What I Learned About Myself and the Natural World by Swimming with Sharks

Ross Frylinck on the Mysterious Allure of Marine Life

Once again, I was standing on a rocky shelf preparing to plunge into the sea. I had to laugh at myself as I stood there, about to get cold and scared again through no one’s fault but my own. At least the sun was shining and the water looked a bit more inviting. Craig asked me if I wanted to try some Tummo breathing to warm up, and he demonstrated a kind of hyperventilation technique that looked a lot like the yogic Breath of Fire. I had heard of the Tummo monks before, and how they use this method in outdoor nighttime contests in the Himalayas to see who could dry the most frozen sheets before dawn. We all did a few cycles of this breathing and I tried to imagine a flame igniting in my chest, with no success at all.

Feeling a bit dizzy and no warmer, I rested for a while on the slippery rocks until my breath returned to normal. Craig and Danny timed their jump with the surge and were quickly carried away. I caught up with them and we were soon swimming through the Sea Forest, which was lit in a golden glow by the low angle of the sun. We kept moving, weaving our way through tall stands of kelp. In patches it was very dense, and I had to push and pull my way through the thick golden fronds to make progress. Tired of this struggle, I dived down and swam centimeters above the seabed, enjoying the beautiful coralline and Ralfsia algae that covered the reef. A psychedelic play of light filtered through the canopy and danced on the neon urchins and sea stars. I saw a large, beautifully patterned super rockfish lying in a patch of Sargassum weed, and it watched me intently with its yellow bug eyes as I passed by.

Not far from the shore, in shallow water, we came upon a pyjama catshark. It was swimming snakelike through the kelp and, small as it was, it radiated power. Craig and Danny swam down next to it and Craig gently touched it on the “nose.” The shark stopped swimming and lay relaxed in his hands. I had seen catsharks sleeping in caves before when I was a child, and had sometimes surprised them when I stuck my arm into a dark hole to feel for crayfish. It was always a shocking experience and I was wary of their sharp teeth. I had no idea they could be touched, but this shark seemed as tame as a puppy. Craig passed it to me and, because I was underwater with a snorkel in my mouth, I couldn’t protest.

Gingerly I took the shark in my arms, holding it well away from my face. It lay there, looking up at me with its remarkable eyes. I stared into them for a while and was utterly transfixed. It felt like I was looking from space into a storm system blazing on the surface of an alien planet. How could such a simple animal have eyes like this? When I let the shark go, it curled up in a ball and sank slowly down to the ocean bed, where it landed, uncurled itself and swam away. We followed it back to its den, where we found a small cave that was packed with sharks. They were all fast asleep, breathing slowly and rhythmically.

I seemed to have missed the main lesson of thousands of years of civilization: Don’t get eaten by a wild beast.

Moving on, we crossed a large area of ribbed white sand where the kelp doesn’t grow. I felt uncomfortable in this openness, but at least the water was very clean, which is a relief when you are scanning for predators. Soon we came to the edge of the Sea Forest and looked into the vastness of the open ocean. It’s a liminal space, and hovering there I felt the pressure of the blue emptiness beyond. As I swam, I focused on my stroke and stared straight down to the ocean bed, which was at least 20 meters (65 ft) away. The trunklike kelp stipes in this deep water were long, sparse, and ghostly, and I watched large shoals of fish hovering in tall columns beneath me as I passed by. Feeling a familiar sense of anxiety about what might have been lurking beyond my sight, I comforted myself with the fact that shark attacks are rare, even in False Bay, which has one of the largest great white shark populations in the world. It therefore came as a nasty shock when, a few moments later, I heard a desperate scream of “Shark!” from behind me.

I spun around and saw that Danny’s face was drained of blood. I swam over to him and listened in horror as he told me that a huge white shark had just glided past, only five meters (16 ft) away from me. Three things stunned him: how it had watched me very carefully, that it didn’t move a muscle when it passed by, and that it was deathly silent. He then told me that the shark had swum toward Craig, who was about 30 meters (100 ft) ahead of us.

We quickly caught up with Craig and told him what had happened. Having asked Danny a few questions about the shark’s eyes and body language, he concluded that we weren’t in any danger. Because of his experience in free-diving with white sharks, he believed he knew how to read their body language and was relaxed about the situation. I wasn’t convinced.

Hanging on to the edge of the forest and peering into the abyss, I strained my eyes to see what was out there. Danny kept mumbling that the shark made no noise at all. An awful image appeared in my mind: a teenage surfer had been bitten in half the previous summer at a surf spot I loved, and someone had unthinkingly sent me a picture of the severed torso lying washed up on the beach. It stood for everything I feared about the unforgiving force of nature.

Craig, however, seemed genuinely disappointed that the shark wasn’t returning, and kept saying what an unbelievable privilege it would be to dive with the animal. He implored us to stay and see if the shark would return, and because I was even more scared of swimming back to shore on my own, I had to agree. We waited for a while, as I got colder and more miserable. Eventually Craig decided that the shark had gone, and we swam back to land.

Back on the beach, I was overcome with relief. Craig, however, seemed agitated, even upset, that we hadn’t seen the shark. Again, he spoke about what a privilege it would have been to swim with it, a real once-in-a-lifetime experience. He lamented that there are more Bengal tigers than white sharks left on the planet, and repeated how unlucky we were. I told him that I thought it was a privilege not to be devoured. Danny didn’t say much. I guessed he was still in shock and probably more in my camp.

I thought about the white shark and Craig a lot in the following days. I had conflicting, troubling thoughts about the whole episode. For a start, I was shaken by Craig’s recklessness and by my naiveté in following him so blindly. Was it wise to take such risks? When I told the story to my friends, they laughed at me and said I was mad to swim in False Bay. I felt that I should have known better, especially now that I was a father. What if Craig had gotten it wrong and the shark had come back and attacked me? I seemed to have missed the main lesson of thousands of years of civilization: Don’t get eaten by a wild beast.

Yet I also had to admit that I was intrigued by Craig’s unique perspective, his gift with animals, and his tolerance of the cold. It was also true that my worst fear swam past without harming me. Could it have been a warning? Or was it an initiation and an invitation to continue diving with Craig? I wasn’t sure. But I noticed that a kind of current was waking up in me, and that the other end of it was attached to Craig and the Cape Peninsula—whether I liked it or not.

__________________________________

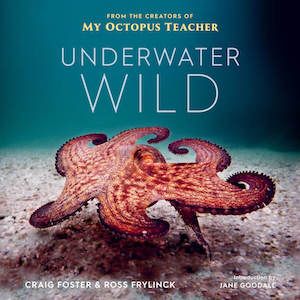

Excerpted from Underwater Wild: My Octopus Teacher’s Extraordinary World. Used with the permission of the publisher, Mariner Books. Copyright © 2021 by Craig Foster and Ross Frylinck.

Ross Frylinck

ROSS FRYLINCK is a co-founder of the Sea Change Project. He is also a co-founder of Autonomy, the international exhibition for sustainable mobility based in Paris. Ross is a writer and photographer, and a former commissioning editor at Cambridge University Press. He has been working for ocean conservation for the past 15 years and lives in Cape Town.