Vasily Grossman and the Plight of Soviet Jewish Scientists

The Tragic Tale of the Physicist Lev Shtrum

Victor Shtrum, the protagonist in Vasily Grossman’s novel Life and Fate, did not have to be invented. A Jewish nuclear physicist named Shtrum existed; what is more, he was Grossman’s contemporary and friend.

The fate of Lev Yakovlevich Shtrum (1890–1936) was far more tragic than that of his literary namesake. Shtrum was the head of the Theoretical Physics Department of Kiev (today Kyiv) University. In the early 1920s he formulated the theory of particles traveling faster than light. In 1934 he predicted the existence of 17 isotopes. Two years later, however, during Stalin’s Great Purge, the brilliant scientist was arrested, labelled a “Trotskyist” and “enemy of the people,” and executed. The Stalinist state annihilated him both physically and spiritually: his groundbreaking works in nuclear physics were removed from Soviet libraries and destroyed, and his contributions in the USSR forgotten.

Still, some of Shtrum’s publications have survived in the West and, in 2012, a group of Ukrainian and Russian science historians reconstructed his scholarly biography. Around that time, the physicist Boris Bolotovsky suggested that Lev Shtrum may have served as an inspiration for Grossman’s character.

Grossman first resurrected Shtrum’s name in his novel For a Just Cause, originally titled Stalingrad. It was published in 1952 when Stalin was still alive and would later become the first part of Life and Fate. (This summer, Stalingrad will appear in Robert and Elizabeth Chandler’s translation.) Grossman’s editors never discovered the connection to the executed physicist; they only objected to Shtrum because of his Jewishness. The novel came out during Stalin’s campaign against foreigners and Jews, when Shtrum’s name alone could frighten the editors out of their skin. Despite pressure to eliminate his protagonist, Grossman was adamant: Shtrum would remain in the novel.

Lev Shtrum. Photo courtesy of Elena Shtrum

Lev Shtrum. Photo courtesy of Elena Shtrum

As is apparent from one of Grossman’s surviving letters, he and Lev Shtrum had known each other for years. On February 12th, 1929, a young Grossman, then a student in the Chemistry Department of Moscow University, wrote his father that he saw Shtrum in Kiev and borrowed money from him. At 23, Grossman was hard up and had traveled to Kiev to meet his sweetheart (and future wife), Anna Matsyuk. His casual reference to Shtrum suggests that the physicist was a family friend.

Grossman was trained as a chemical engineer, and his obsession with science is apparent from his early prose. Both Sergei Kravchenko in the novel Stepan Kolchugin and his adolescent protagonist Kolya in the story “Four Days” are child prodigies who devour volumes on theoretical physics, chemistry, acoustics, mathematics, and the natural sciences. Kolya, a Jewish boy, agonizes over his future career, but never doubts that he is destined for greatness: “Should he become a Newton or a Marx?” In Stepan Kolchugin, the half-Jewish aspiring scholar Sergei Kravchenko dreams of advancing his education in Germany or England. Young Grossman himself dreamt of producing synthetic protein and becoming a prominent scientist, even though this would involve circumventing restrictions on education and professions for Jews in the Russian Empire.

Grossman was born in 1905 in Berdichev, which belonged to the Pale of Permanent Jewish Settlement––regions where the Empire’s Jews were compelled to reside. Beginning in 1914 he studied in Kiev––first at a Realschule and later, after the Revolution and civil war, at the Institute for People’s Education. Here Grossman attended Alexander Goldman’s lectures on the fundamentals of physics and chemistry. Goldman played a key role in the development of theoretical physics in Ukraine. He was the founder and first director ofthe Institute of Physics in Kiev where Lev Shtrum first worked as a leading researcher. Decades later, Grossman linked their names in the following passage in Life and Fate, in which Victor Shtrum agonizes over filling out a Soviet questionnaire designed by the NKVD, People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, and meant to entrap:

Surname, name and patronymic . . . Who was he, who was this man filling in a questionnaire at the dead of the night? Shtrum, Viktor Pavlovich? . . . Did he know himself? Perhaps he was someone quite different––Goldman . . .?

Lev Shtrum’s rise as a scientist had inspired Grossman. Born in 1890 into a Jewish family in Ukraine, Shtrum had graduated from a gymnasium with high honors. In 1908, overcoming the three-percent quota for Jewish students, Shtrum entered the Department of Mathematics of Saint-Petersburg University. Shortly before World War I he moved to Kiev, where Grossman’s family also lived at the time. In the early 1920s, after the Bolshevik Revolution and ensuing civil war, Shtrum resumed his career in Kiev, which culminated in his appointment as head of the theoretical physics department at Kiev University in 1932.

