Waves and Wipeouts: On Learning How to Surf As an Adult

David Litt Considers the Value of Fear and Persistence in the Pursuit of a New Skill

The motto of OCEARCH, a leading shark research organization, is “Facts Over Fear.” It’s a bad motto. If there’s anything we’ve learned from recent history, it’s that facts and fear are not mutually exclusive.

I demonstrated this myself when, a week before my second surf lesson, I logged on to the OCEARCH website and learned there was an 880-pound great white shark lurking off the New Jersey coast. Her name was Freya. Fifteen months earlier, a researcher had clipped a homing beacon to her fin the way you might slip a Bluetooth tracker into your luggage, adding her to a roster of several hundred tagged sharks cruising the world’s oceans. Occasionally, a shark’s beacon emits a ping, and scientists study these pings to learn more about shark movement. This is an indirect way of saying there’s still an awful lot scientists don’t know about sharks, including, in most cases, where they are.

Sharks are noble creatures. Reams of data show they rarely pose a threat to humans, and as apex predators, they’re essential to healthy ocean ecosystems. Demonizing sharks is barbaric. Worrying about them is anti-science. As someone who cares about the planet, I believed these things wholeheartedly.

While flailing in pursuit of whitewater may not have been fun, it was something different to think about. It paused the spin cycle in my mind.

As someone who prefers his internal organs to remain on the inside, however, I found it harder to toe the party line. The odds of being bitten by a shark are almost zero. But for a few unlucky people, the crucial part of that sentence is “almost.” In much the way my grandfather once ate several salmon-flavored dog biscuits thinking they were gourmet crackers, sharks occasionally—but very memorably—confuse people for seals. Surfers, with seal-shaped boards and dark wetsuits, are particularly susceptible to such mix-ups. The risk is especially great if a surfer thrashes against the water in the manner of a wounded seal.

I was new to paddling. All I did was thrash.

For a little while, Freya stayed put. Then, as though she, too, had booked a lesson with my surf instructor Katie, she began cruising up the coast. By the time I removed my Wavestorm from the car in Bradley Beach, two towns south of Asbury, Freya’s most recent ping had come from an undersea canyon directly offshore.

“Everything okay?” asked Katie as we waded in. The waves were tiny, but I took careful steps, pushing my foamie ahead of me as a shield.

“All good,” I replied. Then, trying to sound casual, I added, “Oh, by the way, did you know there’s a great white shark in the area?”

“Yeah, Barry!”

The idea that Freya had a colleague—and that this second shark was not a fair-minded Nordic lady but a ruggedly individualistic American male—was a fact for which I was unprepared.

“If I see a shark,” I asked, “or sharks, plural, what should I, you know, do?”

Katie cocked her head, as if the question had never before occurred to her.

“I wouldn’t worry about it.”

That’s nice, I thought, but why wouldn’t you worry about it? Isn’t worrying about sharks while standing in shark-infested waters exactly what a person should do? I’d hoped to recapture my Woochee moment, but the ocean was alive with phantom fins and toothy shadows, and I was far too busy keeping watch to catch a wave. Even when exhaustion dulled my vigilance, my worries didn’t disappear. They just moved on to something else.

“I’ve noticed a problem,” I said to Katie just before our lesson ended. “It frequently feels like the wave is going to break on top of me, and, well, snap me in half. What do I do about that?”

I braced myself for another unhelpful don’t-worry-about-it response. To my surprise, Katie beamed.

“The flower of fear!”

“Huh?”

She leaned over my board, catching my gaze the way my grandfather, when he wasn’t eating dog biscuits, used to look at me before sharing a profound and hard-earned truth.

“When you paddle for a wave, and you feel the flower of fear opening, it’s a good thing. That feeling is one of the most important parts of surfing. It’s how you know you’re in the right spot.”

This was a notion I’d never encountered. I’d always thought of fear as something to be overcome or succumbed to, faced or ignored. But the way Katie saw it, fear, when harnessed correctly, was not just good but essential, a source of power and drive. In four simple words, she had described not just a different way to think about waves, but a different way to think about everything. I floated on my Wavestorm, doing my best to embrace this transformational new idea.

“Or,” I said, unable to help myself, “the flower of fear means you’re about to die.”

Pointing my board toward the lifeguard tower, I waited for the “whitewater,” the churning foam that erupts from a breaking wave and surges to shore. As it neared, I psyched myself up with a mantra.

To the beach!

This proved aspirational rather than descriptive. By the time I planted my right foot, my Wavestorm and I were already moving in opposite directions, and I flew backward like a cartoon drunk slipping on a banana peel. After a brief dunking, I scrambled to my feet in the knee-deep water and gathered my board. As I stood there, catching my breath and marinating in my own ineptitude, an entire bachelorette party glided happily and competently toward shore.

An increment of surfing, like one of therapy, is known as a session. As in, “Epic session, bro!” or “You down for an afternoon session?” or “Shredding whatever paltry scraps of hope I’d brought with me to the dog beach, my inaugural solo surf session went from bad to worse.” I wiped out approximately twenty times. My toes were pinched by crabs approximately thirty times. I got to my feet twice, and even those two rides were nothing like the one I’d experienced with Katie that first morning. They felt less like flying on a magic carpet than standing on a rusty conveyer belt. When I got home, every muscle twitched from exhaustion and overuse.

