What an Ecofeminist Pioneer Can Teach Us Today

On Françoise d’Eaubonne's Radical Vision

Translated by Emma Ramadan

In our opinion, there is a clear connection between the treatment of the bodies of women, the enslaved, the disabled, and the racialized, and the treatment of lands, animals, and plants: they are all naturalized terrains of experimentation or conquest.

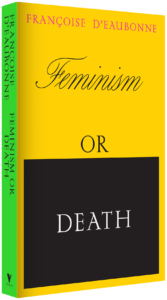

In many respects the first English translation of Feminism or Death by Françoise d’Eaubonne this year by Verso Books is indicative of the late arrival of ecofeminism in France. The rediscovery of d’Eaubonne coincides with the resurgence of ecofeminist movements around the world in response to the climate emergency. As ecofeminists, we deem that cooperative models are inherently practices that aspire to construct societies free from subordination based on gender, race, and class. Our collaboration is a response to the call of d’Eaubonne to build a bridge between theory and action.

*

Revolutionary and visionary in many respects, it is also problematic in certain ways. However, we maintain that this text needs to be accessible once more because it is illustrative of a moment in time and of a certain wave of French materialist feminism of the 1970s. To mask its gray areas would amount to perpetuating the discourse that, still today, continues to ignore the transnationality of ecofeminism and its necessary decolonial critique. Although we position ourselves in the lineage of Françoise d’Eaubonne, we distance ourselves from some of her analyses. That said, like her, we refuse to create a separation between our writing, our research, our actions, our emotions, and our lives. Ecofeminism is at the intersection of all of this, and if we want it to have a future, we must remember its past. Feminism or Death is a part of both.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Françoise d’Eaubonne was known to the general French public as a prolific author of poems, biographies, science-fiction novels, and philosophical essays. However, internationally, her reputation was not that of a simple writer: in the anglophone North, she became well known for forging the term “ecofeminism,” which she used for the first time in the final pages of her essay Feminism or Death.

D’Eaubonne advocates for the transfer of power to women, embodied by what she calls “nonpower,” or the destruction of all power.

The colossal oeuvre of this “resolute rebel” is rivaled only by her dogged revolutionary activism. When d’Eaubonne was very young, she joined the anti-Nazi resistance, then enlisted in the Communist Party. Because her involvement in these groups didn’t manage to encompass the ensemble of systemic oppressions, which she sensed was fundamental, she became involved in the Women’s Liberation Movement (MLF) and then in the Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action (FHAR). Her constant engagement nourished her writing as well as the ecofeminist activism she was developing. Drawn to environmental concerns elicited by the nuclear threat of the 1970s, her ecological awareness led her to focus on what she considered two inseparable variables: ecology and feminism.

The inextricable link between the two was indeed cruelly lacking from the analysis of the French left of the time, which positioned the class struggle as master of all oppressions. In addition, contrary to the majority of ecofeminist theorists who held positions in prestigious universities, Françoise d’Eaubonne was neither a professor nor an accredited researcher. Her schooling happened through her participation in activist movements. Reading Feminism or Death, we feel just how independent and institutionally autonomous her feminist education was. This book is also a voyage through the thoughts of an insatiable dissident living the struggle and translating it into theory without ever distancing herself from it.

Alongside her feminist comrades, d’Eaubonne would spearhead the Feminist Front, the Ecology-Feminism Movement, and the Ecology-Feminism Center—hotbeds of ecofeminist activism largely cited in international literature but whose activities are very poorly documented. Although the existence of these groups was barely noticed, their denunciation of the patriarchy was completely brazen, as evidenced by the resolution written in a 1974 pamphlet from the Ecology-Feminism association: “Down with men and their flagrantly self-destructive tendencies.” In August of the same year, the “Mouvement Écologie-Féminisme Révolutionnaire” called for a “birth strike” at the global conference on population organized by the United Nations in Bucharest. Their demands, which were certainly audacious, called for nothing less than “the total and irreversible abolition of sexism and the patriarchy.”

