“We don’t want charity. We want jobs!” At the Intersection of the Labor and Disability Rights Movements

Kim Kelly on the Disabled Miners Who Fought for Legal Protection

Employment has long been a central pillar of the disability rights movement, and one of the first groups to make that explicit in a public and militant way was the League of the Physically Handicapped. In 1935, six young disabled New Yorkers who were fed up with the WPA’s informal policy of not hiring people with disabilities decided to take their grievances directly to the city’s Emergency Relief Bureau, and started raising hell. After ERB director Oswald Knauth refused to meet with them, the group staged a sit-in inside the ERB’s office, drawing widespread attention and support for their cause. As occupier Hyman Abramowitz told Knauth, “We don’t want charity. We want jobs!”

After nine days, the occupiers were dragged away and arrested. After the trial, the group named themselves the League of the Physically Handicapped, and continued to hold demonstrations, picket, and recruit more members. After three weeks of protests, the WPA offered jobs to forty League members, but the group refused to be placated by scraps, and continued their campaign. Over the next year, they successfully forced the WPA office to hire more than fifteen hundred disabled New Yorkers. The League then took the fight to Washington to challenge the WPA’s stance on “unemployable” workers itself—and ended up occupying the agency’s federal headquarters. “You have to understand that among our people, they were self-conscious about their physical disabilities,” League member Florence Haskell later recalled. “I think [the protests] not only gave us jobs, but it gave us dignity, and a sense of, ‘We are people too.’ ”

In 1940, Paul Strachan founded the American Federation of the Physically Handicapped. Unlike the LPH, which was centered on people with physical disabilities, the AFPH brought together people across the disability spectrum, including disabled veterans, to push for federal disability policy reform, making it the first cross-disability organization in the U.S.. Instead of focusing on individual efforts at inclusion or rehabilitation, Strachan instead saw disability as a class and labor issue, a framework that would be echoed by the later disability justice activists.

The AFPH sought to forge a path to economic security and equal citizenship, lobbying for greater access to government employment, employment placement assistance, and legislation requiring employers to hire people with disabilities. Strachan also spearheaded initiatives like National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week, which Congress recognized in 1945 and which now exists as National Disability Employment Awareness Month. (In a nice bit of foreshadowing, the President’s Committee on National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week would eventually be led by disability activist Justin W. Dart, Jr., who would go on to play an important role in the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.)

The AFPH also received funding from labor organizations and unions, like the AFL, the CIO, the UMWA, and the International Association of Machinists (IAM); the latter would prove to be an especially stalwart ally to disabled workers. Strachan himself had previously worked as a labor organizer, at the Bureau of War Risk Insurance (the predecessor of the Veterans Administration) during World War I, and as a lobbyist for the AFL. It was only natural that the AFPH found allies within the mainstream labor movement.

As Audra Jennings explains in Out of the Horrors of War: Disability Politics in World War II America, “The AFPH agenda offered a concrete link between traditional union concerns about health and safety and newer goals of expanding the protections offered by the welfare state and helped focus labor’s attention on both union and nonunion disabled people.” AFL representative Lewis G. Hines noted during a 1944 hearing in front of the House Committee on Labor, “A great many of these [disabled] folks are members of our organizations,” and as such deserved labor’s backing—and the government’s support.

Meanwhile, in Cleveland, Henry Williams and a group of other Black World War II veterans were developing rehabilitation programs for their fellow disabled GIs, and organizing “wheel-ins” and “body pickets” in front of the mayor’s office to demand adequate rehabilitation centers and housing for returning injured veterans. Post World War II, Black disabled veterans were often shut out of the job training and rehabilitation programs that were their rightful due under the GI Bill and Public Law 16, thanks to the racist and discriminatory practices upheld by medical doctors, psychiatrists, and government officials.

But Williams and his fellow veterans refused to quietly accept unequal treatment. During the same era, the Blind Veterans Association was busy advocating for its members rights to rehabilitation, employment, and accessibility. Formed in 1945 by a group of young soldiers who were recovering from their injuries together at an army hospital in Connecticut, the organization took an explicitly antiracist stance by welcoming Black and Jewish members, and speaking out against racism and antisemitism during a time when all of the largest veterans’ associations excluded Black veterans or had racially segregated chapters.

