Ulysses: A History in Covers

The Many Lives of a High-Modern Classic

Ulysses, in its 93 years on this earth, has gone from controversial to canonical, from depravity manifest to touchstone of sophistication. What Virginia Woolf once decried as the “illiterate, underbred book… of a self-taught working man” is now regarded as the exemplar of high modernism. In the process of arriving at this lofty cultural position, Ulysses has endured many slights, inhabited many forms, and worn many, many covers. An overview follows:

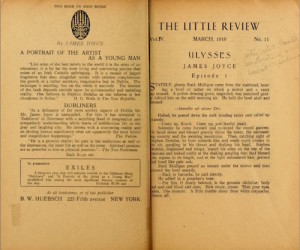

The Little Review, 1918-1920

Ulysses was first published between 1918 and 1920 in serial form by The Little Review, an American literary magazine. Despite a lengthy endorsement avowing Joyce’s artistic value penned by H.G. Wells, it so deeply offended the American public that its publishers were arrested for obscenity. All copies of the Review were removed from circulation, fines were incurred, and Ulysses was banned in the United States for the next 14 years.

Shakespeare and Company, 1922

Ulysses was given second life by Shakespeare and Company after a distraught Joyce appealed to Sylvia Beach. A champion of Joyce’s work, Beach detested “the spectacle of ignorant men solemnly deciding whether the work of some great writer is suitable for the public to read or not” and worked to have 1,000 copies of the manuscript published in Paris. Although she was nearly bankrupted by the process, she both believed in Ulysses’ artistic merit and in the success its notoriety would bring to her business.

Odyssey Press, 1933

While bookstores in America were still being persecuted for illegally selling the Shakespeare edition, Beach had the German Albatross Press take over the book’s European publishing; they established an imprint called the Odyssey Press for this purpose. To avoid legal problems, they inscribed this editon’s back page with a note reading, “Not to be introduced into the British Empire or the U.S.A.” This is considered to be the most accurate representation of Joyce’s authorial intent and contains corrections by Stuart Gilbert, who had claimed the title of “the official Joycean.”

Random House, 1934

In 1933, Random House received the rights to publish Ulysses in America and subsequently contested its illegality. Presiding Judge John M. Woolsey overturned the ban and praised Ulysses for its literary value, stating that “Joyce has attempted… with astonishing success to show how the screen of consciousness with its ever-shifting kaleidoscopic impressions carries, as it were on a plastic palimpsest, not only what is in the focus of each man’s observation of the actual things abut him, but also in a penumbral zone residua of past impressions, some recent and some drawn up by association from the domain of the subconscious.”

Joyce received a $45,000 advance which, according to the letters of Janet Flanner, “he failed to announce to [Sylvia Beach] and of which… he never even offered her a penny.” The edition was designed by Ernst Reichl, a typographer and graphic designer who designed more than 2,000 books for such literary luminaries as Gertrude Stein, Joyce Carol Oates, and Kurt Vonnegut.

Henri Matisse Illustrated Edition, 1935

The American publisher George Macey offered Henri Matisse $5,000 to create accompanying illustrations for a special edition of Ulysses. Matisse chose six figures from Homer’s Odyssey and created six soft-ground etchings, as well as 20 lithographic drawings made as studies for the etchings. 1,500 editions were printed, 250 of which were signed by both Joyce and Matisse.

The Bodley Head, 1936

A thousand copies, designed by Eric Gill, were published of the first English edition of Ulysses. Joyce expressed disappointment in the printing, in which he found “an incomprehensible amount of errors.” After the initial published versions of the book were sold, The Bodley Head released an inexpensive trade copy of the book including many of Joyce’s corrections that was reissued several times.

Random House, 1946

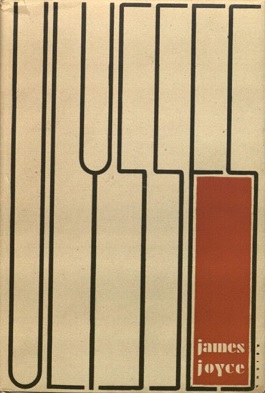

Vintage Press, 1961

The first U.S. paperback edition to be released.

Gabler Edition, 1984

Professor Hans Walter Gabler, a James Joyce scholar, formed a committee in order to resolve the several hundred to five thousand errors present in any given edition of Ulysses. Deciding that all previous editions were corrupt, Gabler endeavored to reconstruct the text using Joyce’s original, often handwritten, copies. Although he was “breaking new ground” through his use of computers to complete the manuscript, several experts found his methodology to be deeply unsound. This great controversy created a schism that has left Joyce scholars divided to this day.

Penguin Books, 1986

Lilliput Press, 1997

This edition “liberates the text…and makes it possible for the first time for the general reader to relish every nuance and beauty of Joyce’s masterpiece,” at least according to its marketing sheet. Rejected by both scholars and Joyce descendants, it was discontinued after The Joyce Estate successfully sued editor Danis Rose for copyright infringement. Only 900 copies of the original 1,000 remain.

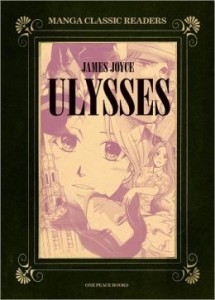

One Peace Books, 2012

One Peace Books reprinted several classic 20th-century novels reimagined as Japanese manga. The text has been animated, significantly shortened, and comically paraphrased. Keeping Joyce’s name on the cover is perhaps inaccurate and probably would have offended him, given the enormous volume of corrections he made in published versions of the novel throughout his lifetime. Unfortunately for Joyce and the estate that formerly controlled the original manuscript, the copyright for Joyce’s novels expired in 2011, releasing all texts into the public domain. Revising Joyce’s erudite prose and wandering sentences does make it a much more readable—and therefore unrecognizable—edition.