“The first song is about rescuing,” said Stephen Haff, “and now we’re brainstorming what we want to rescue.”

On a cold Monday night in January, we were at Still Waters in a Storm, the “one-room schoolhouse” learning sanctuary for immigrant children opened by Stephen ten years ago in this former storefront on Stanhope Street in Bushwick, Brooklyn—Stephen is Still Waters’ director and only fulltime teacher. He was telling me about their new Don Quixote Project, which he sees as lasting five years. Over those years Still Waters kids, Stephen told me, are going to slowly read and study Don Quixote and work together on retelling Cervantes’ classic in various ways, through song, and theater. The goal for this first song, the “Rescuing Song,” was for the children to perform it in public for the first time on April 19, at the Still Waters benefit at Symphony Space in New York, where they’d be accompanied by the likes of Rosanne Cash, Steve Earle and Wesley Stace, who’d also play their own music. They had three months to write it and get it ready.

But that Monday, January 29, before getting down to work, the children clearly wanted to talk about something else. That weekend protestors had massed at JFK airport in response to Trump’s Muslim ban. And Mexico’s president had just cancelled a planned visit to Washington because of Trump’s belligerent “wall” rhetoric, among other contentious issues. Trump was on the children’s mind.

“My social studies teacher told me that the Muslims need to get back because they live here but Trump wants them to stay there,” said one of the children. Stephen decided to spend some time discussing the Trump administration’s threats to punish New York for being a sanctuary city by taking away funds. Why did they think Trump wanted to do that? “Because we are the symbol for freedom,” said 13-year-old Jonathan, who always has a thick lock of hair falling over his left eye, “like America isn’t but New York City is.” Nine-year-old Bryan said, “Donald Trump should visit the Statue of Liberty and see the broken chain at her feet. That broken chain means freedom.” And eight-year-old Keyla, with two thick braids and large blazing eyes, spoke emphatically: “Donald Trump has a small and dark heart.”

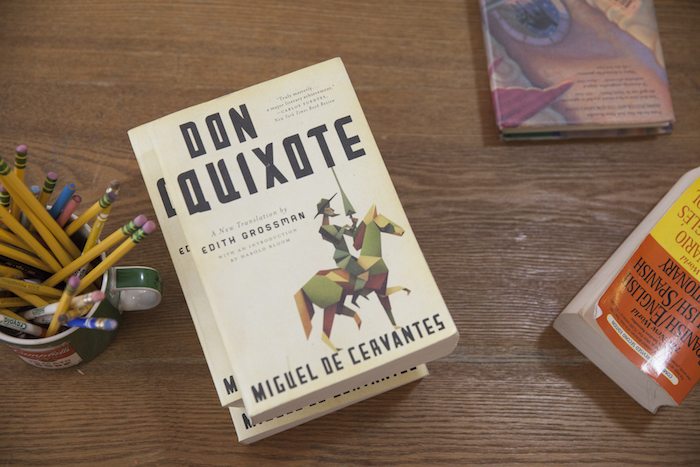

Throughout that autumn, the students had been reading Don Quixote both in the original Spanish and in Edith Grossman’s celebrated English translation. So far, they’d gotten up to chapter eight. Monday and Tuesday evenings are dedicated to the project, when a core group of approximately 15 students, ages 7 to 15, meets to discuss what they’ve read and to collaboratively translate certain passages into their own words. Over the next five years these children will move from childhood into adolescence alongside Cervantes’s text. The idea, Stephen explained, is for Don Quixote to become a source of collective identity for the children, who mostly live in Bushwick, and are almost all from Mexican and Ecuadoran immigrant families. He wants them to weave stories from their own lives into what they adapt from Cervantes’s novel for their theater and song versions, and for those songs, he said, “to be inspired by moments or ideas that the kids feel are part of their own lives.” Eventually a Still Waters theater troupe will perform these songs in serial “Adventure Plays” fashioned from the same material.

Edith Grossman had recently visited Still Waters to talk to the children about Don Quixote—afterward she declared that the novel “has never been in better hands”—and so had William Egginton, a Johns Hopkins professor and author of a recent book about Cervantes, The Man Who Invented Fiction. Other recent guests include Mexican novelist Alvaro Enrigue, and on the non-literary side of things, an expert in wind turbines had visited to teach the children about the physics of windmills.

