Versatile, Universal, and Delicious: Karon Liu on the Magic of Dumplings

"It’s impossible for a dish to remain static, like a museum showpiece, if the people who cook and eat it aren’t static."

I’ve been a Toronto-based food writer for more than a decade, and there’s one project I’ve always wanted to do but never got around to (so far). I’ve wanted to map out this city of almost six million people through dumplings. My map would show the different enclaves and communities based on where all the pierogi places are versus the locations of the wonton soup restaurants or all the manti spots.

Toronto is the perfect city to create such a map: a metropolis that has evolved to be one of the most diverse culinary destinations in the world, thanks to waves of migration resulting in cuisines from disparate parts of the world commingling with each other. This place is a mix of cooks practicing centuries-old techniques learned from previous generations, innovators sharing new creations in the age of TikTok, and cooks embracing their third-culture cooking—combining what they learned from their parents with the new flavors and methods that come from living in a city where a roti spot, a sushi restaurant, and a souvlaki joint can all be found in a single plaza.

A perfect example of this phenomenon is Tibet Kitchen in Little Tibet, a strip of Tibetan-owned restaurants and shops in Toronto’s Parkdale neighborhood. Chaat momos are one of my favorite local dishes: these Tibetan meat dumplings (or veggie, depending on my mood) are smothered in a vibrant orange tamarind sauce, then sprinkled with chopped tomatoes, cilantro, yogurt, and crispy sev, combining Tibetan and Indian flavors; that’s an example of fusion done right—the flavors and textures work so well in every bite.

The more I write about food, the more I come to realize that such an undertaking requires a team of people. Yes, dumplings are universal—it’s why they’re such an easy entryway into a culture’s cuisine. At the same time, there are so many dumpling variations: steamed, fried, or boiled; filled or not; sweet or savory; big or small; in soups or on their own. There are nuances to cuisines that vary between regions, cities, and—heck—households and generations that no one person can ever fully grasp.

Dumplings are universal—it’s why they’re such an easy entryway into a culture’s cuisine.

Technically, the matzo balls in Ashkenazi Jewish cooking, the xiaolongbao or soup dumplings in Shanghainese cuisine, and Jamaican spinners used in soups and stews are all categorized as dumplings. But there’s not a lot else these dishes have in common—aside from their deliciousness. I remember being introduced to spätzle as a teen, when I was invited to a friend’s home to try Austrian home cooking. I gobbled the spätzle along with the schnitzel, perplexed but mind-blown that dumplings existed beyond the wontons I ate growing up.

Heck, even with the wontons, everyone in my friends’ and family’s circles prefers a different filling or fold. One friend prefers the squeeze method—literally putting a bit of filling into the wrapper and then squeezing her hand into a fist to seal it—because that’s the fastest method (and most common among sifus at restaurants). My mom, meanwhile, prefers the fold that makes the dumpling look like a person wearing a bonnet ’cause that’s what her mom taught her. Don’t even get me started on the differences between a wonton, a water dumpling, a potsticker, and a soup dumpling…mostly because I’m still learning the different techniques and regional variations of each of these as I dive ever deeper into Chinese cooking.

*

What I can do is kick-start my hypothetical map with a story about what dumplings mean to me.

For as long as I can remember, when my mom had run out of ideas for dinner and was in a rush, wontons would be one of her go-tos: ground pork, napa cabbage, a mix of dark and light soy sauces with some cane sugar, and a package of store-bought dumpling wrappers. I’d watch her pinch a walnut-sized lump of the filling from a large metal bowl and lay it in the centre of the wrapper. She’d dip a finger into a rice bowl filled with water, swipe the edge of the wrapper, and—through a series of pinches and folds—a dumpling would appear in seconds.

Now a confession: despite all the times I’ve watched my mom make wontons and promised myself that I’d eventually pick up the skill so I could a) have another quick weeknight dinner meal in my arsenal; and b) gain some street cred as a guy who writes a lot about Chinese food, I have yet to tackle making dumplings on my own.

Does not being able to fold a perfectly neat and symmetrical wonton make me any less of an authority on writing about food?

So I consider myself to be in a culinary grey zone. I’m an experienced food writer whose palate gravitates toward Cantonese cooking. And yet I cannot fold a dumpling to save my life. Does not being able to fold a perfectly neat and symmetrical wonton make me any less of an authority on writing about food?