D’Eaubonne advocates for the transfer of power to women, embodied by what she calls “nonpower,” or the destruction of all power. To concretize this project of an egalitarian society—seductive notably for its resolutely anti-authoritarian framework—she insists on the necessity of a collective provision of the means of production, which differs from the socialism of her time that she criticizes from top to bottom but also largely echoes green anarchy and libertarian social ecology. She also promoted the “decentralization of energy” in favor of a soft “poly-energy” instead of the mass utilization of “mono-energy,” a technique that is heavy, masculine, and capitalist.

Her use of the terms “mono” and “poly” evoke the later writings of Vandana Shiva on oneness and monoculture, which, according to her, must be urgently replaced by ecofeminist approaches founded on the diversity of agricultural techniques and practices respectful of biodiversity. Finally, we can only applaud her call to dismantle both the nuclear family and the nuclear industry—components of the “same fight”—that we interpret as a direct invitation to destroy the patriarchal and heterosexual family model.

Françoise d’Eaubonne’s ecofeminist theory is thus not a juxtaposition of feminism and ecology but an analysis of the “world-system” from an angle that places the marginalized and the exploited at its center. She explains that the ecological threat that weighs on all forms of life is not only a priority but indissociable from other fights. Contrary to the emerging ecological movement at the time, she maintains that the destruction of the environment is the consequence of a phallocratic system that originates in masculine and pre-capitalist farming techniques. According to her, these techniques led to the appropriation of women’s reproductive systems and organs, resulting in overpopulation and the destruction of natural resources. That said, the author’s focus on “phallocracy” can be disconcerting. Her frequent use of the term (to which we generally prefer the term “patriarchy”) denotes an essentialization of categories typical of the radical feminism of the 1970s. But d’Eaubonne regularly evokes a non-binary vision of gender and even of sex, and goes so far as to suggest that gender is a social construction of the phallocracy.

Despite her major avant-garde contributions, d’Eaubonne’s ecofeminism was met with relative indifference in France.

Since the 1970s, feminism has interrogated the origins of patriarchy in order to better understand the roots of this societal structure. In France, debates were focused on “the woman question,” which attempted to analyze the mechanisms at the root of the subordination of women through the lens of the connection between capitalism and the patriarchy at a global scale. Among the various waves of thought that materialized at the time, d’Eaubonne’s stands out. By positing that the patriarchy led to the domination of men over women and to the devastation of nature, she not only denounces the sexist structure of society but also blames it for the destruction of the environment. Nearly a decade later, the sociologist Maria Mies would locate the roots of women’s oppression within a more ecological analysis of the “capitalist patriarchy”—a term first used by Zillah Eisenstein which explains a socioeconomic structure founded on the exploitation of not only labor but also gender.

However, despite her major avant-garde contributions, d’Eaubonne’s ecofeminism was met with relative indifference in France. If Feminism or Death seems to have aroused a certain attention in the feminist, notably Parisian, milieu upon its arrival, the term “ecofeminism” was not adopted by social justice activists or really studied by researchers. The merging of women and ecology was subject to controversy in a French feminist milieu that was predominantly materialist and virulently opposed to essentialism, which is still the primary reproach of ecofeminism in the West. In France, ecofeminism continues to provoke mistrust among our peers, as if this concept were struggling to insert itself into the landscape of contemporary feminisms. We hope, at our level, to recognize an unjustly forgotten author and reaffirm that ecofeminism has a French history.

__________________________________

Adapted from the introduction to Feminism or Death: How the Women’s Movement Can Save the Planet by Françoise d’Eaubonne, edited and translated by Ruth Hottell.

Myriam Bahaffou and Julie Gorecki

Myriam Bahaffou is a scholar and activist; her main field of research is animal ethics in an decolonial ecofeminist perspective. In France, she tries to renew the vision of the ecofeminist movement, insisting on its radicality and showing the originality of its narrations.

Julie Gorecki is an ecofeminist activist, scholar and writer. She works on new ecological feminisms towards a “feminist system change not climate change.” She is a PhD candidate at the University of California Berkeley and is also part of the transnational women and feminists for climate justice movement.