What Is It Like to Be a Black Woman in the Tech Industry?

LaTeesha Thomas Offers Chad Sanders an Insider's Perspective

LaTeesha Thomas is the CEO and cofounder of Onramp, an Oakland-based tech startup that aims to solve the technical workforce hiring crisis by helping tech giants like Google and Pandora train and hire technical talent from diverse backgrounds. LaTeesha is also a technologist, conference organizer, speaker, and advocate for diversity and inclusion in tech. Formerly she managed partnerships for Google’s Women Techmakers initiative. Before that she was director of business development at Dev Bootcamp, which was sold to Kaplan during her time there. I met LaTeesha at Dev Bootcamp. She was a colleague who became a true friend.

LaTeesha is one of very few Black women to have raised venture capital millions to run her tech startup. Less than 15 percent of venture capital funding in the US goes to women, and less than 1 percent goes to African-American and Latinx founders. LaTeesha has beaten the odds, all the while being labeled “aggressive” and “unpleasant” by micro-aggressing colleagues. In that way, her journey reminded me of Jewel’s, but Lateesha’s magic is all her own: in our conversation, she pointed to her ability to learn and master systems as the characteristic that allows her to beat the odds as an entrepreneur. And she learned how to master systems at a small, predominantly white college where she had to design her own experience to thrive.

I admire LaTeesha’s unsparing point of view on her industry. She explained that at some point her approach to dealing with a tech industry largely run by white and Asian men hardened. She won’t wait for them to change anymore, she says. She’ll work the system to take what’s theirs.

*

Chad: How did you grow up, LaTeesha?

LaTeesha: Well, I grew up in Monterrey, California. Monterrey is predominantly white and the city right next to it, Seaside, is predominantly Black. The vast majority of my family lived in Seaside. I lived in Monterrey with my mom starting in middle school. So in middle school and high school I went to majority white schools with people whose families made way more money than mine.

Less than 15 percent of venture capital funding in the US goes to women, and less than 1 percent goes to African-American and Latinx founders.

Chad: How was your educational experience?

LaTeesha: I went to a tiny liberal arts school in the middle of New England. Even though I went to a predominantly white high school, I never felt the real shock of being around white people 100 percent of the time because of my family. My school was a really tiny campus called Bard College in Simon’s Rock. There were only about 250 freshmen. Of the 250 freshmen, there were about 10 Black students on campus. I knew every single one of them and every single one of them knew me. We were all very different and weren’t necessarily friends, but it was just sort of acknowledged that we knew of each other’s presence and we understood each other’s experiences.

That was the first time I started to think about structural racism and structural inequality as a concept that was real to me. I mean, I heard things from my mom growing up, like, “You’ve gotta be five times better or ten times better, work ten times harder.” And so I understood that race played a role in my life, but it was the first time that I had a real, visceral reaction to the inequality. And that was primarily as a result of coming from a single-parent family. We didn’t have a lot of money so most of the time I couldn’t really pay to be in school. So every single semester we were just constantly behind on paying tuition. So I’d do these gymnastics with the administration to be able to register for classes on time.

As a result, I started to get more into thinking about how systems of inequalities work and ways in which I could defend myself in that system to make change. And not just that, but I also thought about how to figure out how to game the system by understanding it. I thought about how to game the system in order to create a better experience for myself. Here’s a silly example. At Bard College you could create themed housing if you wanted to try to secure better housing for yourself. You could create a theme house and have people apply to live in it. So most students might create a house specifically focused on engineering for people interested in computer programming. So we created a Black house. It was just me and my three friends who wanted to live together. We tried to call it a Black Student Union and applied for it. What were they going to tell us? No? But we really just wanted better housing for the three of us as sophomores. We applied for it and the administration was like, “We legit cannot tell these three Black women that they can’t have their fake Black Student Union–themed housing.”

