Visiting a Secret Museum in the Middle of the Uzbek Desert

Creating a Refuge for Art Targeted by the Soviet Regime

The world’s second-largest collection of Russian avant-garde paintings sits in a relatively unknown museum in the middle of the desert in Uzbekistan. According to some, this is no coincidence. The museum’s origin story, as presented by a smattering of Western media outlets and travel books, goes something like this: a brazen collector amassed the collection as an act of dissidence and then hid it in a remote museum where no one would think to look.

Something about this story gives me pause. So in Khiva, I search for a taxi to take me three hours into the desert.

*

In 1966, Igor Savitsky opened the Nukus Museum of Art in a remote city in the Uzbek desert. Nukus was small, obscure, and hard to reach, making it an ideal location for a nuclear testing facility or a secret underground lab, and a less logical place to put an art museum.

Unless the point was to keep certain people from visiting.

The Soviet government didn’t take kindly to abstract art or the people who made it. During Stalin’s purges, almost anything could be used as an excuse for arrest, including and often especially writing, thinking, and painting things not sanctioned by the Communist Party.

But this party, along with the government it ran, was headquartered in Moscow. To the Soviet leaders, Nukus was far away and not particularly important, and no one in the Kremlin was paying close attention to the city or a tiny museum inside it.

And so the museum became a refuge for art persecuted by the Soviet regime. Savitsky salvaged thousands of works hiding in basements and attics, waiting to be destroyed or forgotten, and gave them a home in his museum. In the end, art triumphed over tyranny. It’s a great story. Maybe too great to be true.

The museum’s origin story bothers me because it’s too simple, too clear-cut. It’s missing the messiness and moral ambiguity of real life. I worry that it’s a convenient backstory for a museum in an inconvenient location.

I want to believe in abject heroism in the face of tyranny, but valiant deeds seem more often stumbled into than carefully premeditated. You don’t start out planning to save a thousand people from Auschwitz. You begin as a Nazi industrialist with a factory.

Did Savitsky go to Uzbekistan with the intention of risking his life to save art? Or is his legacy something that happened along the way?

*

I find a driver who will make the three-hour journey to the museum. He’s a reticent man who stops before we leave town to stock up on a frozen snack called “ice milk.” I hope, for his sake, that’s a mistranslation.

Outside the city, the land empties into open vistas of sky and sand. The same unchanging reel of brown desert and scruffy shrubs cycles past our windows. Clouds hang low in the sky and swirl above our heads.

I wonder whether I’m going to a place Savitsky went in order to save a bunch of paintings, or a place where he happened to be living when he had the idea to open a museum.

It quickly becomes a long ride.

*

Igor Savitsky was born in Kiev in 1915 and grew up in Moscow in the years following the Russian Revolution. As a child, he dreamed of becoming an artist. He took painting lessons while he was young and enrolled in art school as an adult, though perhaps as a backup plan, he also trained as an electrician.

In the Second World War, the art institute at which Savitsky was studying was evacuated to Samarkand. He spent the war in Uzbekistan, and returned after completing his studies to work on a major archaeological excavation in the desert region of Khorezm. There, he studied artifacts and folk art created by the Karakalpak people. In his free time, he painted landscapes of the sandscapes that surrounded him. He still clung to his dreams of making great art.

A few years later, Savitsky returned to Moscow with his paintings of Uzbekistan. He showed them to Robert Falk, a prominent Russian painter whom Savitsky greatly admired. Falk declared them to be terrible.

This was a huge blow to Savitsky. Devastated, he cut up his canvases. He decided that he was finished with the Moscow art world, and he returned to Uzbekistan. He settled in the small city of Nukus, where he continued his work in archaeology and ethnography.

There, Savitsky began collecting art and artifacts of the native Karakalpaks. He amassed jewelry, headdresses, pottery.

At some point, he decided he wanted to open a museum with his Karakalpak collection. But the Soviets tended to be skittish on cultural heritage, seeing it as a dangerous weapon groups could rally around to question the authority of the Union.

It’s said that Savitsky browbeat local authorities into giving him his museum. Or maybe Moscow was far away and didn’t feel particularly threatened by an exquisite collection of earrings.

Either way, Savitsky opened his museum in 1966.

And then he began collecting paintings.

*

The Nukus Museum is a blocky space-agey building that looks like the losing entry in a 1969 design competition for a public library. This could, I suppose, be intentional.

When the Bolsheviks came to power, they brought with them ideas of what art should be. It should be easy to understand and relevant to people’s lives. It should glorify the worker and support the state.

By 1934, the Soviet government had issued a list of standards to which it declared all art should aspire. It had to be proletarian and realistic, it had to represent scenes of everyday life, and it had to support the aims of the state and the party. Art that met this criteria was “approved”; everything else was not. An exemplary piece might depict young, rosy-cheeked communists smelting iron with joy. Abstract painting, a category into which almost all of the avant-garde fell, was now condemned as bourgeois and decadent.

