What is This Music? “Drill Isn’t a Genre, It’s an Aesthetic Stance.”

Kit Mackintosh Goes Deep into the Sub-Culture of Brooklyn Drill

Shimmering amid swelling, celestial strings, an angel sings. Its voice quivers, shivers and then pirouettes before retreating back into a thick mist of reverb. As the track progresses it becomes hard to discern what exactly you’re hearing. Listening to the drums you might say it was UK drill—you can certainly hear some of the genre’s fidgety rhythmic intricacy in there—but it’s not that straightforward. There are these big, clunky claps that aren’t as nimble as the rhythms in UK drill; they’ve almost got a lumbering stadium rock quality to them. You also have those strings that are at once wistful and triumphant. They’re far too expansive—far too Hollywood-scope—for the sombre solipsism of modern British street music. Once you hear the vocals it’s clear this music definitely isn’t British.

They’re American and a little Quavo-esque with all that Auto-Tune and vocal reverb, except the rap’s fractured rhythms are delivered with the frightening, cut-and-paste aesthetic of a ransom letter, it’s just not Quavo’s style—the vocal psychedelia’s too grounded. So, what is the music then?

Well, it’s “Invincible”, the opening to Pop Smoke’s magnum opus, the mixtape Meet the Woo 2. The track is a mission statement. It announces Brooklyn drill as a powerful sound in its own right, irrespective of its British and Chicago namesakes. Just the title alone, “Invincible”, clues you into the fact that the genre doesn’t share UK drill’s fixation with death-wish street defeatism, it’s full of an audible bravado that leaps out of its bombastic beats and rowdy vocal performances. As Pop Smoke’s name indicates, the music pops—it’s punchy, not placid—and it’s been far more successful than UK drill in becoming actual pop music too.

There’s an infectious aspiration in Brooklyn drill tracks, an implacable hunger to succeed that you absorb as a listener. This drive to strive and be larger than life comes across in the genre’s embrace of frag rap’s cosmic sonic frills. Artists use Auto-Tune and gargantuan reverbs in the same way as Migos do: to make themselves sound like gods. Unlike UK drill artists, for Brooklyn rappers, stratospheric status is attainable. Pop Smoke was actually able to go toe-to-toe with certified superstars in tracks alongside Travis Scott (on “Gatti”) and Quavo (“Shake the Room”).

Chicago drill and UK drill didn’t share much in common sonically but they were kindred in their attitudes and psychology.Brooklyn drill has taken the two modes of “street” in the 2010s—UK drill and the orchestral trap of Lex Luger/Chicago drill from earlier in the decade—and reimagined them through the dematerialized lens of frag rap. Unlike those used on old Lex Luger trap tracks, Brooklyn drill’s strings—heard on Lil Tjay’s “Zoo York,” for example—are floating and foggy, not aggressive and aggravated. UK drill’s drums nicked at the skin by foregrounding the restless syncopation in their rhythms, but the ghost notes in Brooklyn drill have been hushed so they sound like a distant shuffling of rustling papers more than they do barbed wire wrapped around your eardrums. The carni flows favored by British rappers give way in Brooklyn drill to fragmented vocal snippets and flickers—as in Fivio Foreign’s “Big Drip,” “Demons & Goblins” and “2 Cars”—which are then vaporized to become otherworldly bursts of reverb-drenched interstellar cloud on tracks like Pop Smoke’s “Christopher Walking.”

There was a recessive gene in UK drill, traces of something mystical in the music that never truly manifested, which can be heard in its toe-curling bass sounds, its seraphic reverbs and its general mantra-like repetition. But with Brooklyn drill these have been bought to the fore. The genre sparkles with something more magical than its British counterpart. UK drill’s coiling bass becomes serpentine in Brooklyn drill. Its cathedral reverbs are re-contextualized as hallowed and heavenly next to the dragon-scale Auto-Tune and spectral vocal interjections.

With Brooklyn drill really you’re torn between two separate realities. You’re there with one foot through the inter-dimensional portal and one firmly cemented to concrete streets. Pop Smoke’s rapping is earthy and growling, but his selection of soundscapes is in keeping with his name, it’s suitably smoggy. Listening to the aeriform organs on “War” you’re consumed by amorphous immateriality.

*

Drill, in its broadest sense, isn’t a proper genre, it’s an aesthetic stance. It’s an urge to return to documentarian street reality during a decade when rap became increasingly fantastical. An audible Rorschach test that various locales read entirely different sounds into. Chicago drill and UK drill didn’t share much in common sonically but they were kindred in their attitudes and psychology. In that respect drill is Darwinian, not just in its “survival of the fittest” outlook, but in the way it resembles a lifeform adapting and evolving to changing environments and circumstances.

Chicago drill was merely the common ancestor of these diverse set of sound-species. Brooklyn drill—contrary to its borough-specific name—arose from two transatlantic cultures interacting online: American rappers using UK beats. At first glance, this kind of Internet-driven globalization of ideas is worrying; you can’t shake the feeling that it’ll ultimately result in the emergence of a drab, homogenized global monoculture. There’s a fear that all the world’s fascinating sub-cultures—in all their glorious distinctiveness—are going to be completely diluted as they’re engulfed and ensnared in the Internet, to the point where you can’t recognize one from another.

Luckily drill has shown that global interconnectivity can actually have an invigorating effect on music and relatively regionalized scenes. Through the Internet, drill has traversed the globe, but it’s been completely reimagined upon coming in to contact with different people in different locations. The variety of drill genres that have emerged diverge from one another sonically, socially and in the psychological outlooks they inspire. They’re informed by the differing sensibilities—music tastes, senses of humor—and circumstances that are found across the world. The incentive structures for an artist in Brooklyn, for example, are completely different to those for a rapper in Brixton. There’s a real path to stardom informing almost everything about Brooklyn drill, which in turn makes it completely unique. For a whole two decades New York rap had been pretty much moribund, at least in terms of being an innovative force, but drill has revived and revitalized the music coming from the city, putting the Big Apple back on rap’s musical map.

__________________________________

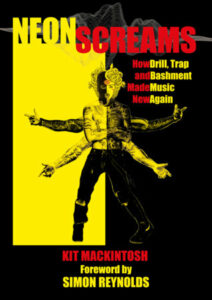

Excerpted from Neon Screams by Kit Mackintosh. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Repeater Books. Copyright © 2021 by Kit Mackintosh.