We Shall Overcome: John Lewis on the Symbolism of the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the Urgency of the Civil Rights Movement

The Late Activist and Congressman in Conversation with C-SPAN's Brian Lamb

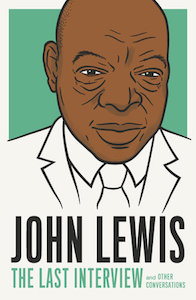

The following excerpt is from John Lewis: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations, published by Melville House books as part of its acclaimed Last Interview series, which compiles iconic interviews done by giants in the world of arts and letters, as well as the final interview they ever gave. In this 2012 interview, Congressman John Lewis spoke with C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb about his involvement in the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

*

BRIAN LAMB: Congressman John Lewis, why did you name your book Across That Bridge?

REP. JOHN LEWIS: Well, during the past few years, I’ve been crossing bridges, rivers, many bridges, bridges of understanding, building bridges, trying to bring people together to create what I like to call the beloved community.

BL: Where does the Edmund Pettus Bridge come into that picture?

JL: Well, the Edmund Pettus Bridge is symbolic of so many bridges, but in 1965, when I was much younger, and head of an organization called the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a group of young people, students, and others attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, to march 50 miles from Selma to Montgomery to dramatize to the nation and to the world that people wanted simply to register to vote. We were walking in twos. And when we arrive at the apex of the bridge down below, we saw a sea of blue, Alabama state troopers. And we continued to walk.

And we came within hearing distance of the state troopers. And a man identified himself and said, “I’m Major John Cloud of the Alabama state troopers. This is an unlawful march. And it will not be allowed to continue.” And one of the young people walking beside me said, “Major, give us a moment to kneel and pray.” And the major said, “Troopers advance.” And they came toward us, beating us with nightsticks and bullwhips, trampling us with horses, and releasing the tear gas.

At the foot of that bridge, I was beaten. I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death. So at the foot of that bridge, I gave a little blood to make it possible for all people to be able to participate in a democratic process. So the book, it just a symbolic bridge of many bridges that we still must cross, rivers that we still must cross, before we build a beloved community, a truly democratic, multiracial society in America.

BL: Did you ever look up who Edmund Pettus was?

JL: I did look up and discover this man, Edmund Pettus, a general in Alabama. You know, the bridge, this particular bridge, was dedicated the same year that I was born, in 1940. So I have a kinship to this bridge. And every year, sometime more than once a year, but every year, I make it a point to go back to that bridge and cross that bridge. And for the past 47 years, I’ve gone back the weekend—the first weekend in March—since 1965.

BL: How did it fit in with everything that was going on back in the 60s?

JL: In order to travel from Montgomery to Selma, you had to cross that bridge. You had to cross the Alabama River. Selma was in the heart of the Black Belt of Alabama. That’s where hundreds and thousands of poor, Black people lived. They had been sharecroppers. They had been tenant farmers.

But this little town, Selma, was a place of commerce. And people would come on a Friday and Saturday to shop. But in Selma, people could not register to vote simply because of the color of their skin. Only 2.1 percent of Blacks were registered to vote. You had to pass a so-called literacy test. On one occasion, a man was asked to count how many bubbles on a bar of soap.

On another occasion, a man was asked to count the number of jelly beans in a jar. People stood in what I call unmovable lines. The only time you could even attempt to go down to the county courthouse and go up a set of steps to a set of double doors and get a copy of the so-called literacy test and the application was on the first and third Mondays of each month. And on occasion, the registrar would put up a sign saying the Office of the Registrar is closed. And people went there day in and day out, standing in line. People were beaten. Some arrested and jailed while they stood there.

BL: Today, the mayor of Selma is the second African American to have that job?

JL: The mayor of Selma is the second African American mayor in that city. The city council is a biracial city council. The police chief is an African American. Selma is a different place today. It is a better place today.

BL: What happened to you after you were beaten? Where’d you go?

JL: On that Sunday afternoon, I was beaten. And 47 years later, I don’t recall how I made it back to the little church that we had left from. But apparently, someone literally carried me back to the church. I felt like I was going to die. I do recall, I thought I saw death. I really thought I was going to die.

But I do remember being back at that church, the little Brown Chapel at AME Church in downtown Selma. The church was full to capacity. More than 2,000 people on the outside, trying to get in to protest what had happened on the bridge. And someone asked me to say something. And I stood up and said, “I don’t understand it. I don’t understand it. How President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam and cannot send troops to Selma, Alabama, to protect people whose only desire is to register to vote.”

At the foot of that bridge, I gave a little blood to make it possible for all people to be able to participate in a democratic process.

And the next thing I knew, along with 16 other people, had been transferred to the local hospital in Selma, the Good Samaritan Hospital that was operated by a group of nuns. And these wonderful sisters, they took care of us. And today, many of those sisters are retired, living in Rochester, New York. And I plan to go there to visit them within the next few days.

BL: Anybody severely wounded, that they didn’t get out of the hospital for a long time?

JL: There were people who stayed for a few days, a few weeks. I got out within two days.

BL: Any of the names that were around you, would they be familiar to us, the people you marched with?

JL: Well, I marched with—later, not on that day but later during the week and the following weeks—with Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. King came to the hospital to visit us the next day. And he said to me, he said, “John, don’t worry. We’ll make it from Selma to Montgomery.” He told me that he had made an appeal for religious leaders to come to Selma. And two days later, more than a thousand priests, rabbis, nuns, and ministers came. And they marched to the same point where we had been beaten two days earlier.

And one young minister went out with a group that following Tuesday evening, to try to get something to eat at a local restaurant. They were attacked by members of the Klan. He was so severely beaten, the next day he died at a local hospital in Selma—in Birmingham, Alabama, rather. He was from Boston, Reverend James Reeb.

BL: So when was it that people could leave Selma, walk across the bridge, and go all the way to Montgomery and not get hassled?

JL: We went into federal court and got an order against Sheriff Jim Clark, who was the sheriff of Selma and Dallas County, and against Governor George Wallace. And a federal judge issued an order saying that we had a right to march. President Lyndon Johnson came and spoke to a joint session of the Congress eight days after Bloody Sunday and condemned the violence in Selma, introduced the Voting Rights Act. And before he concluded that speech, he said, “And we shall overcome.” We call it the “We Shall Overcome” speech. It probably was one of the most meaningful speeches any American president had delivered in modern time on the whole question of civil rights.

__________________________________

Excerpted from John Lewis: The Last Interview, part of the Melville House Last Interview series.