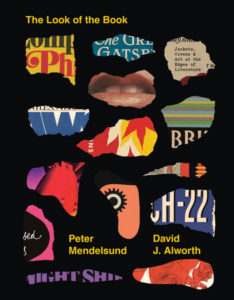

What a Book Cover Can Do

Peter Mendelsund and David J. Alworth Consider Information As Art

As a physical component of the book, the cover is a skin, a membrane, and a safeguard: paper jackets protect hardback boards from scuffing and sun damage, while paperback covers not only hold the book together but also keep its sheets clean and safe from tearing. In the past, paper jackets were plain wrappers used to shield decorative bindings, but around the turn of the 20th century, illustration migrated from the boards to the jackets themselves.

In a metaphorical sense, a book cover is also a frame around the text and a bridge between text and world. The cover functions simultaneously as an invitation to potential readers and as an entryway into the universe that the writer has created, whether fictional, historical, autobiographical, or otherwise. Come, it says, join the party—or at least save the date.

As a designed object, the book cover is a first look at the text and a visual rendering of what the text says: it is both an interpretation and a translation from verbal into visual signifiers. While the cover designer may wish to convey something original, there are constraints on the design process, since the book cover also serves as a kind of information kiosk that not only indicates author, title, and publisher but also locates the book in relation to genre.

There are well-established visual tropes for genres such as crime, science fiction, fantasy, and romance, but all books must announce their place with respect to other books. No one likes false advertising.

Books also need to sell themselves, so covers can be understood as teasers, functioning much like movie trailers, giving us just enough detail—including comments from other readers, known as “blurb” writers, whose praise is in fact promotion—to entice us to buy the book. The blurb is a standard feature of many book covers, but for nearly as long as it has been around, it has provoked suspicion, ridicule, and even scorn.

George Orwell, in 1936, blamed the novel’s decline on “the disgusting tripe that is written by the blurb-reviewers.” Camille Paglia called blurbs “absolutely appalling” in a 1991 speech.This anti-blurb tradition stretches all the way back to the inventor of the term, Gelett Burgess, who created a book jacket in 1907—featuring “Miss Melinda Blurb in the Act of Blurbing”—to mock a convention that was becoming more widespread in publishing.

There is an intimate connection between what we read and who we are, between shelves and selves.Burgess coined the term, but credit for the thing itself should go to Walt Whitman. After reading the first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855), Ralph Waldo Emerson sent the poet a letter of praise. At the time, Emerson was a prominent intellectual, whereas Whitman was relatively unknown outside New York. The letter was meant to be a private word of encouragement. Whitman had it published in the New York Tribune.

And one year later, in 1856, he had one line of the letter—“I greet you at the beginning of a great career”—stamped in gold leaf on the spine of the book’s second edition. It’s no surprise that the poet whose first great poem begins “I celebrate myself” had a flair for self-promotion.

Indeed, Whitman knew that book covers are not only advertisements for the books themselves but also advertisements for the kinds of readers we imagine ourselves as being, or would like to be. There is an intimate connection between what we read and who we are, between shelves and selves. Finish reading a book, and its cover serves as a souvenir commemorating a transportive reading experience.

Finish reading an especially difficult book, and its cover functions more like a trophy awarded for intellectual labor. Carry a book around in public, and its cover can betray you to other people who will make assumptions about you. It feels risky to be so exposed, but at times such assumptions are welcome, as when a book cover, flashed across a crowded subway car, operates like a secret handshake with another person reading the same.

A safeguard, a frame, a bridge, a translation, an interpretation, a teaser, a souvenir, a trophy, a handshake, and more—the book cover is many things. And it performs many functions. It is for this reason that we think of the book cover as a medium, whose multiple platforms (e.g., paper jacket, paperback, digital image) work together to represent the text visually and to present the book to the world.

The term “medium” has several overlapping meanings, which allows it to capture the various identities and functions of the book cover in our time. Its cognates “mediation” and “mediator” suggest processes of intervention and brokering: unhappy couples pursue divorce mediation; middle-school students can see peer mediators instead of going to the principal’s office.