I remember once attending a dumpling-folding party—this is what happens when you have foodie friends. After a few minutes, I was gently, um, encouraged to do something else because I was basically wasting perfectly good wrappers with every failed attempt. Funnily enough, my Hungarian partner, who had never touched a dumpling wrapper before, was able to crank them out without much effort. Since then, he’ll occasionally make a few dozen batches to freeze for future meals. Oddly, the way he folds his dumplings is similar to my mom’s technique. I have no idea if this was a secret joint effort between them to goad me into trying to learn again.

*

In the early months of COVID-19, in January 2020, I went with some friends to a noodle spot in Markham called Wuhan Noodle 1950 to order its dry pot noodles and a side of dumplings. Months before the pandemic emergency was officially declared in Canada, Chinese restaurants had begun to see their business plummet due to old, racist stereotypes about Chinese food and cleanliness, all of which had resurfaced amidst simmering fear about the virus.

This particular place had been inundated with racist prank calls that were perpetuated on social media. Sensing that the eatery could use a positive boost, I went, had a great meal, and wrote about it for the Toronto Star. I explained the restaurant’s regional Chinese cooking and how a place like this fit into the evolution of Chinese food in the Greater Toronto Area.

In recent years, we’ve seen a greater proliferation of regional Chinese cooking from both independent owners and international chains using the GTA as a test market before expanding elsewhere. The Chinese food here evolved from the Canadian-Chinese chop suey houses to more Hong Kong and Cantonese cooking as the GTA saw an influx of immigrants in the eighties and nineties. Then more people from Mainland China came, bringing their regional cooking—as well as international Chinese chains serving everything from hot pot to different styles of noodles.

Chinese food is no longer lumped into one giant category, and diners are increasingly aware that hand-pulled beef noodles are representative of Lanhzou, and in order to get a steamer basket of xiaolongbao, you have to go to a Shanghainese place. While the circumstances of how I found out about this place serving Wuhan dry pot noodles are unfortunate, it gave me an opportunity to talk about the dish stemming from the Hubei province.

Dumplings popped into my life again during the initial months of the pandemic lockdown in Toronto. Bags of frozen potstickers became a bit of a savior in my household in the pre-vaccine days of the pandemic, when every trip to the supermarket seemed like running to get supplies during a zombie apocalypse.

Everyone has a different relationship when it comes to food, including something as seemingly commonplace and traditional as the dumpling.

We bought frozen potstickers in bags of a hundred from a wholesale shop called the Northern Dumpling Co. in our Scarborough neighborhood. During the many days in those early months when I could barely get out of bed, let alone cook a meal from scratch, the dumplings kept me fueled to carry on for another day.

*

Similarly, in the spring of 2022, church basements and restaurants across Canada churned out varenyky by the thousands to raise relief funds for Ukrainian refugees. Diners wanting to show support ordered the dumplings by the dozens and became more interested in learning about Ukraine’s answer to the pierogi.

What I’m trying to say is that everyone has a different relationship when it comes to food, including something as seemingly commonplace and traditional as the dumpling. As people move, generational attitudes and values shift, ingredients and techniques are adapted or evolve, and as technology changes the way we cook, the role food plays in our lives also changes.

It’s impossible for a dish to remain static, like a museum showpiece, if the people who cook and eat it aren’t static. As a result, there will never be a definitive dumpling guide, whether as a map or an anthology, because our relationship to food never stops changing. Instead, consider this volume a snapshot of how our relationship to dumplings stands at this moment, as told by the people in this moment.

Who knows? Maybe, five years from now, if you ask me what my relationship to dumplings is, I’ll be able to say they’re one of my go-to, quick weeknight meals. Perhaps I’ll add masala spice because an Indian restaurant owner gave me a few jars of his dad’s mixes and boasted it could be used in anything. Or I’ll add finely chopped mint to the filling as a nod to the Vietnamese restaurants I always turn to for takeout—and as a way to use local ingredients—because I have a serious overgrown mint problem in my yard.

_____________________________________

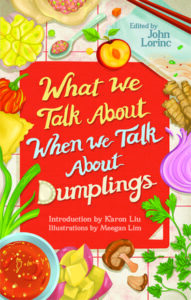

Excerpted from What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings, edited by John Lorinc. Copyright © 2022. Available from Coach House Books.

Karon Liu

Karon Liu is a food reporter with the Toronto Star and was previously the paper's recipe developer and tester. He lives in Toronto and likes to tell people all the good food is in the suburbs. He was also previously the staff food reporter for The Grid, also in Toronto.