Vivian Gornick on the Magnetism of Edna St. Vincent Millay

Looking Back at the "Wild and Elusive" Poet

In 1970 Nancy Milford published a famous biography of Zelda Fitzgerald, one of the fabled bad girls of American literary bohemia. The book is remarkable for the power with which it brings to life the romantic disorder that plagued the Fitzgeralds—how loved they were for it!—and also for revealing how much more trapped in it was Zelda than Scott. While he could make literature out of their shared circumstance she, his raw material, could only be consumed by it. She had been adored for the chaos within: it was her gift and her karma. There was nothing for it but to go on being outrageous to the truly bitter end.

At the very same time that Zelda was riding the crest of her extraordinary wave, another famous bad girl of American arts was riding hers. This one, however, is known to us not as the companion to the talent but the talent itself. Madly bohemian, Edna St. Vincent Millay, in her glory years, was as well known for her capacity to arouse the national fantasy about free love and reckless living as for her poetry. She was, as Nancy Milford tells us, “the first American figure to rival the personal adulation of Byron.” Millay, in fact, drew the same kind of crowds that Byron drew: “Her performing self made people feel they had seen the muse alive and just within reach . . . [S]he not only brought them to their feet, she brought them to her. In the heart of the Depression her collection of sonnets Fatal Interview sold 35,000 copies within the first two weeks of its publication.” This wasn’t because America had become a nation of poetry lovers.

Edna Millay was born in 1892 and grew up, in hardship and in beauty, on the coast of Maine. She was one of three daughters born to a poor, independent-minded mother (a wig-maker and visiting nurse) who, in 1900, told an incapable husband to get out, and set about raising her daughters alone. Cora Millay was an original: tough, smart, literate. Inside her rough edges a romantic was burning with odd ambition for her girls if not for herself: “I had a chip on my shoulder for them. It is a vicarious thing to live on the edge of everything, but with the parent against the world it is stronger yet . . . [T]hey always had a line out to the beautiful and the tragic . . . I let the girls realize their poverty: I let them realize what every advantage cost me in the effort to live.”

They adored her inordinately—in her company, the ardor not for life but of life became a formative experience—and within the psyche of each girl this adoration for the mother wove itself into an unusual family romance. In the ’20s, in Greenwich Village, people watched Cora Millay and her three daughters rambling about together, raptly involved with one another, a little band of countrywomen hitting the big city, looking like some eerie version of Little Women. Inside the originality and high spirits something secret, mocking, untouchable: they were for one another as they would be for no one else; a prefiguration of all the loneliness to come.

Of course, at the beating-heart center was Edna—always Edna. They were there because of Edna; because Edna had written a famous poem (“Renascence”) at twenty, received the support of a rich patron, gone to Vassar and then, in the spring of 1917, come to New York to begin her amazing career of poetry and seduction. As Malcolm Cowley remembered it, “They were each lovely girls. But Edna . . . [s]he’d break your heart. There was something wild and elusive about her.”

In the poems she would often, with spice and daring, pronounce those she seduced ennobled because they had been loved and left by her.

She’d been that at twelve, she’d be that at forty: wild and elusive. Or, rather, intent on making people experience her as wild and elusive. This was the thing, always, at the heart of her character and of her work: her bold need for self-dramatization. Edmund Wilson put it best, and for countless others, when he described meeting her—again in the Village, in the ’20s—at a party where she was reading her poems. Her voice, he said, was absolutely thrilling. It gave her the “power of imposing herself on others through a medium that unburdened the emotions of solitude. The company hushed and listened as people do to music—her authority was always complete . . . She was one of those women whose features are not perfect and who in their moments of dimness may not seem even pretty, but who, excited by the blood or the spirit, become almost supernaturally beautiful.”

Dorothy Thompson—who knew Millay in Budapest, at the height of her fame, on a trip to Europe—put it another way: “She was a little bitch, a genius, a cross between a gamin and an angel . . . She sat before the glass and combed her lovely hair, over and over. Narcissan. She really never loved anyone except herself . . . I had to go back to Vienna and left her the toast of half the town. Handed her all I had because she was an angel . . . She might have left Josef [Thompson’s husband] alone, but not that, either.”

It had nothing to do with sensuality, everything to do with the romantic exercise of will: a will bent on inducing lifelong yearning in those around her. The magnetism lay in a triumph of attitude that had been hers since girlhood. She saw herself as linked to a higher destiny. In the poems she would often, with spice and daring, pronounce those she seduced ennobled because they had been loved and left by her. They should all, she felt, be proud to have served the higher cause—the sheer intensity—of her self-devotion.

