What is the Project of

Trans Poetics Now?

Editors Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel on Moving Towards

a Revolutionary Practice

We’re writing at a juncture of crisis—of longstanding roots and rapid progression, deeply embedded in economy and ecology and palpably felt at the level of everyday life. We’re also writing in a moment of revivified theory and practice against capital and empire, characterized by widespread strikes and insurrections, an international prison abolitionist movement, the legacies of Occupy and Black Lives Matter, anti-pipeline blockades led by indigenous water and land protectors at Standing Rock and Wet’suwet’en, the rediscovery by the queer and trans left of the anti-capitalist and anti-colonial politics of the gay liberation era, revitalized labor militancy, rent strikes, housing occupations, anti-fascist mobilizations, the rapid expansion of mutual aid networks and still, exhilaratingly, more.

The uprising for Black liberation that began in Minneapolis in May 2020 has further catalyzed several of these struggles, making a world without prisons or police feel suddenly like a real political possibility. Against the common-sense intuition that crisis means we must demand less, we assert with our comrades that everything has to change for anything to continue. We think of what Amiri Baraka urges in “A New Reality is Better than a New Movie!”: the “scalding scenario” called “We Want It All . . . The Whole World!” The title of this volume is therefore entirely literal. What we want is nothing other than a world in which everything belongs to everyone.

We have two perversions to offer to this comradely slogan. The first is the claim that, as trans people, we address this situation of crisis from a particular standpoint, or related series of standpoints, which inform how we think about struggle in the broader terms of left social and political movement. The struggle for gender liberation, construed broadly as a political project instead of as a narrow fight over particular rights and recognitions, touches directly on movements for ecological and climate justice, for a world without prisons and borders, for a liberatory reworking of gender and sexual relations, and for universal access to housing and healthcare.

We relate the aesthetic projects of creating alternate modes of gender and sexual life to what Kristin Ross calls the political ideal of communal luxury: the insistence that, beyond subsistence, everyone must have their share of the best. These projects of subjective liberation—of making a world for exuberant trans desire, among other modes of living—foreground bodily autonomy as an object of social and political struggle; trans people have a particular stake in a fight that, properly speaking, belongs to everyone. As a collection of writing by trans people against capital and empire, this book attempts to piece together these multiple points of overlap between the subjective, interpersonal, and everyday modes of trans life, and the internationalist horizons of the fights we are already engaged in.

We’re writing at a juncture of crisis—of longstanding roots and rapid progression, deeply embedded in economy and ecology and palpably felt at the level of everyday life.

The second is the sense that poetry bears on the project of imagining and making actual a totally inverted world. We don’t hold that poetry is a form of, or replaces, political action. Poetry isn’t revolutionary practice; poetry provides a way to inhabit revolutionary practice, to ground ourselves in our relations to ourselves and each other, to think about an unevenly miserable world and to spit in its face. We believe that poetry can do things that theory can’t, that poetry leaps into what theory tends towards. We think that poetry conjoins and extends the interventions that trans people make into our lives and bodily presence in the world, which always have an aesthetic dimension. We assert that poetry should be an activity by and for everybody.

The project of the collection that follows is therefore a gamble of sorts. Can a poetics both ground itself in a particular social identity and speak expansively towards the present and its crises? Trans poetry has typically foregrounded the body, its uses and constraints, its uneven legibility, its relations to racial and colonial modes of categorization, its conscription into the wage and the working day; what else can this emphasis render into focus? How does a trans poetry translate itself across borders and languages, or account for the colonial conditions of its own emergence? What modes, beyond and together with agitprop, are capable of forcing an encounter between the ideal and the actual? In asking these questions, we’re attempting to refuse in advance the imperative of representation that the publishing industry places on trans literature.

Since the so-called tipping point, opportunistic publishers have attempted to instrumentalize trans writing for profit; we’re asked to transform even a brutal personal experience of abjection into titillating narratives for bourgeois readers eager to consume stories of trans pain. This process more or less represents how capital turns the precarity and violence of trans lives into cultural commodities. Tourmaline, Eric A. Stanley and Johanna Burton call representation the “trap of the visual: it offers—or more accurately, it is frequently offered to us as—the primary path through which trans people might have access to livable lives.” Against the trap of representation, and against the conception of trans literature as a self-interested discourse narrowly focused on securing the rights and recognitions of the state, we aim in this volume to assemble a trans poetics that both addresses and articulates itself beyond the confines of our own lives.

