Unearthing the Stories of Australia's Working Class

Enza Gandolfo on Finding Herself in the Novels of Dorothy Hewitt

I grew up in a working-class suburb of Melbourne, Australia. My parents were Sicilian. They left school at the end of Grade 5. My father worked with his father cultivating land that didn’t belong to them. My mother sewed and embroidered glory box linen for the daughters of the villages’ wealthier families. They barely made enough to live. In the early 1950s, they left Sicily in the hope of making a better life. In Australia, my father worked in a foundry, double shifts whenever he could get them. My mother worked in various textile factories, then later as an outworker (in the backroom of our house), usually on a “piece work” basis.

Most literary novels are about the middle class, so much so that we don’t often think about class when we read them. Being middle class—like being white and male—is read as the universal human experience. There were no people like me or my family in the novels I read as a child. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, this exacerbated my feelings of inferiority and marginality. There was a sense that to obtain the life my parents wanted for me I had to leave them and my class behind.

When I was 11 I read my first working-class novel, A Bunch of Ratbags by William Dick. This novel was about a young boy who lived in my neighborhood. As an adolescent I read other working class novels, but they were few and far between—John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, Charles Dicken’s Hard Times, D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers. However, it was a novel by the Australian writer Dorothy Hewitt, Bobbin Up (1959), which I read in my late teens that made a lasting impression.

The novel is set in Sydney in the late 1950s and tells the story of several women working in the Jumbuck spinning mills. The women are underpaid and overworked. Hewitt was not working class herself. She came from a rich rural family but she was a Marxist and a member of the Communist Party. In the late 1940s she took a job in a Sydney spinning mill because she wanted to help the working class, a move that might appear patronizing and naive now, but an experience that inspired Bobbin Up. The novel focused on working women’s lives, not only their lives at work but their relationships with lovers, family, and other male members of the left who were often dismissive of the women and their rights. It was the first novel I read about working class women. It was political and poetic and women were at its center.

The representation of the working class in popular media is often either romanticized—the noble, voiceless, tough-as-nail, salt-of-the-earth men and women—or it plays on the opposite stereotypes—lazy, bigoted and uneducated crims. Often when books with working-class characters are published, they are works that perpetuate these ideas: misery memoirs that highlight abuse and poverty, novels that trace the heroic climb from working-class boy to middle-class man, and stories of the struggles of the working-class “minions” bound to blindly follow orders.

Dorothy Hewitt’s Bobbin Up did none of those things. She wrote about real women who were struggling against sexism and a capitalist system that discriminated against workers, but also living their lives. They were sexual, they were political, and they were mothers, wives and daughters. As I began writing in the early 90s, I was also inspired by the novels of Toni Morrison, in particular Beloved, Jeannette Winterson’s Oranges are the Only Fruit, and Rosa Cappiello’s O Lucky Country. These novels expanded my understanding of the complex nature of identity and of the impact of those complexities in people’s lives.

*

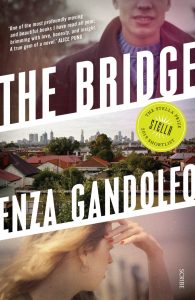

On October 15, 1970, in one of the worst industrial accidents in Australia’s history, a span of the West Gate Bridge in Melbourne collapsed during construction. More than 60 men were working on the site that day and 35 were killed. This tragedy inspired my novel, The Bridge. I was 13 years old when it happened. I remember standing in the school quadrangle with my friends, surrounded by the screech of the sirens as emergency vehicles raced to the site. The principal called to the office all students with relatives working on the bridge. We fell silent. Among us were the children of men who had died or been injured in previous accidents. We all knew the consequences of these tragedies. When the Royal Commission finished its investigations nine months later it was clear that the collapse of the West Gate Bridge was due to the negligence of the companies involved in the construction and design: “Error begat error … and the events which led to the disaster moved with the inevitability of a Greek Tragedy.”

When I was writing The Bridge, I knew that my characters did not need to exist in relation to the middle class.