Nothing and no one mattered except the intensity. How to keep it alive became the central question of her life. The answer, of course, was always the same: to drink, sleep around, and make art—nonstop. Before she was through, there’d been a thousand men in her bed, a few thousand drinks under her belt, and more money made from the writing of poetry than any other American poet had seen before or, perhaps, since. The fame came because her need to be herself at all costs meshed perfectly with the need of the time. In a profile of her in the New Yorker in 1925, the writer explains why hers is the voice of the moment: “[T]he poems celebrate the loves of [the] footloose . . . The only genuine surrender is to death . . . It is the only intensity available after a love that has burned on nothing but itself”; the writer goes on to observe that the generation that had just gone to war “had seen nothing so accurate about itself in print.”

This poet, once so beloved, is entirely unknown today. We do not read her work or, if we do, we experience very little of what was experienced during her lifetime. If you ask why this is so, the answer will probably be, “They’re sentimental.” By which is meant, not that Millay’s formality or subject matter or attitudes are out of fashion but, rather, that the poems simply do not go deep enough. The material is not sufficiently transformed. If it was, it will be said, none of the rest would matter. The poems would then be news that stayed news.

These women were possessed of a blazing, raging, murderous extremity: brilliant, driven, unforgiving.

Yet, as a figure, Edna Millay compels. Something in her life signifies. It occurred to me, reading Milford’s biography, that she was, not the Byron of her day but, more accurately, the Anne Sexton of her day. Another amazing seducer-through-poetry whose public readings drove people wild but whose work now—alone on the page, thirty years later, without the special pleading of a live performance—has much less impact than it did when the collective reader could feel, behind the words, the stirring presence of the actor-poet. In the flesh, these two literary vamps both generated a powerful allure—to which they themselves became addicted—that spread the reputation of the poems far and wide. As a result, they hungered to remain vamps forever and, in fact, never progressed, either of them, in the life or in the work, beyond this urgency. In each case the vamping can now be seen as a harbinger of some internal nihilism, something determined to eat itself alive that seems emblematic of the time— and it is this that holds our attention.

These women were possessed of a blazing, raging, murderous extremity: brilliant, driven, unforgiving. Compelled to consume all that came its way, inevitably it consumed itself. Sylvia Plath might be added to their number—certainly she died for the rage not the poetry—and, of course, there was Zelda Fitzgerald. The disparities in literary talent among them notwithstanding, they are all vivid examples of a kind of willed temperamental outrage at having been born into ordinary human damage. They be damned if they’d submit—and they were.

Trapped in the lives of these rather fabulous creatures is a piece of glory and sorrow on the grand scale. The social and sexual anarchy to which both Millay and Fitzgerald were seriously devoted is of a kind that no experience can influence. Hard, mean, and immutable, it inflicts an intolerable loneliness, and indeed, the loneliness cannot be tolerated. Sexton and Plath killed themselves and Zelda Fitzgerald went mad; Millay, on the other hand, perhaps the most complicated of the lot, devised an ending for herself altogether more interesting. In the last part of her life, she lived alone, with her revering husband, in a rural retreat called Steepletop. Here, a lovely estate three hours from New York City was created solely to serve Edna’s art. But as time went on, and the power of her youthful beauty evaporated, it was her melancholy not her art that was served. She retreated steadily into booze and drugs. Her husband, insistent upon the genius in his keeping, continued to keep the house in perpetual readiness for Edna’s muse. As they waited, the place grew shabbier and shabbier. She fell into morphine addiction, so did he, less and less did they leave home, and at last they were both buried alive in what had become an eerie fantasy of the life they were waiting to live. In short: Steepletop became Sunset Boulevard.

__________________________________

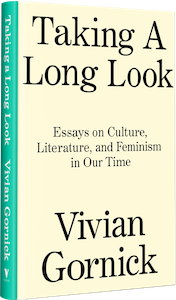

Excerpted from Taking a Look: Essays on Culture, Literature, and Feminism in Our Time. Used with the permission of the publisher, Verso Books. Copyright © 2021 by Vivian Gornick.

Vivian Gornick

Vivian Gornick is the bestselling author of Unfinished Business along with the acclaimed memoirs Fierce Attachments and The Odd Woman and the City, a biography of Emma Goldman, and three essay collections: The Men in My Life, Approaching Eye Level, and The End of the Novel of Love, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.