Since the 16th century, “medium” has been used to discuss the middle ground, quality, degree, or condition: the state of being in between two things. For instance, in The Art of Distillation (1651)—a distant precursor to today’s home-brewing and mixology guides, with a dash of alchemy and medical science thrown in—John French describes one of his concoctions as “a saltish slime, and in taste, a Medium betwixt salt and Nitre.”

A main job of the book cover is to concretize the abstract, to visualize the ephemeral, and to render the metaphysical.At the same time, “medium” also designated any intervening substance that can carry expressions, sensations, and moods; “the air,” wrote one philosopher in 1643, “is the medium of musick and of all sounds.”

And alongside these meanings were two others: the idea of currency or the medium of exchange (e.g., any token of value used in a trading system) and the idea of the spiritual medium (e.g., a person claiming to be in contact with the dead).This last meaning is not so far-fetched, since a main job of the book cover is to concretize the abstract, to visualize the ephemeral, and to render the metaphysical.

Later, in the 19th century, “medium” began to take on the more modern meanings that we know today. On the one hand, there is the idea of a communications medium: a channel of expression or an information delivery system through which signals ow back and forth. This idea intersects with our sense of “the media” as a vast system of journalism and entertainment that includes newspapers and magazines, television, talk radio, and the internet, as well as the many people who work as content producers, editors, influencers, and pundits.

On the other hand, there is the idea of an artistic medium: painting, sculpture, dance, film, and so on. In the arts, the term refers to both the material and the mode of creation: clay or marble or papier-mâché can be considered the medium of sculpture, but sculpture, too, is a medium in its own right. And to speak of sculpture as a medium is not merely to discuss its materials, but to invoke an ancient and venerable aesthetic practice, whose meanings and values have been debated for millennia by artists, philosophers, and critics. This expansive notion of medium encompasses the histories, theories, and creative techniques of any art.

So, what does it mean to think of the book cover as a medium? It is to see the book cover as a thing-between-things, a middle ground between text and context, a zone of interaction between the writer’s vision and the culture in which the book is published.

Further, it is to see the book cover as a mediator or intermediary that testifies to the social dimension of writing—for even if manuscripts are individually authored, books are collectively made, and their covers emerge through a process that involves many interested parties, not only the author and the designer, but also the editor, the publisher, the marketing director, the printer, and more.

Carry a book around in public, and its cover can betray you to other people who will make assumptions about you.Covers demand collaboration; the design process involves iteration, feedback, and revision. The end result is the production of an information-rich medium and, perhaps, also a work of art.

To be sure, most book covers are not works of art, but commodity packages. Nearly all book covers, however, are mixed-media productions that combine verbal and visual elements. Marshall McLuhan tells us that “the ‘content’ of any medium is always another medium,” and this claim seems especially apt for the book cover, which recycles drawings, photographs, and text from book reviews and other sources.

Take, for instance, the cover of Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016). Its original design was revised to include unexpected praise from Ta-Nehisi Coates—“Homegoing is an inspiration”—which Coates had issued via tweet. This is a perfect example of what McLuhan means, and it also shows us how the book cover, in the 21st century, exists both within and alongside the digital environment.

Another example is Claudia Rankine’s Citizen (2014), whose cover presents a photograph of a wall sculpture—David Hammons’s In the Hood (1993)—that invokes the history of lynching. Here, an artwork is displayed via photography as part of an overall visual design.

McLuhan’s claim draws our attention to remediation—the process whereby one medium cannibalizes another—which never ceases in a digital culture of endless sharing and remixing. The book cover plays a role in this process as both vehicle for and object in it. (This is one of the reasons why the book cover matters today.) A highly political work of art that addresses racism in America, Citizen itself was remediated in an apparent act of protest leading up to the 2016 US presidential election.

Frustrated by the remarks of then candidate Donald Trump at a campaign rally in Illinois, a Black woman quietly opened her copy of Citizen and began to read, holding the book at eye level and exposing its cover directly to the television cameras. When reprimanded by an older white man, she refused to put the book down, and the video of their exchange went viral, remediated as an animated GIF.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from The Look of the Book: Jackets, Covers and Art at the Edges of Literature by Peter Mendelsund and David J. Alworth, copyright © 2020. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Previous Article

Do Global Financial Crises Inevitably Reinforce Capitalism?Next Article

The 10 Best Book Coversof November