These groups recognized that disability spans class, race, and gender, and were determined to ensure no one was left behind in the struggle. “Though broken in body, I was fighting with those millions to stamp out those same principles that we fought against during the war,” Williams later reflected, on his time battling discrimination on multiple fronts. “I was fighting for the civil rights of every disabled citizen.”

As the 1970s dawned, another generation of American troops was being sent off to suffer, sicken, and die in yet another bloody war, this time in Vietnam; more than twenty-five thousand young men registered as conscientious objectors to avoid taking part in the slaughter, and some of them joined the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) as an alternative. Founded as part of President Johnson’s War on Poverty campaign and envisioned as a civilian answer to the Peace Corps, VISTA had volunteers spread out all over the country to help bring education and resources to neglected, poverty-stricken communities.

Some of those volunteers headed to Appalachia, where they became enmeshed in local struggles and provided support for pivotal grassroots organizing, especially in West Virginia. There was trouble brewing in the coalfields of Boone County, where miners had spent centuries fighting for decent wages and health-care benefits but were now seeing the results of those hard-fought battles evaporate before their eyes.

At that point, “coal workers’ pneumoconiosis,” an irreversible respiratory disease better known as black lung, had been quietly ravaging generations of miners. Despite coal bosses’ insistence that the dust was actually beneficial, or at least not actively harmful, by 1968 a Public Health Survey had found that one in ten working miners and one in five retirees had a coal dust-related lung ailment, making up one hundred thousand people who had been left partially or fully disabled by their dirty, hazardous working conditions.

As modern medicine finally caught up and properly identified their ailment as an occupational disease, miners and their families began pushing for justice. That year, a coalition of disabled coal miners, local union leaders, and other mine workers founded the West Virginia Black Lung Association, but by then, a man named Robert Payne had already gotten the ball rolling.

Robert Payne started working in the West Virginia coal mines as a child of fifteen and joined the UMWA as soon as he was able. As he once said, “I was born a union man because my daddy was a union man,” and Payne would more than live up to that legacy. Before he became an activist, though, he was a coal miner, one who was repeatedly injured on the job. First he lost several fingers, and then he lost his ability to work after being severely burned in a mine explosion.

It was bad timing on his part, though of course it wasn’t his fault; the corrupt mismanagement of UMWA president Tony Boyle had tanked the UMWA-controlled Welfare and Retirement Fund, which previous UMWA president John L. Lewis had implemented in the 1950s to provide for workers who had given their bodies (and often, their lives) to the mines. As a result, by 1964, nearly 20 percent of the fund’s beneficiaries—disabled miners and their widowed spouses—had lost their benefits, and Robert Payne was far from being alone in his determination to make things right.

As modern medicine finally caught up and properly identified their ailment as an occupational disease, miners and their families began pushing for justice.

In 1967, he and other miners who’d been shafted formed the Disabled Miners and Widows of Southern West Virginia, and petitioned UMWA leadership to have their benefits restored. When they received no response, Payne drew upon his experience as an evangelical preacher and started calling upon his people to mobilize. They led a series of rallies and wildcat strikes (i.e., work stoppages and walkouts that are not sanctioned by union leadership) across West Virginia to draw attention to the desperate conditions coal miners continued to face.

Even after mine operators took out restraining orders against them and got the police involved, the Disabled Miners held firm. Payne and three others were eventually jailed for their trouble and charged with contempt of court. Meanwhile, UMWA President Boyle refused to meet with them. The Disabled Miners ended up suing the union, and as a result of their litigation, $11.5 million was paid out to disabled miners and miners’ widows, and those who’d lost benefits saw them reinstated. The miners had won this first round, but a larger battle was already brewing.