![]()

Stephen Haff, 52, who with his messy blond-gray hair, intense blue eyes and expressive lips recalls a rumpled, gentler Klaus Kinski, with eyeglasses riding low on his nose, usually wearing a Mets cap, was born in Colorado and raised in Canada. He studied literature as an undergraduate, and came to the US to earn a master’s degree at the Yale School of Drama, after which he worked in New York theater before discovering his calling, or at least made the first life-changing decisions that brought him to that calling: he became a high school teacher in the Bronx and then in Bushwick, where he also formed a theater group for inner-city kids, the Real People Theater, that was invited to perform Shakespeare in Europe and Canada and elsewhere. That project, but also his frustration with the seemingly intractable, harsh realities of New York’s public school system—he left his teaching job in 2008—and the overcoming of his own personal crisis with depression and bipolar disorder along the way, resulted in Stephen’s founding of Still Waters in a Storm as an experimental collaborative learning space.

Kimberly (green shirt) and Emanie kick a ball out front before play practice. All photos Rachel Cobb.

Kimberly (green shirt) and Emanie kick a ball out front before play practice. All photos Rachel Cobb.

For the first two years, he met with former high school students and members of the theater group in a pizza parlor; successful colleagues from his past in professional theater helped finance the move to Stanhope Street. Stephen, his wife, and their three children live in Bushwick, too; along with his family, Still Waters in a Storm is the center of his life, a visionary laboratory of educational and artistic creativity and service to community. Stephen told me that the Don Quixote Project represents the culmination of all that he’s learned from over 20 years of involvement in theater and as an activist educator.

That first song, about rescuing, was inspired by a pair of incidents in chapters four and five of Don Quixote, when the book’s questing hero, the Sorrowful Knight, the righter of wrongs, first tries to free a shepherd boy from a whipping by his master, and by a subsequent scene in which a farmer comes upon Don Quixote lying on the ground after he has been badly pummeled by a muleteer. The farmer, in Grossman’s translation, “wiped the fallen man’s face, which was covered in dust, and lifted him onto his own donkey.” To the kids at Still Waters, that moment of kindness to a needy stranger became a foundation stone to the building of their first Don Quixote song, one inspired by the challenge and meaning of rescue right now. And it was a response to the insecurities and fears that Donald Trump’s three-week-old presidency was bringing into the lives of immigrant families in Bushwick and throughout this country.

Eight-year-old Keyla, with two thick braids and large blazing eyes, spoke emphatically: “Donald Trump has a small and dark heart.”

“Imagine how they are feeling,” Stephen replied when I asked how Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies were affecting the kids at Still Waters. “They talk about it every day in conversation outside of class, sometimes with fear and tension, other times by laughing, and they write about it, and they relate what we’re studying—Quixote, ancient Roman political leaders—to what’s happening today in this country.”

![]()

At first I’d planned to visit Still Waters, riding the G and L trains to the DeKalb Avenue stop, for two or three Mondays, thinking that would be enough to satisfy my curiosity about the Quixote Project. But Stephen Haff never lets go of a friend, or potential friend, of Still Waters so easily, and the children and young teens who gather there exert their own irresistible pull. And I wanted to see how the song was going to turn out (though I didn’t foresee it was going to take 11 weeks before it was ready to be performed). It also felt important to find out how Trump and his government were actually affecting the children. What was it like for a young brown girl to know that the “most powerful man in the world” had hurled crudely bigoted insults against her family’s nationality, her race—deriding Mexican migrants as criminals and rapists—or to have to live with these new threats against the integrity and safety of her family, much more direct and ominous than any she and the other children might have heard or picked-up on before, certainly living in Bushwick? Were those children already being harmed, and if so, in what ways?

I suppose I was hoping for glimpses, passing insights; you couldn’t expect an eight-year-old to have processed something like that into a fully conscious and articulate understanding of what was being done to them, could you? Especially when, across the land, plenty of highly educated adults were still reeling in confusion over the new national reality. But it was going to take more than a couple of weeks to write that song, which, I soon realized, was also going to be an explicit working out and expression, individual and collective, of what those kids were experiencing.

Stephen Haff and the Still Waters kids get to work on the Quixote Project.

Stephen Haff and the Still Waters kids get to work on the Quixote Project.

Over the next 11 weeks I came nearly every Monday night to Still Waters with my wife Jovi to watch and listen as the children—guided by Stephen and Kim Sherman, the multi-genre composer of the musical O Pioneers, and of other choral works—slowly built their “Rescuing Song,” collaborating on the lyrics and music, drawing on their reading discussions and translations of Don Quixote, along with shared stories and thoughts about their own lives. I hung on every word, riveted to their conversations, and also, I always found, transfixed by the facial expressions of those children tightly gathered around a long table as they spoke, listened, mused, agitated for Stephen to call on them next, or just let their minds wander. That core group of Quixote kids included Jamie, Leslie, Jonathan, Elias, Michelle, Natalia, David, Sarah, William, Bryan, Bryant, Kimberly, Keyla, Jason, Jaylee, Aylen, and Amelia. As the weeks passed, the beautiful chorus, with its C, A minor and F chord progression and hymn-like melody, became a part of my life; all day long I found myself humming or singing from it. Walking to the subway, Jovi and I sang it out loud.