“I want to believe in abject heroism in the face of tyranny, but valiant deeds seem more often stumbled into than carefully premeditated.”

Artists who failed to conform to official tastes were removed from their jobs and barred from exhibiting, or arrested, or worse. Some left. Chagall and Kandinsky took refuge in Europe. Malevich stayed behind and had his paintings confiscated. There are doubtless other names we’ll never know, either because they chose to live by painting smiling iron smelters, or because they didn’t.

Within the Soviet Union, the avant-garde movement withered and died.

Except, the Nukus Museum of Art asks, what if it didn’t? What if some artists kept painting subversive work in secret? What if they hid the results in places where they’d never be found? What if the events that seem most improbable unfold in ways that make it look easy?

*

At the ticket counter, I notice a sign offering a private English tour of the collection. I do the math and realize it costs $5 U.S.

A few other foreigners mill around in the lobby holding tickets or reading guidebooks. Why, I wonder, is no one else booking the private tour? Maybe it’s terrible. Maybe all of their guidebooks warn, “Whatever you do, don’t take the $5 private tour!”

I’d kind of like to explore the museum myself, but to not ask about the $5 private tour feels like declining the gift horse without even looking it in the mouth.

I ask the woman behind the desk if there are any English tours today. I’m kind of hoping she’ll say no and let me off the hook. That way, I’ll be able to say I at least asked about the $5 tour, and I’ll console myself by reasoning that if you book a private tour that costs less than the average sandwich, you probably get what you pay for.

To my dismay, she says there is.

“Is it starting soon?” I ask nervously.

She frowns and tells me to wait. She disappears behind a door and then returns, nodding.

“She can do it now,” she says.

*

Some of the first paintings Savitsky purchased were by a Russian artist living in Uzbekistan named Alexander Volkov. Once a distinguished painter awarded the title People’s Artist of Uzbekistan, Volkov had fallen from grace after Stalin ramped up the campaign to replace abstraction with Socialist Realism. Volkov’s paintings were labeled “counter-revolutionary” and removed from museums. He was fired from his teaching post. He spent the remainder of his life in isolation, prevented by the local artists’ union from having any contact with the art world.

Savitsky bought his first Volkov paintings a decade after the artist died. This acquisition inspired Savitsky to travel around Uzbekistan looking for “art that the history of our times condemned to obscurity.”

But art isn’t always condemned to obscurity because it’s subversive. Sometimes, it fades into obscurity because it’s not that great.

*

My guide’s name is Gulmara. She’s quiet and thoughtful, and she knows the history of the museum and its paintings with a thoroughness I’ve never achieved outside of the biographical details of members of ’90s boy bands.

Before we enter the collection, she makes me leave all of my belongings in a locker.

“Can I bring this?” I ask, holding up my phone.

She shakes her head.

“This?” I hold out a notebook and pen.

She considers, then decides it’s allowed.

Gulmara’s caution may have something to do with the museum’s director recent resignation, which took place in the midst of a murky controversy. The government alleged that the director had been forging paintings from the archives and selling the originals to wealthy collectors. Her supporters allege that the government fabricated this story in order to push her out, so that it could quietly implement this exact scheme.

Gulmara does not tell me any of this, but she does, in one rare, unguarded moment, declare how much she admires the former director, her former boss, and she says this with such fierce intensity that I would want to believe her even if evidence pointed to the contrary.

Paintings cover the walls from floor to ceiling. No inch of wall space is wasted. In some rooms, the art feels less on display and more just really jammed in there. There’s a sense of urgency, a need to exhibit as much of the collection as humanly possible.

After his Volkov purchases, Savitsky spent the next 20 years traveling around Uzbekistan in search of paintings that had been hidden in attics or stashed in the back of closets for fear of getting their creators labeled counterrevolutionaries. Sometimes, the paintings’ “subversive” qualities were limited to abstract forms. Other works were more explicit in their critique of communism, the Soviet government, and the way of life in the USSR.

Savitsky undoubtedly saved some work that would otherwise have been destroyed, but he might have just set out to collect paintings, not preserve a piece of a modernist movement. Unapproved work that couldn’t be shown in official galleries might have been easy to acquire. So could paintings that no one else wanted.

When people say Savitsky hid the paintings in the desert, they usually don’t mention that the desert was also where he happened to live.

But now I’m starting to question how much that matters.

*

Here is an expressive, chaotic canvas in which forms bleed into the shapes beside them.

“It’s a caravan,” Gulmara tells me.

Here are landscapes, deconstructed; faces, chopped up and reassembled; portraits barely recognizable as such; here are vibrant bursts of color, scenes of daily life; here is a woman, here is a man, here is a mood, idea, intimation. Here is a collection of art that overwhelms the space it’s in; here are portraits, stacked five on top of one another, covering the walls, leaving barely any white space in between, hinting at the hundreds or thousands of more unseen in basement storage.