On November 20, 1968, disaster struck, and brought the miners’ plight out from underground and into the national spotlight. On that day, a massive explosion consumed the Consol No. 9 coal mine outside of Farmington, West Virginia; 78 miners lost their lives, and the bodies of 9 of the victims were never recovered. That year alone, 311 coal miners died in work-related accidents. “Today is four months since the terrible tragedy and 78 men are still entombed—our husbands, fathers, and sons,” Sara Lee Kaznoski, whose husband was killed in the explosion, told a roomful of senators during a congressional hearing on mine safety following the disaster. “You must all see that the laws are strengthened for the future of coal miners. It’s up to each and every one of you.”

As families mourned and politicians pontificated about safety regulations, rank-and-file miners were busy battling an old foe with a newfound sense of urgency. Mine operators were still doing little or nothing to control coal dust inside their mines (or were actively working to flout safety regulations), and the Black Lung Association began organizing around a new state legislature bill they hoped would force companies to meaningfully tackle the coal dust problem and provide compensation to black lung victims. They brought three thousand miners to Charleston in January to hear the first draft of a potential black lung bill, but by February 18, 1969, it had become clear that more persuasion was needed, and the miners began to walk out on their jobs.

Beginning at Westmoreland Coal’s East Gulf Mine, the wildcat strike spread like wildfire throughout the state, jumping from mine to mine as one by one the workers downed their tools. By the following week, forty thousand coal miners had shut down virtually all the coal mines in West Virginia in the largest political strike in U.S. history. On February 27, the streets of the state’s capital, Charleston, filled with one thousand miners and their families as they marched to the statehouse to urge legislators to pass legislation addressing their concerns. Led by organizers from the Black Lung Association, they chanted “No law, no work!” as they marched; as the Charleston Gazette reported, one young boy, Mark Legg, carried a sign reading, “My daddy is a coal miner. He need’s protection.”

Finally, on March 12, Governor Arch Moore signed a bill into law that set strict safety standards on coal dust levels inside the mines and provided compensation for black lung victims and their widowed spouses. It was the first legislation in the country to recognize black lung as a compensable occupational disease, but it would not be the last, and the black lung crisis would continue to claim new generations of miners to come.

However, the miners’ success and the increased visibility their strike had brought to the black lung crisis made a marked impact, and their tireless work advocating for improved safety regulations undoubtedly saved countless lives. (In their free time, the BLA would later become involved in the Miners for Democracy movement, which challenged internal corruption in the UMWA and eventually sent Tony Boyle packing).

Their actions spurred the passage of a series of important federal mine safety laws, including the 1969 Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act, its expansion with the Black Lung Benefits Act in 1972 (which Nixon only grudgingly signed), and the 1977 Federal Mine Safety and Health Act, which strengthened and expanded miners’ rights, required mine rescue teams to be established, and created the Mine Safety and Health Administration. “The strike’s the onliest weapon the rank and file has. . . . There wasn’t no one person responsible for what happened in 1969,” Robert Payne, the founder of the Disabled Miners and Widows of Southern West Virginia, reflected in a 1972 interview. “Everybody was responsible for it. It was all the miners and disabled miners striking to get this Black Lung law passed.”

_______________________________________________________________

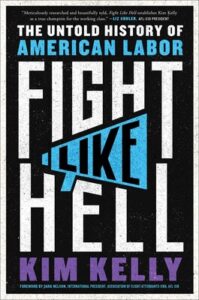

Copyright © 2022 by Kim Kelly. From Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor by Kim Kelly. Reprinted by permission of Atria/One Signal Publishers, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Kim Kelly

Kim Kelly is an independent journalist, author, and organizer. She has been a regular labor columnist for Teen Vogue since 2018, and her writing on labor, class, politics, and culture has appeared in The New Republic, The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Baffler, The Nation, the Columbia Journalism Review, and Esquire, among many others. Kelly has also worked as a video correspondent for More Perfect Union, The Real News Network, and Means TV. Previously, she was the heavy metal editor at “Noisey,” VICE’s music vertical, and was an original member of the VICE Union. A third-generation union member, she is a member of the Industrial Workers of the World’s Freelance Journalists Union as well as a member and elected councilperson for the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE). She was born in the heart of the South Jersey Pine Barrens, and currently lives in Philadelphia with a hard-workin’ man, a couple of taxidermied bears, and way too many books.