What Gods? On Writing Spirituality

in Literary Fiction

Alexander Weinstein Explains the Importance of the Sacred in Storytelling

In the summer of 1997, I was in the mountains of Sinaloa, Mexico living and studying with the Tepehuán Indians. It was the early years of what would become my lifelong pursuit of the Sacred, and I’d spent the day in a thatched-roof, waddle and daub house with the shaman’s apprentices, experiencing visions from the sacred medicine they use to communicate with the gods. During that ceremony, the palm leaves had become living architecture, folding their fronds above us like an arching gateway, creating an entrance to another dimension wherein beings encircled our flickering candles. The wind was filled with their whispering and we lay half-slumbering while the spirits came to visit. This was precisely what the ceremony was for, an opportunity to reestablish a relationship with the unseen world and to receive its medicine.

The ceremony had just ended, though the mushrooms were still working their way through me, and as we walked in the village dusk, I learned we were headed to the apprentices’ grandmother’s house. The destination caused anxiety; I come from a culture where using plant medicines is akin to drug addiction, and if you’re under the influence of psychedelics you certainly don’t visit grandparents’ houses. And yet, here was the grandmother, placing bowls of soup before us.

“We had a ceremony today,” one of the apprentices told her.

“Ah,” she said and looked at me from across the table, her eyes lit from the buzz of the hanging lightbulb. “And so? What gods did you see?”

The question startled me, asked as casually as one might ask a child what they learned in school or if they’d made friends. The truth was, I had met gods that day, though I hadn’t learned their names or identified them in this way. All I knew was that I’d encountered a plane of reality inhabited by sentient beings, a world normally invisible to my everyday consciousness, and that by crossing the threshold into their reality, I’d momentarily been able to communicate directly with the beings that inhabited that world and had gained a glimpse of a universe I hadn’t known existed.

All I knew was that I’d encountered a plane of reality inhabited by sentient beings, a world normally invisible to my everyday consciousness.

For the next twenty-three years, I would encounter this world again and again. Over the course of seven of those years, I traveled with the Huichol Indians on their sacred pilgrimages to Wirikuta, the birthplace and home of their gods, where I was repeatedly exposed not simply to a spirit-world which shares its borders with ours, but to a culture who’d learned to speak with the beings within that reality. I also met spiritual teachers at Naropa University, like Rabbi Zalman, Ram Dass, and Matthew Fox, who spoke openly about the world of the Sacred. It was, it turned out, a reality outlined in almost all of our sacred literatures.

Alongside my studies of spirituality, I was simultaneously studying fiction, and upon returning from the hammocks of the shaman’s apprentices, where parrots cawed and sprits visited as regularly as songbirds, I encountered the stories of Raymond Carver and Ernest Hemingway. It the late nineties, and we were learning to write a kind of meat-and-potatoes fiction so to emulate the Great Realists. While I certainly admired Carver’s craft, style, and concision, at that moment, I was struck by the absence of the sacred within his stories. There was no spirit-world in Carver or Hemingway’s universes, and people didn’t have mystical experiences, they had whisky and cigarettes and marriages that ended badly. The characters, in turn, were trapped within a world where the spiritual was far from the apartment walls that they found themselves living within. So, I began to look elsewhere. Where was a fiction that outlined the worlds I had encountered, a fiction that presented the spirit-world as a fundamental reality as central to the understanding of our universe as Chicago or New York was to Realism?

There were certainly poems that had no fear in using words like soul. There was non-fiction and spiritual memoir. There were hybrids such as Ishmael and Carlos Castaneda’s Don Juan novels. I could read the spiritual texts of the world, study yoga and Buddhist doctrines, explore the Tao Te Ching—which I did—but spirituality was strangely absent from nearly all of the literary fiction I encountered. I was searching for models so that I might hone my craft writing stories that portrayed a more holistic universe. Because if my aim as an author was to paint a picture of what it meant to be human, then a vital part of that totality included the spiritual. But while I could find plenty of stories and novels which posited the material world as the basis of all reality, a literature which incorporated the spirit-world seemed in short supply.

I also sensed an unspoken bias against spirituality in fiction. Spirituality didn’t seem to have the credibility or legitimacy automatically granted to other types of writing, and the inclusion of topics such as plant and animal spirits, gods and goddesses, chakras, and akashic records, seemed to carry the danger of delegitimizing my work. When I did encounter mentions of spirituality in literary fiction, it was often presented ironically—a gullible character had sought out a snake-oil shaman, a narcissist was taking yoga classes, and words like soul and spirit were used sarcastically, the characters who pursued it, often ridiculed. I worried about how I might integrate the visions I’d had of the mystical world without having my work shuffled off to the new-age aisle. All the while, I hoped to create a literature built upon the premise that its characters were not merely physical, emotional, or psychological beings, but were also, fundamentally, spiritual beings.

