What It Means To Be a Southern Chef As An Indian Immigrant

Vishwesh Bhatt on Marrying the Flavors of South Asia With Those of the American South

I can’t remember ever thinking to myself or telling anyone that I wanted to be a cook, and yet now that I look back, it seems that cooking and feeding people was what I was supposed to do all along.

I grew up in a very large family in the state of Gujarat, India. My mother was the oldest of eight children, and my father is the oldest of twelve. Both of my grandfathers were bureaucrats and were able to provide a reasonably good living for their families. Unfortunately, they both died early, leaving behind very little in terms of money for my grandmothers. Both women were strong, resourceful, and determined. They raised their broods to be successful and instilled in them a sense of family that has held us together for three generations. Since my parents were the oldest siblings in their respective families, they became de facto caretakers of their younger sisters and brothers, who came to live with us while they attended school in the city of Ahmedabad, where my father worked as a physicist.

I remember our house always being full. At one time, when I was six or seven, we had eleven people living in our three-bedroom flat. This meant that there was always a large crowd at the table and Mom, who was an excellent cook, was always busy in her kitchen. Each day for lunch, our biggest meal, mom prepared a thali—a meal made up of many small dishes.

There would usually be two lentil or bean dishes such as dal, at least two cooked vegetables, a raw vegetable like shredded carrots or sliced radishes, raita, something crispy like chickpea chips, and something sweet like semolina halvah or sweetened yogurt. She would put out pickles and chutneys for everyone to help themselves, and she would roll out fresh chapatis as everyone ate. After that, she’d turn around and make dinner—usually just one or two dishes. Everything we ate was vegetarian. She took pride in knowing that we ate well because she made nearly all of our food from scratch, by herself.

I want the food of my childhood, the flavors I grew up with, to become a part of the Southern culinary repertoire

Being the youngest, I was home more than anyone else and always around my mother in the afternoons while she was cooking. In order to keep me occupied and out of her way as she worked through her long list of daily chores, Mom would give me tasks to do. At first, these were simple things like setting the table, handing her utensils, measuring a portion of rice into a pot, and so on. As time went on, the assignments got more involved. She would let me add salt to the dal, measure out spices for the stew, start yogurt for the following day, churn buttermilk, and eventually chop vegetables and put the pressure cooker on. Without knowing it at the time, I was learning how to cook—and really enjoying it.

My dad had a good job, but with so many mouths to feed, his salary didn’t stretch far enough for us to have a lot of extras. We had neither a television nor a car. We didn’t buy new clothes very often, and we didn’t go on big vacations. Trips to the movie theater, for instance, were special events that included the whole family. During the holidays, we always went to one of my grandmother’s houses. Needless to say, we were a crowd. My mother, as usual, would be in charge of the kitchen, Dad would be responsible for getting groceries, and I would inevitably be in the middle of it all.

I loved going to the market with my father. I still do. When I was small, he would take me every Sunday to the main Municipal Vegetable Market in the old walled city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city. In those days, Ahmedabad was a progressive city; it had been so since its inception. That was the reason Gandhi had established his ashram and started his fight for India’s independence from there. The merchants and mill owners who were the financial backbone of the city had invested in education and infrastructure. That was top among the many reasons young, talented professionals like my father had moved there.

Dad and I would ride the bus from the suburb where I grew up to the old city. We would carry empty canvas bags for groceries and talk on the ride in. We would talk about my school, or cricket, or politics, or a book that he was reading or one that he wanted me to read. As the bus wound its way through the city, he would point out some of the historic monuments left behind by the old rulers and show me the new ones, designed by the likes of Doshi, Le Corbusier, and Louis Kahn, that were springing up.

As we crossed the Sabarmati River, he would talk about floods and famine and how the river affected the daily lives of the people who lived by it. Once we got to the market, he would talk to me about the vegetables and fruits we were going to buy. He would explain, very patiently, why we couldn’t get mangoes at the market in October or why we should buy the small squashes that day because they wouldn’t be around the following week. He would, as he still does, meticulously pick out okra one pod at a time, ask for fresh ginger from the back, ask which part of the district the guavas were from.

Without fail, he would inquire about the vendors’ families and how the rains had affected their crops. We would fill our sacks with produce, then repeat the process at the spice market, the dry goods market, and the grain market. Finally, we would sit and eat ice cream before hiring an auto rickshaw for the ride home. The rickshaw was my once-a-week luxury. It felt good to be chauffeured home.