The Saturday sessions at Still Waters are attended by many more neighborhood children, and parents (usually mothers) bring food they’ve cooked at home—it’s also when famous writers visit. The likes of Richard Price, Zadie Smith, Michael Ondaatje, Peter Carey, Claire Messud, and many more have garnered Still Waters most of its publicity and helped spur fundraising (most recently Monica Lewinsky came to talk about bullying—“the kids loved her,” Stephen wrote to me). But it is the school week sessions that demand the most commitment from the children and their families—these comprise the real laboratory for Stephen Haff’s wizardly adventures in collective learning and creation. For these children, it is the norm to wake at dawn for six-and-a-half to eight-and-half-hour schooldays at public or charter schools. Schooldays are followed by at least two hours of homework, which they often come in to do at Still Waters, where Haff and other volunteers help out.

Wednesdays and Thursdays Haff gives classes in Latin—the blackboard at the front of the room has chalked conjugations of the Latin verb to love, Amo Amas Amat Amamus Amatis Amantor—and this year they’ve also been studying ancient Roman history, along with reading Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis. Thursday evenings the students form small groups for creative writing workshops led by volunteer writers and MFA students; for four years, I mentored a small writing group of girls, beginning when they were seven and eight, getting to work with some of them—Jannethy and Betzi, always writing her hilarious stories about a character named Sushi Man—into their early adolescence. By five in the afternoon, when the Quixote workshops usually start, the children are tired, hungry, or feeling pent-up and restless—even in the cold, the boys and some of the girls kick a soccer ball around on the sidewalk until Stephen calls them in. Nachos and avocado delivered from a local restaurant arrive at the start of each session to help fuel them for the last hours of their long, demanding days.

![]()

But that first Monday the “Rescue Song” still didn’t have a single lyric, or a melody, or a refrain. In other words, it didn’t exist. There was only an idea for a song about rescue, inspired by Don Quixote and by the students own lives. The immediate challenge, Kim Sherman explained to them, was to get to work building rhymes by bringing words from the novel into the song, or words of their own. To work from, they had, first of all, the image of the farmer lifting the beaten Don Quixote from the ground. Le limpia el rostro. The farmer cleans his face, so covered in dirt and dust that Don Quixote is unrecognizable. One moment of kindness. Stephen said, “Come up with a refrain that ties it all together. What is the point of view of the song? Is it, I saw this thing happen?” He drew their attention to the passage where Don Quixote, newly embarked on his quest, thanks heaven for the opportunity to be a chivalrous knight and rescue someone, or help someone.

“The refrain will come from Don Quixote,” Stephen told them, “and the verses will be your story.”

The children sitting around the table that afternoon came up with plenty of ideas for the refrain:

“Gracias doy al cielo.”

“I promise to make more care with the sheep.”

“Shameful to beat someone who can’t defend himself.”

“Sometimes you have to pick up your lance and fight.”

And Keyla offered, “Make them feel they belong here and make them feel happy.”

“Awake, arise or be forever fallen,” said Bryan, grinning proudly, lifting his head so that his eyeglasses shone with light. Those words are from Milton’s Paradise Lost which Stephen and the children had studied together at Still Waters last year.

Natalia gets ready to recite her part of the play the children have adapted from Don Quixote.

Natalia gets ready to recite her part of the play the children have adapted from Don Quixote.

The children pored over their photocopied pages of refrain ideas and suggestions they’d come up with the previous week. These included such phrases as, “I will help you,” “I will protect you,” “They don’t have a voice,” and “Imagine a world.” Then everyone voted for the ones they liked best: the top five vote-getters included, “Feel deep in your heart to help,” “We will make you feel you belong here,” and, finally, “Can we help? Can we help?” (Two months later, when the song was finally finished, Kim would recall the moment 15-year-old Leslie, with an air of tender gravity, had come out with these latter words, spoken in the rhythm of the refrain they became.)

Can we help, can we help, can we help. In C, A minor and F, repeated three times. Followed by:

We will protect you with our song.

Can we help, can we help, can we help.

We feel deep in our hearts you belong.