In my novel, the protagonist Antonello is a 22-year-old rigger who has been working on the West Gate Bridge for almost two years. When the bridge collapses, Antonello survives but two of his closest friends die. The first half of the novel traces Antonello’s story up until a few days after the collapse. The second part is set in 2009 and begins with Jo, a 19-year-old working-class woman who has too much to drink one night and gets into a car accident. Her best friend is killed. The rest of the novel traces the impact of this second accident on both Jo and Antonello.

To step into these characters’ shoes, especially those of the working-class men who worked on the bridge in the 1970s, I had to understand the nature of their daily lives, not only their work but their relationships and communities. There were several key lessons I learnt during the writing of this novel: the value of research (archival and oral), the importance of challenging the clichés and tropes associated with class and of taking into account the impact of intersecting identities—especially race, gender, ethnicity, the need to understand the era (including key events, attitudes and cultural mores), and the power of situating the working class as central and not in the margins of the middle classes.

Characters exist in time and in place. Being aware of what is happening during the era you are writing about is crucial.

Dorothy Hewitt spent nine years in working class jobs, this proved invaluable in understanding the women working in the spinning mills. While I couldn’t go to work on a bridge, I did do substantial research. I read the articles in newspapers that told the stories of the men who died and of the survivors. I read the statements by the 50 plus witnesses called by the Royal Commission and I talked to many working-class people who lived near the bridge in the 1970s. We know working class men and women are often exploited, that bosses want them to do more for less. But the experience of work isn’t the same for everyone. While some working class jobs are boring and repetitive, this is not always the case. During my research, I learned how much the men loved working on the bridge. “When you are in construction you build lots of buildings,” one survivor told me, “but you only ever get to build one bridge.” I learned how proud they were of their work and the contribution they were making to the city and the city’s future.

I also came to understand the importance of unionism to the men in a way I hadn’t understood before even though I had always belonged to a union. They were doing dangerous work, they knew this—they had to depend on each other and on the collective in a way that those of us who work in white-collar jobs never have to. However, the men on the bridge were not just poor workers whose identities are defined by struggle. Like all of us, they had dreams and aspirations, they had relationships and families, and all of these aspects of their lives are important to the story. They were sons, fathers, husbands, and friends. When I was writing about Antonello, I knew that he was in love, newly married, and had plans for the future, the tragedy impacted on all of those aspects of his life not just his work.

Dorothy Hewitt, Toni Morrison, Jeannette Winterson, Rosa Cappiello and others taught me that the experience of being working class is different depending on a person’s gender, race and sexuality and highlighted the importance of taking note of the way these social identities intersect and impact on people’s lives. Characters exist in time and in place. Being aware of what is happening during the era you are writing about is crucial. In the 1970s, the young men working on the West Gate were worried about being conscripted and sent to Vietnam, many of them were migrants from southern Europe and faced prejudice based on their ethnicity, and no women were working on the bridge because women were still expected to stay home when they had children.

When I was writing The Bridge, I knew that my characters did not need to exist in relation to the middle class. I remembered Australian journalist Jana Wendt interview with Toni Morrison in the 1990s:

Wendt: You don’t think you will ever change and write books that incorporate white lives into them substantially?

Morrison: I have done.

Wendt: Substantially?

Morrison: You can’t understand how powerfully racist that question is, can you? Because you would never ask a white author, “When are you going to write about black people?”

It was a racist question. For me, listening to that interview reinforced the dominance of not just white, but also male and middle class narratives, and the assumption that the rest of us and our stories belong in the margins. A city, a country can’t function without the working class, without those people who build our roads, collect our garbage, keep our rails functional, clean our office buildings. These people have stories too, stories worth telling, stories we need to tell if we are going to understand who we are as a people, as a nation, as human beings living in a society, with all its connections and interconnections.

__________________________________

The Bridge is available now via Scribe Publications.

Enza Gandolfo

Enza Gandolfo is a Melbourne writer and an honorary professor in creative writing at Victoria University. She is interested in the power of stories to create understanding and empathy, with a particular focus on feminist and political fiction. The co-editor of the journal TEXT and a founding member of the Victoria University Feminist Research Network, her first novel, Swimming (2009), was shortlisted for the Barbara Jefferis Award.