I realized many years later that these weekly trips to the market with Dad had taught me about the seasonality of produce. They had taught me that there were real people growing the things we ate, and that it was hard work to do what they did. I had learned, without knowing it at the time, to respect farmers. And I had developed a knowledge of vegetables that serves me well to this day.

As soon as we returned home from the market on Sundays, my aunts and uncles would get to work on supper. Sundays, you see, were Mom’s day off. The “kids” would put together a meal of various items, or sometimes a big pot of an experimental dish that they were very proud of. We would sit down and eat as a family—all of us. There would be talk of politics and history, cricket, the new play at Tagore Hall, the new exhibit at Hutheesing Gallery, an upcoming wedding or funeral. There was always music: a radio show or a jazz record or the new Beatles album, or just singing from various members of the family. We would always end the evening with devotionals that we sang as a family. It was, I suppose, our way of saying thanks for everything we had.

I am the happiest when I can sit down with friends and family at a meal.

I tell you this not because I think we did anything special as a family, but to make you understand how meaningful cooking and sharing food are to me. I love to cook. I love to eat even more. But more than anything else, I love to share food. I am the happiest when I can sit down with friends and family at a meal. By extension, it makes me gratified to see a restaurant full of people enjoying the food that I have had a hand in making

*

Recently, someone important asked me if I consider myself a Southern chef. The answer is absolutely yes. I know that I wasn’t born here, but this is where I have made my home, and this is where I make my living. My food, while very much influenced by my childhood in India, is my interpretation of the way we eat here in the American South. I use ingredients and techniques I have learned from Southern chefs. I grew up vegetarian, so everything I know about cooking meat or fish I learned from watching folks like John Currence, Ben Barker, and Ashley Christensen, some of the South’s best chefs.

They have patiently answered questions and have graciously taught me the difference between redfish and red snapper. They have generously shared their whiskey along with stories of their upbringing and their families. What I have learned from spending time with some of the best culinary minds in the country is that the traditions and values I was brought up with in Gujarat aren’t that different from the ones they grew up with in places like Virginia, Kentucky, Texas, and Louisiana.

When they talk about benne seed oil pressed in South Carolina, I am reminded of the times my grandmother would send me down to the local mill with the first sesame seeds of the season to get them pressed into oil. I remember the smell and taste of that freshly pressed warm oil. I remember how my grandmother would take the pomace left from pressing and cook it with jaggery to make halvah. When I hear the excitement in my fellow chefs’ voices about sourcing raw milk, I remember the dairy farmer who would come to our house with his canister full of fresh buffalo milk, which my mother would boil to sterilize.

When I hear two chefs discuss the virtues of Virginia peanuts over Georgia ones, I remember my father talking with his brothers about why he likes the peanuts from Bharuch more than the ones from Surendranagar. When there is a debate about Carolina Gold rice versus Louisiana Popcorn rice, I remember being taught by my mother that basmati rice is good for pilafs, but that the Sona Masoori varietal from the south of India is better for use in khichadi. I grew up eating okra, black-eyed peas, fresh tomatoes, and lima beans. I grew up drinking fresh sugarcane juice and “sun” tea over ice. Peanuts remain a staple in our kitchens. Cotton and tobacco fields still stretch to the horizon in many parts of Gujarat. As long as I’ve lived in the South, I’ve felt at home at the table and in the kitchen.

I want the food of my childhood, the flavors I grew up with, to become a part of the Southern culinary repertoire—just like tamales, lasagna, and kibbeh have become. I want to show that the ingredients of the modern Southern pantry were very much the ingredients of my mother’s pantry as well. I want to tell you my Southern story the best way I know how: through my food.

___________________________________

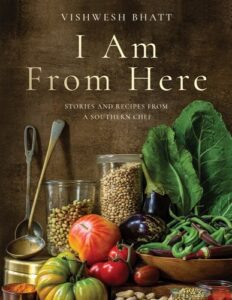

Excerpted from I Am From Here: Stories and Recipes from a Southern Chef by Vishwesh Bhatt. Copyright © 2022. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.

Vishwesh Bhatt

A native of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, Vishwesh Bhatt has made his home in Oxford, Mississippi, for more than twenty years. As the executive chef of Snackbar, where he has cooked for the last twelve years, he was nominated for People’s Best New Chef by Food & Wine and won the 2019 James Beard Award for Best Chef: South.