By the end of that Monday class, though still without music, the refrain had come into existence, inspired by the passage about the farmer who wipes the dirt from Don Quixote’s face, and by the children’s own sense of threatened safety and tenuous belonging.

“What you’ve made is brilliant and beautiful,” Stephen Haff told them just before the session ended 6:30, when the mothers, mostly, and other relatives began arriving to pick the children up and take them home.

![]()

The following Monday began with Stephen Haff discussing recent news reports of ICE grabbing immigrants out of court houses, and how immigration lawyers and activists were advising immigrant families to not answer the door should ICE come seeking entry. It was stomach-churning to watch as the children listened to Stephen, the fear and worry filling their eyes. I almost wanted Stephen to stop, though understood it was necessary advice he was sharing, advice that people have to hear over and over until it becomes automatic, practically instinctual: Do not answer the door.

Over that Monday’s session and the next, the first verse of the “Rescuing Song” came into being. We all listened as Stephen read the extraordinary monologue in Don Quixote of the beautiful shepherdess Marcela, who defends herself against the male shepherds who blame her for the suicide of lovesick Grisóstomo, whose unsought love she had spurned.

Of those shepherds, Leslie said, “They don’t love her, they want her body, not her soul.” The class had already decided that the verse should be told from the point of view of immigrants like themselves and their families, and Stephen had them write brief monologues. If they could speak to Cervantes, what would they want him to understand about them? Afterward, the children read their monologues out loud.

“I want you to understand we are a united family, we have to take care of each other. You’re building a wall but tearing down laws.”

“I’m confused and praying all the time without knowing what’s going to happen tomorrow.”

“I did not cross the border, the border crossed me. If you don’t want us to come stop glamorizing your country around the world. Stop promising me things then threatening me.”

“I want you to understand that life is difficult these days. I am an independent girl with a little sister.”

“I am a woman with two children and I have a family that is suffering.”

“Here I am at the wall face to face. I want you to understand that my dream is being stopped. I can’t have my opportunity. The opportunity to be with my family. To have an education. To become who I want to be when I grow up. I can’t because of the wall.”

“13-year-old child with a 9-year-old sister. I have a family, I want to see my family, I’m trying to flee my country. We are at war and I’m just an innocent bystander watching everyone die, waiting for my death as I’ve been sent back.”

In their monologues they told Cervantes what they wished Trump and the rest of the United States would understand.

“Good rhyme,” Kim had taught them, “happens when you land on the right place with the important words.” She explained musical rests between words, and silent beats. Their emerging song was in 4/4 time, 4 beats to the measure. The verse, and the song, now had its opening line:

I beg you to understand me, to listen to my voice.

The first and third beats were the strong ones.

Then Kim held up some sheet music and told the class she’d been working on the melody. “It’s a first draft,” she said. “This will be 10 percent writing, 90 percent rewriting. Do not fear the rewrite. Now we’re starting to put words to notes.”

They discussed how they wanted the music to feel, and Jamie, 14, who wants to study music and sings in a choir, said, “I would keep it mezzo piano, we need it to be soft to show the message.” The refrain, they decided, could move in a different way than the verse. Leslie said, “The refrain can have a faster tempo, urgent.” Kim played the melody through for the first time, and when she was done, everyone applauded.

Jonathan made the second line of the verse he’d come up with fit the melody by simply adding the word, here.

I’m not asking to be revered here.

He explained, “We don’t want to them to love us, but to understand and accept us.” It was Jamie who then came up with an astonishing revision in Kim’s melody, suggesting that that line begin on a minor chord, E minor. Michelle agreed and said, “Minor makes the song more sad.”

I just want to have a choice.

That’s the next line of the verse, repeated twice, the second time—this was Leslie’s idea—with the notes rising. “It’s so beautiful when it goes back up again,” she said. And Jamie, who has a quiet, seemingly aloof punk demeanor but never misses a thing, said, “The beginning should be quiet and then shift to forte, it sounds great.” Leslie: “Invite them in quietly.”

Stephen wanted some verses to be in Spanish. “Right now,” he said, “people and families are being separated. Your language is part of that. There are people who think only English should be spoken here. We need to hear immigrants speaking their own language.”

And that was how, Por favor, entiéndanme became the next line of the verse.

“This is the hard part,” said Kim, by which she meant completing the second half of the verse. “Now we have to match this structure.” She spoke about the challenge of writing “towards the rhyme,” rather than just writing a phrase you like and trying to tack on a rhyme. Revere, here, fear—they’d nailed those rhymes. Now everyone wanted find a way to emphasize “wall.” Maybe it could be rhymed with “fall.” The idea of falling and getting up, the way Don Quixote and Sancho always do.