After all, the spiritual is deeply intertwined with our human experience. At this moment, monks in the Himalayas are reciting mantras to benefit all humankind; in sweat lodges and Sundances around the globe the sacred world is being called upon; and Amazonian curanderos are using plant medicines to interact with unseen deities, singing sacred songs to heal the ailing soul. Similarly, at this moment, there’s someone alone in their apartment lighting a candle to pray to the unseen world for health and safety; someone else is burning their ex’s love letters in a backyard firepit, hoping ritual may heal their pain; at a silent meditation retreat another is unburdening themselves from childhood wounds; and in the dim light of a bedroom, lovers look into one another’s eyes with the kind of awe usually reserved for god.

As a global civilization we are in a dance with the Sacred, a plane of existence which many cultures believe is interwoven with our perceived reality. We lean on this invisible, mystical world in countless ways, fight a rationalist battle against its existence or spend a lifetime seeking it out in ashrams, monasteries, and sacred ceremonies. Why then should literature ignore its presence so readily?

Where was a fiction that outlined the worlds I had encountered, a fiction that presented the spirit-world as a fundamental reality as central to the understanding of our universe as Chicago or New York was to Realism?

Perhaps part of the answer has to do with how we learn to tell stories. I have a theory on fairytales, that the fairytale author who wishes to write actual fairytales must spend a long time wandering the fields and groves and resting by rivers and brooks beneath willows and arching trees—must, in short, go seeking the unseen world in hopes that the unseen might decide to enchant and whisper tales of the sacred into the storyteller’s slumbering ear. Which is to say, there are stories we make up as authors from our hearts and minds, and there are other stories that are shared with our consciousness from an unseen world. While such a belief might seem strange in the Western world, it is, of course, the commonly understood role of storytelling by many societies who see stories, songs, dance, and art as human portals to an animate other world.

When I was traveling in Iceland, I had the fortune of meeting a fascinating storyteller, who had yet another take on fairytales. He believed words could make manifest the unseen world. If you wanted to see fairies, you merely needed to describe the fantasies you were imagining. “Right there, in that small icy river, you can see them playing now,” he said. “One is laughing and the other is splashing water.” The connection between stories and the invisible world was a tangible and immediate one for him. And he reminded me that we make manifest the invisible world though the very language we use, and that we help to create and sustain the sacred through stories. This is of course what all writers do. We build worlds from our imaginations, and if it is true that stories reveal our hopes, dreams, and visions of the future, then perhaps stories can also help connect us with a more mystical, transcendent, and spiritual reality.

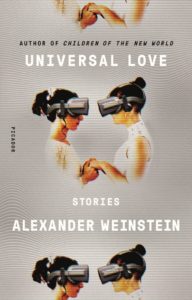

I’ve been working to capture the unseen through my fiction for the past two decades. The visions I had during my spiritual journeys are the basis for my stories in Universal Love, where the hearts of my characters and their encounters with awe, love, and compassion are the gateways to the border between the known and unknown world. As I wrote the stories, I thought about the things I hold sacred, and I gave them to my characters. Sometimes it was fatherhood, kindness, or compassion, other times it was the vulnerability of heartbreak, grief, or the nostalgia of parenthood, where one day your child is holding your hand, and the next they’re waving goodbye. And suddenly a story about holographic parents (“The Year of Nostaglia”) revealed a truth about the mystery of my own parents, and the importance of connecting deeply with the people I love.

Beneath the robots, holographic parents, and virtual-reality-landscapes of my fictional worlds, are stories of the sacred, and while my work is speculative, my stories believe in a deeply spiritual truth: that we can care for one another more deeply, that we can love one another more fully, and that we can work together to make this world a better place. Stories can contain sacred medicine, a belief which echoes the cosmologies of many of the world’s shamanic and spiritual lineages, and through my fiction I’m simultaneously trying to describe the sacred worlds that I believe exist within our shared reality, a speculative mythology built upon the spiritual.

Nearly thirty years ago, a grandmother asked me a simple question.

“What gods did you see?”

I couldn’t answer her question then, but through my stories, I’m working to answer it now.

__________________________________

Universal Love: Stories by Alexander Weinstein is available now via Picador.

Alexander Weinstein

Alexander Weinstein is the author of Children of the New World, which was named a notable book of the year by the New York Times, NPR, and Electric Literature. He is a recipient of a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award, and his stories have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and appear in Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy and Best American Experimental Writing. He is the Director of The Martha's Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing and a professor of creative writing at Siena Heights University.