Shtrum faced the usual accusations: counter-revolutionary activity, terrorism, plotting to assassinate the member of the Politburo Sergei Kirov, and spying for the Gestapo.Shtrum, a lover of philosophy, also lectured on dialectic materialism, and this brought him in touch with the philosopher Semyon Semkovsky, Lev Trotsky’s cousin. On March 3rd, 1936, Semkovsky was arrested as Trotsky’s relative and executed the following year. Shtrum was arrested by association, three weeks after Semkovsky. Shtrum’s NKVD file reveals that the secret police had kept him under surveillance for over a decade.

Shtrum faced the usual accusations: counter-revolutionary activity, terrorism, plotting to assassinate the member of the Politburo Sergei Kirov, and spying for the Gestapo. During seven months of interrogations Shtrum was tortured, forced to sign self-incriminations, and coerced into testifying against his friend Alexander Goldman. Documents in the recently opened KGB archives in Ukraine show that on October 22nd, 1936, Lev Shtrum, aged 46, was executed with a group of 37 Ukrainian intellectuals, 24 of whom were scientists and professors.

*

For Grossman, Lev Shtrum’s fate exemplified that of a whole generation of Soviet physicists whose careers and lives were destroyed under Stalin. In 1943 Grossman developed an outline for his war epic where Shtrum would become a major character. His elephantine two-volume work took almost 20 years to complete. The first novel, For a Just Cause, covered two initial years of the Nazi invasion into the USSR; the story ended in September 1942 with the first battles for Stalingrad.

Written during “the black years of Soviet Jewry” (1946–53), For a Just Cause was published in the midst of Stalin’s anti-Semitic campaign. Stalin’s campaign against “rootless cosmopolitans,” launched soon after the defeat of Fascism, was accompanied by mass arrests and executions of the Jewish elite. For Grossman this campaign was a vivid reminder of what he had witnessed during the war with the Nazis. In Life and Fate, commenting on the Soviet politics of state nationalism and anti-Semitism, Grossman would remark that Stalin had raised “the very sword of annihilation” over the heads of Jews “he had wrested from the hands of Hitler.”

It took Grossman three years to prevail over his editors and publish For a Just Cause. The novel tells of Victor Shtrum’s mother who, like Grossman’s mother, becomes trapped in a ghetto of a Nazi-occupied Ukrainian town. In Life and Fate Grossman included Anna Shtrum’s farewell letter to her son, written on the eve of the ghetto’s liquidation. From the earlier novel the reader only learns how this letter was carried through the front lines and how deeply it affected Shtrum. By investing Shtrum’s story with autobiographical episodes, Grossman made this character his alter-ego and told the reader of his deepest pain.

On August 2nd, 1949, in the midst of Stalin’s “secret pogrom,” Grossman submitted For a Just Cause to Novy Mir, a literary journal. That same day, realizing he would meet with bureaucratic obstacles, he started a diary to record his novel’s passage to publication. Grossman’s influential editors––first Konstantin Simonov and later Alexander Tvardovsky––were aware that Stalin anticipated a Soviet War and Peace. They were eager to publish an epic war novel, a potential winner of the Stalin Prize. Grossman’s epic had many intentional parallels with Tolstoy’s. Its narrative switched between global events and family occurrences and, like Tolstoy, Grossman depicted historical figures alongside fictional characters.

Victor Shtrum and the Jewish theme quickly became a bone of contention with his editors. The brilliant Jewish scientist was too much for the editor Tvardovsky, who told Grossman, “Well, make your Shtrum the head of a military retail shop.” Grossman retorted, “And what position would you assign to Einstein?” Grossman’s diary reveals that his editors continually pressed him to give up his central character. The writer made compromises and, at his editors’ insistence, included the compulsory content about Stalin and the Party––the price for publishing the novel and saving Shtrum.

As he wrote in his diary in January 1951, “I replied that I agree with everything, except [removing] Shtrum.” In March, he noted that Tvardovsky demanded he “remove all of the Shtrum chapters, every single line—otherwise the novel will not be published.” Grossman rejected this ultimatum. Eventually a compromise was reached when, at Tvardovsky’s urging, Grossman introduced another character into the novel––a Russian physicist Dmitri Chepyzhin, Shtrum’s teacher and friend. This would help downplay the Jewish theme.