Leslie said, “People who are racists and who are against immigrants have walls in their brains.” Right after that, always cheerful Brian said, “Ignorance builds a wall.“ And then Leslie added, “They give you like two hours to pack up and leave everything you’ve established.”

Ignorance built this wall.

Now they had the next line of their verse.

But they needed something to rhyme with “wall.” It was getting late, there were only minutes left in the class. But nobody wanted to go home without finishing the first verse. “We’re all family after all.” “Don’t let my dreams fall.” That was when seven-year-old Sarita chimed in with, “My family is the best of all.” Which she quickly amended to, “My family is MY best of all,” a radiant, pixie grin showing up ear-to-ear. It was almost magical, the way it clicked and everyone knew. One last change: they decided on mi famila for the beginning of the line.

Ignorance built this wall,

I don’t want to live in fear

Mi familia is my best of all

Followed by the refrain:

Can we help, can we help, can we help

As she waited for her mother to arrive, Sarah, who’d saved the day, sat at the upright piano playing with two fingers while balancing a plastic pencil case on her head. Kim sat down beside her and began to teach her how to play with her third and fourth fingers. “Next time I came in” Kim recalled later, “I found Sarah sitting there playing the way I showed her.” Another time Kim found Jonathan sitting at the piano playing Tchaikovsky. He had never taken piano lessons. “He’d just figured it out,” said Kim. “That guy’s just got an ear.”

![]()

The following Monday, Kim started class by explaining that the second verse would be even more of a challenge because it had to match the structure of the first.

William, a fidgety seven-year-old wearing plastic turquoise glasses that looked like swimming goggles, couldn’t stop looking through his pile of Pokemon cards, and Stephen said, “I’m not going to spend the whole class saying ‘William put the cards away.’” It’s sometimes hard to keep the attention of a room full of children who’ve already been in school all day, and Stephen’s extraordinary stream of pedagogical discourse, cheerleading, cajoling, inquiry, guidance, confiding, listening and more listening, is punctuated too by incessant, sometimes scolding, tugs at the children’s attention—“Sit up… pay attention… stop talking… look at me”—that provide a kind of running syncopation to the sessions, provoking chastened smiles, and tired eyes forced opened in willed alertness—and occasionally a fleeting moment of sullenness over a little scolding. Several of the Still Waters mothers I spoke to told me they admired Stephen’s strictness, and the way he teaches their children to listen.

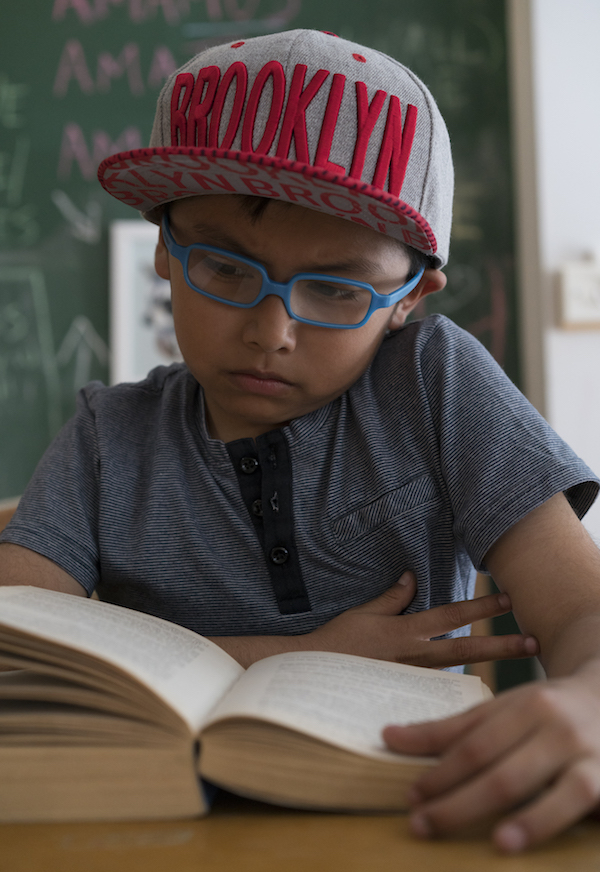

Seven-year-old William reads before the start of play practice.

Seven-year-old William reads before the start of play practice.