We didn’t have to look far to encounter the overlap between trans poetry of the present and a writing that positions itself explicitly against empire and capital. This is surely in part because, as Ruth Jennison and Julian Murphet argue in their recent Communism and Poetry, “the resurrection of the mass action . . . has created the possibility for spatial nearness between the poet and other bodies and voices. This resuturing of poet to street has revivified the question of what poetry can do.” Poetry of the present, to a greater degree than a generation before, corresponds to the event of mass uprisings.

Poetry isn’t revolutionary practice; poetry provides a way to inhabit revolutionary practice.

On the other hand, the past decade has witnessed a groundswell of poetry by trans writers. In 2013 the editors of Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics could reasonably note their struggle even to find an overlap between poetry and trans communities. That moment has, thankfully, passed. Trans poetry has burst the banks of any narrow canon, or even the possibility of a concise and tidy canonization. And where trans poetry in the past half-decade has exploded, it has done so overwhelmingly as a writing against capital, prisons, borders, and ecocide, animated by collective and communist desires. Our aim in the present collection is therefore both to register and to amplify this tendency—to help turn the volume all the way up on what’s already going on.

At the same time, we want to link the current rise of trans radicalism to prior moments of the same, looking to the long history of queer militancy—however fraught—across social struggles and political movements. By way of illustrating this intergenerational history, and thinking through the embeddedness of poetry and activism in our lives and communities, this collection includes essays from mentors, friends and revolutionaries who’ve passed alongside contemporary trans writing: Sylvia Rivera’s “Bitch on Wheels” speech; the opening to Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues; excerpts from the writer Lou Sullivan; and an essay by the late Bryn Kelly on the vexed overlap of poetry and activism across generations of queer anti-capitalists. We’re grateful to everyone who granted permission for these texts or put us in contact with the executors of the writers’ estates. We put this work forward in conversation with that of our contemporaries, searching for a radical history for our present contexts—writing, organizing, community.

In unmaking and making a world, the poetics of this volume attempt a series of formal and linguistic experiments with political stakes. By “experiments” we mean projects that attempt a continual and creative rediscovery of their own arrangement, language, composition, and collaboration in order to stage a confrontation with a determinate moment. These experiments also disclose both senses of radical we mean to draw on, political and aesthetic. Whatever its shortcomings, we select “radical” as the word in English capable of evoking both idioms at once.

Meanwhile, we invoke poetics as a category that can combine aesthetics and politics at once, and transform the two into the formalization of a project. How can a trans poetics deploy, for instance, the techniques of collage, translation, and collaborative composition, the genres of the journal poem or the epistolary, the modes of repetition, serial composition, and direct address, the rewriting of historical or residual texts, and the declarations, excesses, and realism of the lyric? Where our sexual lives are unevenly stigmatized and criminalized, what does a pornographic writing by and for trans people look like, and what does it make possible? Where pop culture and critical theory alike have adhered to the spectacle of gender variance with a fetishizing, sadistic interest, how do trans writers creatively reply to or derange these cultural discourses? Over two decades ago, Viviane Namaste observed that “autobiography is the only discourse in which transsexuals are permitted to speak”; what poetic modes make it possible for us to speak in the first person while refusing or transmuting the force of that imperative to a singular autobiography? How does a trans poetics refute the singularity of so many private narratives and work towards forms of collective language?

These questions guided our decisions in selecting and soliciting work for the anthology. We started working on this project because, in the explosion and commodification of “trans lit,” we wanted to amplify writing by trans people against capital, prisons, and borders. The two of us overlap in several of our poetic desires and points of reference—like, Kay’s pretty sure that she and Andrea were at the David Wojnarowicz Whitney retrospective on the same day in 2018—and we also wanted to get outside of those limits, including our own aesthetic habits and our social lives grounded in large, wealthy cities in the US.

At the same time, we want to link the current rise of trans radicalism to prior moments of the same, looking to the long history of queer militancy across social struggles and political movements.

More than attempting to mirror our own tastes and formal strategies, we wanted to be surprised by a poem’s alignment of form and political imagination. We wanted to use the volume to assemble poetic work in English from writers outside of New York and the Bay. We also wanted to move past certain trans lit clichés: coming out narratives, for instance, or testimonies to the private experience of dysphoria or social rejection. Versus the sexual moralisms of the present, we wanted to read poems that state a frank and even graphic relationship to desire—that were more interested in being exuberant and real than pristinely correct. We wanted work that articulates a keen fuck you, and, even in the first-person singular, invites an imagination of collective social and political stakes.