“Did you have fun?” asked my wife Jacqui hopefully.

“Fun? Definitely not.”

Part of the problem was my age. The best time to start surfing, I learned long after the knowledge might have helped me, is between five and seven years old. Fifteen is pushing it. Twenty is over the hill. Thirty is geriatric. To pick up a board at thirty-five, as I did, is the rough equivalent of signing up for guitar lessons on your deathbed.

You might think the hopelessness of the task would deter people from trying, but so far that hasn’t been the case. I was one of millions of adults who grabbed a foamboard during the pandemic. The surf industry, which happily sells shorts and T-shirts to customers regardless of skill level, has welcomed the influx of beginners. So has the internet, where a pantheon of viral gurus caters to those picking up a board later in life.

Hardcore surfers have taken a slightly different approach to the newcomers. They hate them. Some use “VAL”—short for “vulnerable adult learner”—as a slur. Others direct their anger at the beginners’ equipment. In surf-speak, “Dude, lots of foamies in the water” roughly translates to “There are novices here, and they are subhuman, and their mere presence fills me with loathing and rage.”

A few surfers are more eloquent, but no less disdainful. At Glide, the surf shop where Katie worked, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life sat on a table between the sunscreen and wax. I bought a copy. One hundred twenty-three pages in, I read author William Finnegan—who by all accounts is an otherwise liberal and tolerant person—describe adult learners like me.

“People who tried to start at an advanced age, meaning over fourteen, had, in my experience, almost no chance of becoming proficient, and usually suffered pain and sorrow before they quit.”

I remained skeptical that fear was a flower. But I certainly preferred it to the cactus of existential dread.

How dare he assume something like that? I thought. Also, how dare he be right? While my own surfing life spanned all of two weeks, I’d already compiled an encyclopedia of discomfort: the swollen knee from landing funny on the deck; the throbbing in my shoulders each time I thrashed out another paddle stroke; the bruised left butt cheek from falling backward in ankle-deep water.

Other setbacks, while less painful, were no less sorrowful. One morning at the dog beach, a wipeout tossed me over my heelside rail and deposited me a few yards from shore. Sighing with frustration, I got to my feet, and had just reeled in my leash when a knee-high wave plucked my Wavestorm from my hands and flung it into another rider’s path. He catapulted over the nose of his board, splatted bellydown into the shallow surf, and emerged from the water dripping and ferocious, a beefy, balding sea monster.

“Fucking kook!” he said.

This, I knew, was a surf-specific putdown, one whose meaning sat at the pungent four-way intersection of moron, newbie, dork, and asshole. He stomped toward me.

“Fucking kook,” he muttered again.

Living, as I do, in a nation choking on rage and firearms, the sensible reaction would have been to mumble an apology. But I didn’t appreciate being insulted, and I could feel my blood boil.

“Hey,” I snapped, “I have no idea what I’m doing!”

It took us both a second to realize I’d taken his side. Anger waylaid by confusion, the sea monster hopped back on his board (he was quite graceful, given his proportions and temperament) and paddled away. But my own words hung in the air, far more devastating than his insult. Even by the low standards of adult learners on foamies, I was terrible at this. I myself had said so. And I seemed destined to remain terrible forever.

Yet I didn’t quit. I returned to the dog beach twice more the week of my first solo session, and four more times the week after that. I could count my total number of successful pop-ups on my fingers, so it wasn’t the rush of riding waves that kept me coming back. It was something deeper. During each surf session I felt frustrated, exhausted, humiliated, terrified, depleted, confused, and sore—but never depressed. While flailing in pursuit of whitewater may not have been fun, it was something different to think about. It paused the spin cycle in my mind.

Surfing even made it easier to stop worrying about the news. At one time, I’d wanted to help save the world. Now I wanted to forget it needed saving, and my new hobby made that possible. Instead of asking, Are we witnessing, in real time, the devastation of our planet, the rise of fascism, and the death of the American Dream? I asked, Is this wave about to shatter my spine? I remained skeptical that fear was a flower. But I certainly preferred it to the cactus of existential dread.

__________________________________

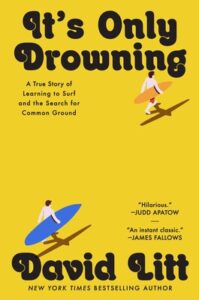

Excerpted from It’s Only Drowning: A True Story of Learning to Surf and the Search for Common Ground by David Litt. Copyright © 2025 by David Litt. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

David Litt

David Litt is the New York Times bestselling author of Thanks, Obama; Democracy in One Book or Less; and It’s Only Drowning. A former senior speechwriter for Barack Obama, described as “the comic muse for the president” for his work on White House Correspondents’ Dinner monologues, he has also written for The New York Times, The Atlantic, ,The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Cosmopolitan, and more. Along with writing speeches and jokes for political figures, athletes, Fortune 500 CEOs, and philanthropists, David was the head writer/producer at Funny Or Die, DC, and has written and sold comedy pilots for Comedy Central, ABC, and NBC. He and his wife divide their time between Washington, DC, and Asbury Park, New Jersey.