Minutes later, as the class was discussing how to translate a passage from Don Quixote that begins Déjate de eso y saca fuerzas de flaqueza, Jonathan came up with, “Stop whining and find strength in your weakness and I shall do the same, and let’s see how Rocinante is doing because it seems like he received the short end of the stick.” Goggled, antic William quickly interjected, “That is an idiom! I learned that word in school. Like if you say, That is the last straw, that means, the last time. That’s an idiom!” Another student couldn’t remember where in the novel that speech occurred and William responded right away, “It’s when Don Quixote goes charging through the sheep and the shepherds throw rocks at them. The horse got the worst of it.” From where I was sitting I could peek into the book bag into which William had obediently put his Pokemon cards, and I saw it was stuffed with two thick copies, each well thumbed, of Don Quixote, one in Spanish, and the other Edith Grossman’s English version. (One afternoon a few weeks later, I’d hear William exclaim about Don Quixote, “He loves words because he reads too many books, just like me!”)

Siempre deja la ventura una puerta abierta en las desdichas, para dar remedio a ellas.

Jonathan held up his phone, he’d just Googled the somewhat antiquated word, ventura. “Fortune,” he said.

Fortune in what sense? Stephen asked the others.

David: “A lot of money.”

William: “Luck. The future. Good academic success.”

Jonathan: “Fate.”

Kylee: “Magic.”

Michele: “An open door.”

And desdichas? asked Stephen.

Jonathan: “I’m thinking ditches.”

“Stop crinkling the cellophane,” Stephen called across the table at William, who’d reached for the cookies. “So, fortune always leaves a door open in misfortune,” he went on, “para dar remedio a ellos.”

“Remedio, to give medicine,” said Kimberly.

Leslie: “To give remedy to misfortunes.”

William: “Falling into volcanoes!”

Fortune leaves a door open to give remedy to misfortunes. “They keep believing that if they get up again and again and keep going,” said Stephen, “things will get better.”

From a hilltop, Don Quixote mistakes the flocks of sheep he sees for armies. Sancho of course only sees sheep. And this brilliant little boy, goggle-eyed William, said, “Don Quixote is telling Sancho, You’re afraid to face the truth. That’s irony.” In his prologue to Grossman’s translation, Harold Bloom wrote that Thomas Mann especially loved Don Quixote for its ironies.

Leslie clapped her hands to her head, and groaned, “It’s his reality.” Then she wondered out loud if Sancho was being a good friend or a bad one in not insisting to Don Quixote on the truth about the sheep. Does a good friend, she asked, indulge a crazy person? Recently on Spanish language television she’d watched a show in which one teenage boy says to another, Stop doing drugs, or else I’m not going to be your friend. “Is that really being a good friend?” Leslie asked. Harold Bloom, contrasting Don Quixote’s protagonists to the soliloquists of Shakespeare’s plays, describes the relationship between the mad Knight and his squire as literature’s unsurpassed portrayal of friendship, though it is a relationship, as both William and Leslie perceived, of ironic and often painful complications.

Stephen jokes around with Sarah in the afternoon light.

Stephen jokes around with Sarah in the afternoon light.

The second verse of “The Rescue Song” directly addresses immigration. The children went back to brainstorming over their printouts of passages from the novel to translate, refrain ideas, their own monologues… they also tried out some new ideas. “I came here to have a better life and get away from the gangs.” “Create an ocean. Not a dam.” “I might be different than the people who came here, but…”

But when Jonathan said: I came here to seek protection, the second verse had its first line.

Everyone agreed, initially, that the word “life” should set up the next rhyme: I came here to seek protection, to look for a better life, something like that. But Stephen warned that a line about coming in search of a better life was kind of cliché, and asked for something more specific.

“Why are we pointing out that we’re different?” asked Leslie. “What are we implying? We do live here.”

“The first verse is establishing, I want you to understand me,” said Kim Sherman. “Like, I want to have a fair shot.” What should the second verse say? Someone suggested replacing “life” with “night,” which could be rhymed with “fight” or “flight.” Kim sang, “Lalalalalala night,” and Keyla’s head bounced along. Leslie said, “Escape through the harrowing night.” Stephen, who wanted to find a way to evoke Emma Lazarus’s Statue of Liberty poem in the song, suggested, “Huddled masses in the night.” That immediately evoked for Leslie one of the iconic experiences of Latin American immigration to the US border, the kind of journey undertaken by so many of the Still Waters kids’ parents and other relatives: “The people are very close together—they are in a truck, are one body and are all together.” One of the two girls sitting together, both wearing eyeglasses, either Natalia or Michelle, I didn’t register which, enunciated the phrase, “I traveled through the night.”

