with honour towards Marianne, he might at once have been happy and rich. That his repentance of misconduct, which thus brought its own punishment, was sincere, need not be doubted;—nor that he long thought of Colonel Brandon with envy, and of Marianne with regret. But that he was forever inconsolable—that he fled from society, or contracted an habitual gloom of temper, or died of a broken heart, must not be depended on—for he did neither. He lived to exert, and frequently to enjoy himself. His wife was not always out of humour, nor his home always uncomfortable; and in his breed of horses and dogs, and in sporting of every kind, he found no inconsiderable degree of domestic felicity.

For Marianne, however—in spite of his incivility in surviving her loss—he always retained that decided regard which interested him in everything that befell her, and made her his secret standard of perfection in woman;—and many a rising beauty would be slighted by him in after-days as bearing no comparison with Mrs. Brandon.

Mrs. Dashwood was prudent enough to remain at the cottage, without attempting a removal to Delaford; and fortunately for Sir John and Mrs. Jennings, when Marianne was taken from them, Margaret had reached an age highly suitable for dancing, and not very ineligible for being supposed to have a lover.

Between Barton and Delaford, there was that constant communication which strong family affection would naturally dictate; and among the merits and the happiness of Elinor and Marianne, let it not be ranked as the least considerable, that though sisters, and living almost within sight of each other, they could live without disagreement between themselves, or producing coolness between their husbands.

THE END

The sentence “Marianne could never love by halves; and her whole heart became, in time, as much devoted to her husband, as it had once been to Willoughby” is particularly interesting. The “in time” implies volumes. Is it a disappointment that Marianne ends up with kind, devoted, rich, adoring Colonel Brandon? Has Marianne lost something by marrying him? Having a husband twenty years one’s senior wasn’t unusual at that time, as so many women (and first wives) died in childbirth. Marianne, like Louisa Musgrove, has emerged more sober and serious from her illness, but the ending is nuanced and leaves the reader with some interesting things to ponder.

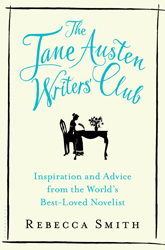

From THE JANE AUSTEN WRITERS’ CLUB. Used with Permission of Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2016 by Rebecca Smith.

Rebecca Smith

Rebecca Smith is the author of three novels published by Bloomsbury: The Bluebird Café (2001) Happy Birthday and All That (2003) and A Bit of Earth (2006). Barbara Trapido called her "the perfect English miniaturist." She is is Jane Austen's great great great great great niece.