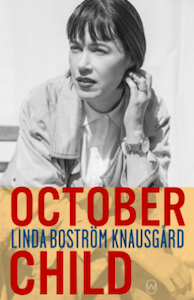

Trust the Text: On Translating the Autobiographical Novel of Linda Boström Knausgård

Saskia Vogel Considers the Role of Writing as Memory in October Child

“I wish I could tell you all about the factory, but I can’t anymore. And soon I’ll no longer be able to remember my days or nights or why I was born. This is what I know: I was there for several long stretches between 2013 and 2017 and my brain was shot through with so much electricity that they were sure I wouldn’t be able to write this.”

*Article continues after advertisement

So begins Linda Boström Knausgård’s October Child, the author’s account of her periodic stays in a Swedish psychiatric ward, which she refers to as “the factory.” There, she was subjected to electroconvulsive therapy “treatments” (their word) that robbed her of her memories. The treatment, the author was told, would be comparable to restarting a computer, but to her it is “like drinking darkness.” She writes that soon she’ll no longer be able to remember her days or nights or why she was born.

Each time I read this, I think of what eludes us all and what is forever slipping away. I am reminded of an experience I have each time I start a new translation project—my translation of October Child is no exception. As I make my start, I am visited by the thought that I won’t be able to translate this, and towards the end, another thought: I could have translated everything differently.

In Knausgård’s autobiographical novel, the bounds of fantasy and reality become porous—time is not linear, beats are skipped. Emotional highs and lows, a “genetic predisposition to delusions of grandeur,” and self-effacement follow each other in a breath. The effect is exhilarating. As I started to unpack the notion of not being able to translate the book, I realized it was in part because I was still relating to the book as a reader. I hadn’t yet settled into the voice and tone, my generative role. My intuition hadn’t kicked in.

But even after I started working, something didn’t feel right. I couldn’t stop thinking about what it means to trust my intuition, which also comes up as part of Knausgård’s discussion of memory.

Memory, its purpose and value, is a central theme in October Child. To the narrator, her memory loss is devastating. However, caring about her memories does not seem to be part of her program of care. The results-focused doctors in October Child are cavalier about the impact of the treatment’s side effect on the narrator:

Nobody cared that I wouldn’t be able to remember large swathes of time afterwards. […] Memories had a low status in the factory. They’d rather give you four weeks of voltage than have you wobbling around the ward for months on end.

At one point, a doctor pronounces the treatments a success. But success by which measure? The only difference Knausgård notices is the memory loss. She wonders if this might well be the point: “Maybe they have to keep going until I can’t remember any of their names or actions. I’ll forget my name and where I’ve been. I’ll forget the factory.”

Memory, its purpose and value, is a central theme in October Child.

The first-person narrator confronts this doctor: “I said I was an author and that I needed my memories.” Only then does he look up from her file and, adding insult to injury, tells her that

[…] the memories would come back. They always do. Sooner or later. Perhaps not all of them, definitely not all of them, but it’s hard, if not impossible, to find a treatment that’s free of side effects. You understand, don’t you? You can always make things up. Isn’t that what authors do?

Knausgård physically attacks him, a reasonable response to this cruelty and carelessness.

The treatment that is supposedly a success disrupts a fundamental security: the sense of the integrity of one’s mind. The treatment alters this relationship of trust between the narrator and her mind—or suspends it temporarily, as the doctor seems to believe, thinking nothing of the devastating collateral damage that the author must learn to live with. Even if all her memories did return, how would she know? How would anyone know?

*

Each time I sit down to translate, I think about what the book holds, and then resign myself to the fact that whatever my approach, however thorough I am, something will go missing: something Swedish can do but English cannot and vice versa, a reference, a turn of phrase, some nuance, something the author placed between the lines. I think of what I have added to my own writing just for me. Perhaps it’s the word I chose because of what it means to me in the moment; a choice important to me, but nothing I’d expect to resonate in the same way for anyone else, much less in translation. I also know that I might forget that it is there in the future, when memory fades.

I read October Child as a book in which the author is becoming reacquainted with her mind and seeing what unfolds when she spends time in the space of memory. And though it is made clear that her memory has been compromised, the reader is reminded that her relationship to writing itself is intact; it’s something she always has at her disposal. She writes, “I knew it deep down, even in the years I wasn’t writing: All I would have to do was sit down and the words would come.” The only thing better than writing, she writes, is “[g]alloping [on horseback] with open rein through the forest.” Like riding, writing is an intuitive act.

Writing also seems independent of memory, or perhaps beyond it, from a place in the mind and body accessible only in the act of writing, an altered state, as in this passage:

After a year and a half on the island I’d finished my first book. It was as though I’d written it in my sleep, and this truly frightened me because it didn’t feel as if I knew what I was doing when I was writing. This feeling has never left me, though perhaps I have grown somewhat used to it.