Kim asked the group what feeling they wanted to express in the verse, and Jonathan answered, “The sadness you felt when you left your country. Sadness, melancholy. Also, deportation results in depression.” Leslie said, “Describe the setting of where they’re going through, you know, the desert, the eagles flying by.” Brian suggested, “Trump is deporting people and people are running away.” Leslie responded, “No, adding his name to the song, ugh.” “Yeah,” said Jonathan, “putting his name in would create a wince.” Keyla: “It would make people ill.” Stephen Haff again suggested using some Statue of Liberty language, something about coming for opportunity maybe, but Leslie said no, that was too general.

That Monday, in a way I hadn’t quite heard them do before, the Still Waters kids voiced anger and disillusionment with the country where most of them had been born, though their parents hadn’t been. The relentless news of aggressive measures against immigrants, the wall, the random arrests and deportation, even of mothers without criminal records… all of this was having an effect, and was clearly getting to some of them.

“People want to be citizens,” said Jonathan, “but they still love their country of origin, you desperately want to stay there but you can’t. A word like country, it can carry so many different meanings.”

“But if someone comes here fleeing gang violence,” said Kimberly, Leslie’s younger sister, “they don’t want to go back.”

Jonathan insisted, “Or else they want to build something and go back to Mexico. We can’t just state one reason, we have to state all.”

Leslie said, “When you come here it’s because you have to. But it doesn’t have to be one or the other, both are your real homes.”

Aylen, 14, poised and thoughtful, said, “I don’t know what side of the wall I belong on. Part of me is here, part of me is elsewhere.”

“Lady Liberty,” said Leslie, “why are you claiming her if you haven’t met her yet?”

Jonathan said, “What is that light that has gone dark.”

“The sun, the sun could kill you. Remember the farmer wipes the dust off Don Quixote’s face,” said Stephen, and asked for another phrase in Spanish. “The Latin root for the word translate is to carry across,” he said. “Carrying the meaning across. Crossing borders, all of this is about carrying across.”

Keyla repeated:

I traveled through the night.

The verse, which drew on their discussion, and followed the structure of the song they’d constructed in the first verse, now began to come together.

Adios, preciosa patria.

Found myself in burning light.

Burning burning desert light.

Seven-year-old Sarah exclaimed, “Burning light is like Tyger Tyger burning bright!” She was remembering the William Blake poem they’d read at Still Waters last summer.

“What comes next in this story?” asked Stephen.

Jonathan said, “America’s potential kindness.”

We were again running out of time, grappling and grasping for the end of another verse. What comes next in this story?

Sarah: “They saw a tiger, or a coyote.” Suddenly the seven-year-old girl was telling us the story her mother had told her about how she’d come to this country riding in a truck with animals, and how she’d come across the border on the back of a tiger.

Someone crossing into the USA on a tiger! What a great ending to the second verse that was going to make! Everybody went home smiling over Sarita’s magic realist epiphany. But, apparently, at the next Monday night session—that was one I missed—they just couldn’t find the rhyme. But the spirit of Sarah and her mother’s story did survive in what would eventually be the last line of the verse:

Nobody wants your throne

We’re not going to steal your gold

But innocence needs a home.

![]()

In the three weeks since eight-year-old Keyla began being tutored in reading at Still Waters, her reading level at her primary school had risen from H (well below 2nd grade) to M (beginning 3rd grade). Michelle rose from the middle to the top rank, number one, in her 6th-grade English class. Rachel, Jamie’s 16-year-old big sister, told me that if it hadn’t been for Still Waters, she was sure she wouldn’t have gotten into the High School of Art and Design, where she is now studying graphic design.

An eighth grader, Jamie had recently taken entrance exams for La Guardia, Brooklyn Tech, and other demanding schools. Her mother, Andrea, told me that her daughters’ vocabularies had expanded after coming to Still Waters. “I can help them up to a point,” she said, “but then my own English fails me.” Andrea said that her daughters’ perspectives of other people had also expanded at Still Waters, that they’ve learned everyone deserves respect.

Kimberly (green shirt) and Emanie relax before play practice begins.

Kimberly (green shirt) and Emanie relax before play practice begins.

“It’s a safe place,” she said, where she can leave her children without any worries during her own long workdays cleaning houses in Manhattan—most of the Still Water mothers I spoke to work as housecleaners in the city. It’s not as if Still Waters is the only place where children from immigrant families can get help with their homework while their parents work in the afternoons, but, Andrea said, “The other places don’t have Stephen.”

Jamie told me that since coming to Still Waters her class participation in school has also improved, and she’s begun feeling less fearful of expressing her thoughts; her reading and writing have improved too. “Before, in my writing,” she said, “I was very basic, I didn’t have details.” She would just write that it was a tree, she explained, not that it had apples, or that it was green. Her stories started getting longer, with more detail, and the teachers at her school noticed.