So sometimes it was as silly as that. Or sometimes it was more serious. I was on a committee that worked with the deans of all the major educational programs within the school—like the heads of the science, language, and literature departments. I was elected to this committee that would approve all of the new course work and decide which courses would be taught every semester. I was able to get the school to create “Diversity Day,” which was a name I hated. But it was essentially a day where the entire school shut down classes to instead just talk about issues of race and inequality. There were different workshops and nonstructured conversations throughout the day. It was actually a pretty expensive endeavor for a school to cancel classes for a day.

Chad: So how have you applied your understanding of working through frameworks as an adult? How has that stayed with you through your professional career?

LaTeesha: I think I have just always had an understanding that I was never gonna go through the front door for anything, and so . . .

I admire LaTeesha’s unsparing point of view on her industry. She explained that at some point her approach to dealing with a tech industry largely run by white and Asian men hardened.

Chad: Because of your race?

LaTeesha: Uh, yeah, I would say that. Because of a mix of my race and my gender.

Chad: Mmhmm.

LaTeesha: Let’s take Dev Bootcamp for example. Dev Bootcamp was an immersive coding school that you and I both worked for. They had this really interesting system of management called Holacracy which was essentially a gamified way of governing groups of people in a seemingly flat, but not actually flat, company. You had to be able to understand all these rules in order to really participate in a meaningful way in the structure of the organization.

A lot of people within that organization felt really disenfranchised because they didn’t understand the rules and didn’t understand how to navigate within those rules and felt like they didn’t have a voice in what was happening within the organization. A good amount of those people who felt disenfranchised were white. And I just found it to be really funny because they don’t understand how, in the world, the system works in their favor all the time. This was the one time where they had to figure out how to navigate within this little bitty world that had been created and had been constructed. And they couldn’t do it. And they just refused to do it, because they were used to being able to operate within the systems that work for them.

But “The System” had never worked for me in any context. So when I encountered this new managerial system, instead of expecting for it to work for me, I studied and learned how to use it, and I think that was the primary reason why I was able to accumulate influence and authority within that organization. I came in as an operations manager, which was basically an officer manager role. I came in at what was one of the lowest level roles in the company and ended up as the head of partnerships and business development. In that time, I saw many people who had come in with a lot of authority leave very quickly or fall off along the way because they just couldn’t figure out how to work within that system.

I just never had that assumption that things were going to be given to me. I never assumed I would be able to just climb a normal corporate ladder and get the things I want. So, I’ve always had to take a step back to figure out how things are working. What are the complex interconnected relationships between both people and teams? How can I play that to my benefit to get the things I want within an organization?

Chad: You are a businessperson and a technologist. You know the premise of the book states that there are things we learn from enduring and experiencing Blackness in this country that can be applied to advance ourselves in business, science, art, etc. Do you believe that’s true? Why or why not?

LaTeesha: Yes I do. And I also feel it’s hard to quantify. It’s hard to describe. Business, or whatever you’re doing, is about relationships. It’s about people and how people work together and influence and power. As a Black person you have to be hyperaware in every moment of how you’re being perceived by the people around you. You have to be hyperaware of how you’re showing up in the world. And not just when you go to work, but when you’re walking down the street and having conversations with people. In order to protect yourself, to stay alive, you have to be hyperaware of how your presence is affecting other people. And not because you’ve done anything wrong, but because history has shown that people’s perceptions of you may not necessarily match the way that you see yourself or the way people who know you experience you. But sometimes those perceptions can be really powerful and sometimes those perceptions can override somebody’s logical thinking and cause them to have an emotion that could ultimately be harmful to you.

As a result, I started to get more into thinking about how systems of inequalities work and ways in which I could defend myself in that system to make change.

In being hyperaware of how you’re showing up, you develop a level of empathy that is so necessary, no matter what industry you’re in. And being able to read people and to read situations around you makes you a better leader.

In being hyperaware of how you’re showing up, I think that level of empathy is so necessary, no matter what industry you’re in. And that level of empathy makes you better at reading situations and people than most. That can help you figure out how to plug in and be helpful and be useful.