As though I’d written it in my sleep, it didn’t feel as if I knew what I was doing. Frightening, perhaps, but this state also describes a person perfectly in tune with their instrument, not thinking, just doing. Sublime. She describes the writing process: “I follow the flow of words and nothing goes wrong. If it does, I sense it right away.” All intuition.

I yearn for this state in writing as well as translation. But as I approached this translation, I started thinking of caveats, reasons why I shouldn’t trust my intuition. I was staring at my instrument, stunned by the fact that I am able to play it at all, paralyzed by the number of decisions I make when I am in the flow.

What came to mind? For a start, I consider the elements of style I continue to find in contemporary Swedish prose that can require a different treatment in English: brief exchanges of dialogue that can become too terse if transposed directly, losing depth; a greater tolerance for localized repetition, very short or fragmented sentences; a different relationship to past and present continuous verb tenses in which a certain backdrop for the action is set up alongside the verb, which might go some way to explain why “body acting” in prose is more common: the difference between “I sit and write this essay” and “I am writing this essay;” the rhetorical strategies that leave the reader to make connections, where in English I was taught by writing workshops and editors that one should probably add a transition. But should I? Which of these elements of style do I retain?

Each book, each language, calls for a different approach.

Beyond my sense of my languages is the cumulative effect of the feedback and discussion of writing in general and the work I do in particular: As I approach this translation, which queries have I learned to anticipate from an editor, and should I make edits now based on those imagined queries? Are those queries even legitimate? (How did the localized repetition of care/caring towards the start of this essay sit with you? It was queried by the editor.)

Each book, each language, calls for a different approach.

Between Swedish and English, one can, to an extent, map the source text onto the target language and end up with a fairly fluent translation. As a result, my first drafts are often quite literal, and I spend a lot of time considering how far I can stretch the boundaries of English. How much can this English rendition stretch before I lose the connection with the reader? But who is this reader for whom I’m translating?

*

The questions just kept coming. I looked forward to the author’s guidance. I kept a list of questions—what is the feeling behind this image? The translation of this word could skew positive negative or neutral in English, which nuance do you prefer? And so on. I can see now that I was yearning for the concrete, for certainty. Take this passage as an example:

This day tastes of iron. We know we are alone. The children come, one by one. Nothing bad should ever be allowed to happen to them. Their hands out in the sky. We were plucking the stars. Washing dishes. We ate of each other. Our dreams mourned their origin. We forgot in order to make space. Were we afraid of death? Yes, but we were more afraid of life.

Reading this now, I wonder why I didn’t translate this as follows: “Their hands out in the sky. We plucked the stars. Washed dishes.” That would be closer to the Swedish. But I think of the past continuous tense. I must have read the fragment “their hands out in the sky” as the backdrop for the action: plucking, washing. When I read this sentence and two fragments in Swedish, my intuition tells me that hands unfolds into plucking and then into washing. Something abstract becomes an action becomes a memory. I don’t feel the same effect with plucked and washed. Then the verb tense shifts in English, which in my mind gives the sentences that follow the space they need to unfold.

This decision-making process is repeated innumerable times in any translation. My problem here was that I was staring at the book, my document, the keyboard, second guessing everything. A dangerous proposition that is and is not part of the job. Dangerous because it leads to a territory that feels taboo for a translator to admit, grounds for dismissal from our guild because it threatens the trust I believe an author needs to feel for their translator so they can be sure their work is in good hands. Though I believe that there must be room to falter, whatever the craft or art. I think of the happy accident, but also the way muscle memory is built through repetition. When I mis-type a word, I still delete it and type it again just to train my hands. What was all this questioning for? It seemed only to be clouding my intuition.

When the author’s reply came, one particular comment became a lodestone. Trust the text, she wrote. Yes, in this translation all my questioning and interpreting was doing a disservice. So in the next draft, I stopped staring at my instrument. I saw what was clouded before. I let go. I followed the variations in tone, the highs, the lows, held in mind images as they lingered, did not try to resolve what wavered, but took it in, let it be. And if I felt myself faltering, I reminded myself to trust what was there. It became a different book entirely.

__________________________________

October Child is available from World Editions. Translated by Saskia Vogel. Copyright © 2021 by Linda Boström Knausgård.

Saskia Vogel

Saskia Vogel is a writer and Swedish-to-English literary translator from Los Angeles. Her debut novel Permission (Coach House Books, 2019), a story of love, loss and sacred sexuality, was published in five languages. She is a PEN Translation Award finalist and was awarded the Berlin Senat grant for non-German-language literature in 2021.