Bryan’s mother, Maria, from Ecuador, at first thought Still Waters was a bookstore: whenever she passed by on Stanhope Street the sill of its front window would be lined with books. She enrolled Bryan when he was seven. Two years later, she told me, she’s noticed great changes. Bryan has become more disciplined and organized. “In school, he speaks up now and answers questions,” she said. “Before he used to be very timid.” He’s learned to listen to other people, she stressed, and added that, “Before, he didn’t like to read.” Now he’s become a nine-year-old boy who goes around quoting from Paradise Lost. “Stephen has a magic wand,” said Maria. Even on days when he doesn’t have school, Bryan comes to Still Waters in the afternoon to study. Bryan’s mother has been cleaning houses in New York for 12 years, and her husband works in construction. By saving money and taking out loans in Ecuador, they’ve recently been able to pay for their two older sons’ long journeys to the US to reunite the family. Both sons are already working—one wants to save his money so that he can return to Ecuador and continue his university studies in engineering. Maria told me that she feels blessed. Yet she knows how suddenly it could all end.

There’s always something to read at Still Waters in a Storm.

There’s always something to read at Still Waters in a Storm.

There is no application process for Still Waters. Stephen says that people just bring their kinds by and “if I’m not overwhelmed I let them in.” But usually there is a waiting list of a hundred children. “I call them when there’s room,” he explained, “But I also let some in when there’s a family or friend relationship. Meaning when I’m already working with their cousins or neighbors. This tends to bring stability to the group.”

![]()

What do children need? That was going to be the subject of the third and final verse. Once again the children shared ideas and made lists. Children need nachos, the city, freedom of expression, nature, shelter, family, food, friends, rights, safety, imagination, respect, (McDonald’s and Burger Kings according to Sarita), bedtime stories, hugs, bikes, responsible grownups…

Leslie said that as the song’s first verse began with the children begging to be understood, this last one shouldn’t have a begging tone, it should be stronger. “Something that says, I pick you,” she said. “A gesture, hold my hand.”

Hold my hand please, and save my childhood.

“Together” would be the first word of the next phrase—but together what? Together we can “fight.” But then Kimberly suggest it should be “play” rather than “fight.”

Together let’s go play.

“Pretending to be heroes is the best kind of play,” said Leslie. “We always save the day.” Let’s pretend that we are heroes became the song’s next line. And then Sarah chimed in:

We are here to save the day.

Always here to save the day.

Por favor entiéndanme!

And then came this suggestion:

Responsible grown-ups, listen to me!

“Yes, I like it, let’s do it!” exclaimed Kim after some discussion, though “responsible grown-ups” would have to be somehow “shmushed” into a single beat. A chanted command from the children demanding to be paid attention to, to be noticed. (Later, on April 19, when they performed their song before a nearly packed house at Symphony Space, the way they sang Responsible grown-ups, listen to me! had the pluckiness of It’s a hard knock life and provoked a wave of laughter from the audience.)

Somos niños no nos ven? (We’re children, can’t you see?)

Déjanos ser feliz. (Let us be happy.)

Followed by the final Can we help repeated three times, with the second and fourth lines of the refrain:

We are reflected in your eyes

Come across, reach the lost paradise.

Stephen had told the class that day about how his four-year-old daughter, looking into his eyes, had exclaimed, “Daddy, I see myself in your eyes.” Jamie reworded it into the song lyric, and said she was thinking about how the immigrant often sees herself reflected in the other’s eyes.

The spoken-word bridge, inserted between the second and third verses but composed afterward, brought back words the kids had already translated from Don Quixote, including, Siempre deja la ventura una puerta abierta, which Jamie said should be recited in a staccato. And Stephen Haff got his wish as Emma Lazarus’s Give me your tired, your poor, made it into the bridge as well. Though no one liked having to say those words, wretched refuse.

Three verses, and three choruses in which the second and fourth phrases vary, and a spoken-word bridge before the final verse. A four-minute song. On a Monday afternoon in mid-April, the Still Waters Quixote Project kids all gathered to sing and rehearse the full song for the first time. Several times they sang it from beginning to end, in every version their voices growing stronger. Then we all applauded.

Kim told everyone, “This thing that you made is now a song, and it exists, and it’s like it was always there. Wow. This is a thing.” And Stephen Haff said, “It came from Don Quixote and all the conversations we had about it and from our own stories, everything we’ve worked on this year, in a song. And it’s beautiful.”

__________________________________

All photos by Rachel Cobb.