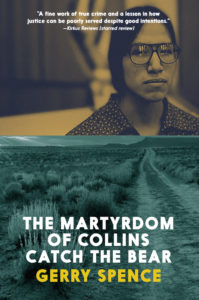

Was a Lakota Sioux Wrongly Accused of Murder During the Wounded Knee Occupation?

Gerry Spence on the Case of Collins Catch the Bear Frustrated

I’d written something like a hundred pages on an old electric typewriter—my writer’s weapon in those days—about my defense of Collins Catch the Bear, a Lakota Sioux who’d been charged with the murder of a white man. Then Catch the Bear, without offering reason or explanation, which was his way, ordered that I stop writing. So, I tossed my work onto the top shelf of a closet, and the pages yellowed and curled in protest for nearly 30 years.

In the decades that hurtled by, I lost contact with Catch the Bear. I remembered him as a bright, articulate young man who’d become dedicated to the cause of Indian rights, trying his lawyers’ patience with a host of problems, which I recount in the pages that follow. Then: silence. I supposed he was either in prison or rotting away on the reservation in South Dakota.

Then, a short time ago, fate intervened, and I found myself freed to tell his story. America’s attention to Indian rights, as capricious as it has been, was recently revived when representatives of 280 tribes from across the nation joined to peaceably protest the Dakota Access Pipeline’s invasion of sacred Indian lands in North Dakota. Indian demonstrations, both peaceful and deadly, were nothing new in the Dakotas.

Collins Catch the Bear offered no remarkable history except multiple convictions for various crimes, and when I asked him about his life, he was often unresponsive or his answers vague.In 1973 the American Indian Movement (AIM), championed by Russell Means, the infamous Indian renegade, occupied the Indian village of Wounded Knee, in South Dakota, in a hostile 71-day siege in which two Indians lost their lives and a federal officer was shot and paralyzed. In 1982, the Lakota Sioux established the Yellow under Camp, just outside Rapid City, South Dakota. This unauthorized encroachment on the National Forest was the progeny of the same Russell Means of the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation.

Both whites and Indians had their say regarding the camp, and the killing continued: on July 21st, Clarence Tollefson, a 49-year-old white man from Rapid City was fatally shot at the camp. Such deadly confrontations seemed sealed in the genes of history.

According to the verbiage of Rodney Lefholz, then the state’s prosecutor, who’d recently announced his candidacy for South Dakota attorney general, it was one Collins Catch the Bear who had shot and killed Tollefson, and justice demanded that he be forthwith charged, tried, convicted, and thereafter permanently eliminated from the population. In those days (and perhaps today in some quarters of the state), Indians were viewed with approximately the same affection as coyotes, rats, and other vermin.

I’d been coaxed into the case by Jim Leach, of Rapid City, a kid who’d been out of law school a few years but not long enough to shed his romantic notions, like Don Quixote in his chivalric search for justice. Leach was irrevocably wedded to the case. Why, I didn’t know. But one thing I’d learned (the hard way) was that embracing virtue often leads to unforeseen misadventures. Catch the Bear’s trial was imminent, and Leach said he needed my help defending him.

Before I take on any case, I try to discover who the client is. I want to know something about the seed and roots as well as the blossom. Collins Catch the Bear offered no remarkable history except multiple convictions for various crimes, and when I asked him about his life, he was often unresponsive or his answers vague. Moreover, he was unable to pay the first penny for his defense, covering not even the barest of expenses.

I’ve long contended that lawyers ought not commit to a case unless they’ve been able to discover, after a charitable search, something in the client they can care about at the heart level. I’ve represented alleged killers and thieves and crooks of many stripes, and I’ve found that if one cuts through the hard, often hostile survival armor of even the most depraved, one will often find a tortured soul: a child wounded by parents hopelessly lost to drugs and alcohol or, too often, stifled by utter poverty—but under it all, a human being worth caring about.

In my research, I tried to stay in tune with the requiem that seemed to accompany Catch the Bear’s life.For Catch the Bear’s part, he often came off like a cipher in glasses. Perhaps, I thought, the tribal records would furnish more insights than the man seemed capable of providing. So, it was there that Leach and I started our archeological dig in search of Collins Catch the Bear. And, indeed, what we found was a young, lost Sioux in search of the same elusive person: himself.

To bring me up to speed on the case, Jim Leach provided me with boxes of forgotten records, some incomplete, the events they related inviting careful reconstruction.

Some lapses in the records were filled by the recollections of people who were there and by suppositions based on our own best judgment. In my research, I tried to stay in tune with the requiem that seemed to accompany Catch the Bear’s life. As a lawyer, I was, from time to time, required to create characters and conversations to illustrate the carryings on of persons who were symbolic of the events and times. And always, I relied on Jim’s knowledge of the case, his earlier notes, and the sometimes reluctant and often truncated memory of Collins Catch the Bear himself.

As my research progressed, what emerged was a chronicle of hurt and degradation. Later, long after the case and Collins’s death, I knew I was asking readers to accompany me on a painful trek while writing this book. Why should they join me? To put it in another way, why should I, or they, care?

There’s something about being human that invites our concern for those who have drawn the short straw in life. Many of the people on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation faced a challenge for survival. This is the story of one of them: Collins Catch the Bear. Derelict or saint? We shall see. It is also the story of trial lawyers who found themselves committed to the defense of a Lakota Sioux charged with the murder of a white man. After the passage of these fleeting years, the cellular question remains: Did we fail?

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Martyrdom of Collins Catch the Bear. Used with the permission of the publisher, Seven Stories Press. Copyright © 2020 by Gerry Spence.