To that end, we note several patterns of overlapping strategies and concerns that emerged in the work as a whole:

(1) A tendency to braid together ecological and anti-capitalist poetics, keenly attuned to the uneven simultaneity of environmental crisis. See Raquel Salas Rivera’s “soon we’ll be people again” or hazel avery’s “sister city.”

(2) A writing-through of historical material, using juxtaposition and rewriting to think the relation of trans identity and colonial history. Cameron Awkward-Rich’s “Everywhere We Look, There We Are,” for instance, scatters the lexicon of Doc Trimble’s arrest over the page while Rowan Powell’s “(along a line a leap a landing),” rewrites the medical history of Marie Germaine (who, according to the 16th-century medical writer Ambroise Paré, leaped over a ditch and became a man) with the history of enclosures of the English countryside and the contemporary medical regulations targeted at Caster Semenya.

(3) The serial poem patterns itself on and against the repetitions of everyday life. We look for example to Harry Josephine Giles’s “Abolish the Police” series or the excerpts of serial poems from Ian Khara Ellasante, Jesi Gaston, Laurel Uziell, and Stephen Ira.

(4) The collaborative exchange licensed by the epistolary—by letters, or messages, or poems in letters. The epistolary makes it possible to speak intimately without disclosure—making it especially appealing for trans writers, who can speak about their lives without indulging a kind of prurient or sensationalizing interest in autobiography. Exchanges between Jo Barchi and Clara Zornado, xtian w. and Anaïs Duplan, and an excerpt from Evan Kleekamp’s The Cloth enlarge a sense of the mediated intimacy and expansive thought of the trans epistolary.

(5) A palpable sense of prisons as the other side of the lyric poem’s beautiful interior life. One question we’re asking: how can poetry be a point of solidarity and collectivity between people inside and outside the system? We think of listen chen’s line: “the social shadow explodes behind every judge’s you.”

(6) An exuberant—rather than despairing—lyricism, inflected towards pleasure, rage and embodiment in excess of or counter to journalistic description. See the contributions from, for instance, Bianca Rae Messinger, Callie Gardner, Joss Barton, Nat Raha, Rocket Caleshu, Trish Salah, Valentine Conaty, and Xandria Phillips.

(7) A turn to satire and caricature, in view of the tendency, inside and outside trans communities, to understand our lives in terms of social types—the minorly famous e-girl with 1500 twitter followers, the guy who really needs you to know he’s a feminist, or a very nice landlord. See Amy Marvin’s “The First Trans Poem,” or Nora Fulton’s “suqu.”

(8) Intuiting a three-way relation between the abjection of trans embodiment, the grim process by which capital transforms the bodies of working people into commodities, and the enhancement and devastation of the body brought on by imperial war, several poems collected here inhabit an excess of viscera and disgust: Sam Ace, Aaron El Sabrout, Cyrée Jarelle Johnson, and Holly Raymond.

We could go on. Our intention with this partial and contingent list is to provide a non-exhaustive sense of some of the dynamic writing that the emergent category of trans literature has already made possible. We want everyone, everyone who wants to, to get in on it too. Every instance of these various texts and projects assembled here represents only a moment in a series of collective efforts to think about and intervene in the world we intend to win. We want it all, we want it fucking all, where all is a list for everyone to make.

Read two poems from the anthology here.

__________________________________

From We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics, edited by Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel. Used with permission of Nightboat Books.

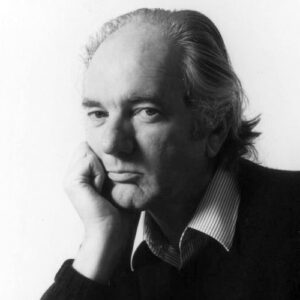

Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel

Andrea Abi-Karam is an arab-american genderqueer punk poet-performer cyborg, writing on the art of killing bros, the intricacies of cyborg bodies, trauma and delayed healing. Andrea’s debut EXTRATRANSMISSION (Kelsey Street Press, 2019), a poetic critique of the U.S. military’s role in the War on Terror, was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for Transgender Poetry. Simone White selected their second assemblage, Villainy for publication in Fall 2021 at Nightboat Books. They are a Leo, currently obsessed with queer terror and convertibles.

Kay Gabriel is a poet and essayist. She is the author of Kissing Other People or the House of Fame (Rosa Press, 2021), as well as the chapbook Elegy Department Spring / Candy Sonnets 1 (BOAAT Press, 2017). Kay has received fellowships from Lambda Literary, the Poetry Project, and Princeton University, where she recently completed her PhD. She's a member of the editorial collective for the Poetry Project Newsletter. Find her recent writing in the Brooklyn Rail, Poem-A-Day, TSQ and Social Text.