Here is the collection’s pièce de résistance. It was painted by a man named Vladimir, or maybe Evgenney, Lysenko, an artist about whom little is known, except that he was arrested and probably died in a mental institution, possibly not because he suffered from mental illness, but because the authorities wanted to keep him from painting.

The painting is titled The Bull. A secondary title is, apparently, Fascism Is Approaching. It’s hard to find much information on the piece. Some sources use the second title; others only the first. It’s unclear if the artist gave the work its politically charged name, or if that was added later. It’s unclear when it was made. Most of all, it’s unclear why, without the second title, it would be considered so slanderous by the Soviet government.

Especially given how openly the other paintings brazenly mock and disparage the powers that were.

Here is a painting called Drink to the Dregs. Do I see the influence of German expressionism? Look at the caviar label pasted onto the canvas. This was a luxury brand favored by the political elite, who lived private lives of lavish comfort while publicly condemning decadence. Do I see the political critique?

Here is another canvas, called Capital. A grotesque couple smile in front of a backdrop of floundering workers, the couple’s material comfort apparently built on the backs of others’ labor. Gulmara tells me that the work is only the top half of a larger painting. The bottom is missing.

“Is there such as thing as objective aesthetic value for art made under duress? Does it get graded on a curve?”

Many of the works were painted on top of existing pieces, because, at that time, it was cheaper to buy an old painting than a blank canvas. To get a sense of what was underneath, the museum staff X-rayed the pieces at a hospital in Nukus.

Some of the paintings compel me to keep standing in front of them after Gulmara finishes her explanation. Others don’t, but sometimes I pretend to be absorbed and enthralled, because I want Gulmara to feel like I love each painting as deeply as she seems to, that I, too, am reveling in the precise, meticulous details she shares with me.

I’m trying to discern if these paintings were on the verge of being forgotten because they were forbidden, or because they weren’t particularly memorable to begin with. I feel guilty wondering about this, because being here has made me realize how difficult it must have been to make art during the Stalinist purges.

Is there such as thing as objective aesthetic value for art made under duress? Does it get graded on a curve? Do the paintings left behind preserve the story of the risk and sacrifice required to make them, and hint at the works that were never painted? Would that story have been conveyed if I’d just wandered through the galleries, staring at the paintings unguided?

*

Here is one way to understand the story of Savitksy and the Nukus Museum: a failed artist built a collection of works by artists who similarly failed to gain recognition. Here is another: a man had a vision to preserve endangered art in the middle of the desert.

The result is the same. Savitksy put together the world’s second-largest collection of Russian avant-garde work. The only one that surpasses his is in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, a massive collection in a city known for its mind-numbingly massive collections. This makes Savitsky’s accomplishment impressive regardless of how or why it happened. How many private collectors assemble a catalog that rivals that of a state museum of the largest country on Earth? How many fewer did so without access to ample funding, by simply persuading artists and their families to give him work that they didn’t want?

This is where the collection is most vulnerable to criticism. Some argue that Savitsky’s collection dates from a period when the avant-garde was in decline, and that it lacks works from the movement’s most well-known artists. Art critics have said that the pieces in the Nukus Museum are, for the most part, unremarkable.

But it must have been hard to become remarkable when you couldn’t learn abstract techniques in schools or study at the movement’s masters in exhibitions.

One of the last paintings Gulmara shows me is a bright, happy scene of a family at a picnic. A blanket spreads over the ground, and Gulmara points to the baby in the center of it. She smiles. “That’s me.”

At first, I’m confused. She feels like a picnic?

No, no. “My father was one of the artists in the museum,” she tells me.

The pieces click together.

“Do you tell everyone on the tour?” I ask her.

Her smile becomes more mysterious. “Only some.”

__________________________________

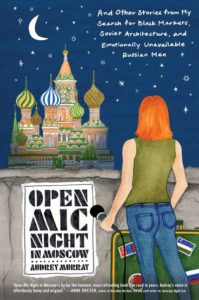

Adapted from Open Mic Night in Moscow: And Other Stories from My Search for Black Markets, Soviet Architecture, and Emotionally Unavailable Russian Men. Copyright © 2017 by Audrey Murray. Reprinted with permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Audrey Murray

Audrey Murray is a redhead from Boston who moved to China and became a standup comedian. The co-founder of the Kung Fu Komedy, Audrey was named the funniest person in Shanghai by City Weekend magazine. Audrey is a staff writer for Reductress.com and a regular contributor at Medium.com; her writing has also appeared in Gothamist, China Economic Review, Nowness, Architizer, and on the wall of her dad’s office. Audrey has appeared on the Lost in America, Listen to This!, and Shanghai Comedy Corner podcasts, on CNN and ICS, and in Shanghai Daily, Time Out, Smart Shanghai, That’s Shanghai, and City Weekend.