Grossman’s novel proceeded to publication at an agonizing pace. Publication was halted several times: Grossman received four sets of proofs. In 1950 Mikhail Bubennov, a member of the editorial board and a participant in the press campaign against “rootless cosmopolitans,” dashed off a denunciation letter about Grossman’s novel to the Central Committee. The proofs were sent to Mikhail Suslov, the head of the Department of Agitation and Propaganda, who oversaw the closure of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC). Grossman drafted 12 different versions of the novel to satisfy the editors’ political demands, but kept Shtrum and much of the Jewish theme.

During Stalin’s campaign “Jewish nationalists” were ferreted out of every profession. From 1948 to 1952 over 100 people, allegedly connected to the JAC case, were arrested and tried. Arrests were conducted even inside the Ministry for State Security (MGB). The ministry’s Jewish personnel, including a senior interrogator in the JAC case, Shvartsman, were purged. By 1952 another list, comprising 200 names, was compiled; Grossman was on this new list.

The publication of Grossman’s novel coincided with the secret trial of the JAC. The trial was launched on May 8th, 1952, the day celebrated worldwide for victory over Nazism; it ended on August 12th with the execution of 13 Jewish defendants. That same summer, in July, For a Just Cause began appearing serially; it was published in four consecutive issues of Novy Mir.

In October 1952 when the last installment of the novel came out Grossman’s editors nominated it for the Stalin Prize. This would help defend the novel from ideological attacks. For a few months For a Just Cause enjoyed positive reviews: critics hailed it as “a Soviet War and Peace” and “an encyclopedia of Soviet life.”

But on January 13th, 1953 Pravda denounced the Jewish doctors, accusing them of conspiring to murder Soviet leaders. Pravda’s announcement signaled a full-scale anti-Semitic campaign across the USSR. National newspapers published articles about “killer doctors.” Grossman’s editors and publishers promptly distanced themselves from the Jewish author. Grossman would later read the verbatim report from one of the public meetings where writers and editors denounced the novel, mainly for its Jewish theme.

Thus, editor and novelist Alexander Chakovsky, although an ethnic Jew, said that the depiction of Hitler “in connection with the Jewish question” was “historically . . . and politically incorrect.” Author Ivan Aramilev compared Grossman to Lion Feuchtwanger, a known “Jewish bourgeois nationalist.” Tvardovsky held a similar meeting at Novy mir, the only meeting Grossman attended, while realizing that the campaign against him could end in his arrest.

During Stalin’s campaign “Jewish nationalists” were ferreted out of every profession. From 1948 to 1952 over 100 people, allegedly connected to the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee case, were arrested and tried.In late January 1953, acting on Stalin’s initiative, Pravda editors drafted an open letter on behalf of the Jewish elite that denounced the Jewish doctors. A list of 57 prominent Soviet Jews was compiled; their signatures were sought. Grossman signed the repulsive letter demanding severe punishment of the “killer doctors.” Ilya Ehrenburg, who resisted and appealed to Stalin, only succeeded in signing a softer version of this same letter. Although the open letter was never published, Grossman did not forgive himself his act of betrayal. He relived the affair in Life and Fate, in a scene where Shtrum signs a similar letter.

In mid-February newspapers launched a coordinated assault on Grossman’s novel. He was accused of writing a “historically inaccurate” depiction of Nazism (implying that annihilation of the Jewish nation was not the Fascists’ main goal), of failing to credit the Party as the organizer of the military victory, and of portraying too many Jewish characters. Stalin’s death on March 5th saved Grossman from being arrested. Attacks on Grossman and his novel continued all through March. But on April 4th the Kremlin publicly disavowed the “Doctors’ Plot.” Things were also beginning to change for Grossman. Several editions of his novel For a Just Cause were soon launched, and in each subsequent edition he restored more of his original text.

*

In 2018, a 95-year-old Elena Lvovna Shtrum, the physicist’s daughter and a former physicist herself, met with Tatiana Dettmer and Robert Chandler in Cologne. Elena Shtrum recalled her meeting with Grossman in the early 1960s. After reading For a Just Cause, she traveled to Moscow hoping to ask the writer about her father. She said she had met Grossman in a publishing house, but they never really got to talk. When Elena Shtrum introduced herself, Grossman appeared frightened and she did not press him with questions.

Grossman’s reaction is understandable. In February 1961 Life and Fate was confiscated by the KGB, and he was placed under surveillance. He avoided political conversations even in his flat, warning his visitors that it was bugged. Acting at risk to himself, Grossman had revived the name of the executed scientist, his friend Shtrum, and managed to keep it secret.

__________________________________

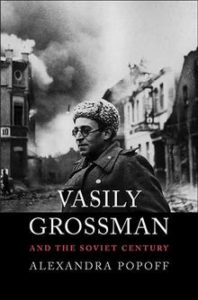

Alexandra Popoff’s Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century is out now.