Chad: I’ve had a really close seat to watch your ascendance in the tech industry over the last, I guess . . . five years? Where do you think your drive comes from?

LaTeesha: If you had asked me this five years ago, I would have said I want to help create an industry that is more equitable and inclusive for people who look like me. And not just people who look like me, but people who don’t look like the dominant demographic in the industry. Now, instead of trying to get the industry to change, I’m far more interested in carving out spaces of my own and helping support people to carve out spaces of their own. The only way we’ll see a significant shift in the industry is by having our own large, billion-dollar unicorn companies that are Black-owned or women-run or Latinx-run. Until we start to carve out market share and compete seriously with the big companies run by white and Asian men, we’re not going to really see any significant shifts within the industry. It’s a little naive to think that we would. It’s naive to think, specifically in tech, that there would be a shift in the dynamics within an industry run by white and Asian dudes. It just seems illogical to me. And instead of getting them to change, I’m more interested in just taking what is theirs.

Chad: How would you advise a young Black person to find success in the tech startup world without sacrificing her cultural identity? Is there a way she could use that identity as a source of strength?

LaTeesha: Yeah, I don’t know. This may not be the best advice, but I am becoming better at compartmentalizing my life. I just have to realize that I’m not going to get everything I need from my work life. In order to supplement, I have to build a community around me of like-minded folks in my industry to reaffirm my experience so that when something happens to me at work, and I don’t really feel like I can speak out on it in the moment, I can go back and talk to somebody who’s had a similar experience. I have to be able to talk to someone who can say, “Yes, that happened. No, you’re not crazy. They’re probably gaslighting you, but you’re not crazy. I hear you and I see you.” That’s been really important to me.

In order to supplement, I have to build a community around me of like-minded folks in my industry to reaffirm my experience so that when something happens to me at work, and I don’t really feel like I can speak out on it in the moment, I can go back and talk to somebody who’s had a similar experience.

Your words have power but so does your silence. I’ve observed this in one of my close friends recently. She doesn’t give people any more of her revenge than she feels they deserve. Whether that means in a moment somebody has said something wild or offensive or hurtful in a meeting, they don’t deserve to see her pain. They don’t deserve to see her anger. They don’t deserve to see any part of her, and so she just doesn’t give it to them. And it’s so impressive to me. That’s not how I used to be. I used to wear my emotions on my sleeve. Even if I wasn’t saying anything, you could see on my face how I felt about a situation. Her poker face is like no one else’s. And I’ll think that she has nothing to say and then we’ll get into a separate space and she’ll unload and tell me everything that she’s thinking and feeling. She just doesn’t feel that the person deserves any part of her. So she just doesn’t give them anything.

So, I would say, figure out what it is you want to share with people and how open you want to be, and if they don’t deserve it and they haven’t earned it, then don’t give it to them. That can be really difficult. It makes you feel like sometimes you’re choking down what you’re feeling or what you’re experiencing. But that doesn’t mean you have to never let it out. It just means that you don’t have to let it out then. You’re not going to change their behavior and it’s not going to make a difference to them. But getting your experience reaffirmed by somebody else who has experienced it before can make all the difference.

__________________________________

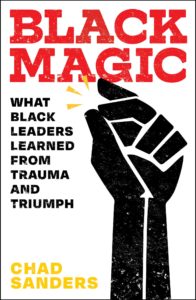

From Black Magic: What Black Leaders Learned from Trauma and Triumph by Chad Sanders. Used with the permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Chad Sanders.

Chad Sanders

Chad Sanders is the author of Black Magic: What Black Leaders Learned from Trauma and Triumph. He is the host of the Yearbook podcast on the Armchair Expert network and the Audible Originals podcast, Direct Deposit. Chad’s work has been featured in The New York Times, Time, Fortune, Forbes, Deadline, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. Chad has also written for TV series on Max and Freeform. Chad was raised in Silver Spring, Maryland, and earned his BA in English at Morehouse College. He lives in New York City.