There were two basic types of alcoholics, Elfrida realised, and she liked to categorise them as “Sippers” and “Benders.” “Benders” were out of control—wholly appetite-driven, consummation was rapid and destructive, swift oblivion was the aim. Days would go by when “Benders” were on their bender—lost weekends—that usually ended with collapse, catatonia or death. “Sippers” on the other hand were more discreet and shrewd. They steadily topped themselves up throughout the ay—sipping—aiming to maintain a constant level of potent, satisfying but—hopefully—unnoticeable inebriation. Unlike Benders, Sippers—while effectively very drunk—could still function, conduct a conversation and maybe even hold down a job.

Elfrida poured some vodka into her breakfast orange juice. She wasn’t deluded or in any form of denial, not at all: she knew she was an alcoholic of the “Sipper” variety, and she also knew that the day that she started writing a new novel she would be sober again. That was her particular problem: creative impasse had driven her to drink. It wasn’t her fault or some flaw in her character, no. Many other writers and artists had experienced the same predicament—Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, poor Edith Everly, Faulkner, Elizabeth Bishop, Dylan Thomas, Morris Hughes, Brendan Behan, Henry Green, sad Malcolm Lowry, Celia Tanson, Evelyn Waugh, Ian Fleming, George Vanderpoel and a good few others whose names she couldn’t currently recall. It was a small exclusive club. Actually, not that small, come to think of it. Pondering her list she realised that most of them were “Benders.” Odd, that.

Yes, she thought, feeling pleased with herself, matters were being brought in hand, steps were being taken, light was spottable at the tunnel’s end, and so forth. She added another dash of vodka to her juice and went to find the telephone number of the Book Nook.

“Hello, I’d like to speak to Huckleberry, please.”

“Huckleberry here.”

“Huckleberry, good morning. It’s Jennifer Tipton on the line.”

Elfrida poured some vodka into her breakfast orange juice. She wasn’t deluded or in any form of denial, not at all.

“Sorry? Who?”

“You ordered Virginia Woolf’s A Writer’s Diary for me.”

“Did I? Morning.”

“And you sold me a copy of Maitland Bole’s book. Or, rather, pamphlet.”

“It’s all coming back to me, Miss Tipton.”

“Mrs.”

“Mrs. Tipton. What can I do for you?”

She explained that she was telephoning for Maitland Bole’s number, or address, if that were possible. She wanted to congratulate him on his pamphlet— it had been exceptionally useful in her researches into Virginia Woolf.

“I don’t think I can really do that,” Huckleberry said.

“Why not? You told me he lived in Eastbourne.”

“He’s a very private man, you see. I can’t just give out his number. He’d be furious.”

Elfrida had a moment of inspiration.

“Well,” she said, “would you convey to him the information that I’d like to buy fifty copies of his pamphlet? Do give him my telephone number. I won’t be furious.”

“Oh. Right. I’ll see if I can track him down.”

Maitland Bole himself telephoned ten minutes later. He had a rattling voice, much interrupted by throat clearings and dry staccato coughs. It turned out that Bole no longer lived in Eastbourne but in London, in Fitzrovia, he volunteered, vaguely.

“Could we meet?” Elfrida asked. “I’ve got some questions for you, seeing as you’re such an expert on Virginia— and I could give you a cheque for the pamphlets at the same time.”

Bole suggested that they rendezvous at midday the next day at the main entrance to the Tate Gallery on Millbank. He had “private business” to transact there, he confided.

“Perfect. And may I take you for lunch?” Elfrida invited. “The Tate restaurant is one of my favourite places.”

After a fusillade of coughs, Bole agreed.

“How will I know you?” he asked.

She thought for a second: how to describe herself? Tall, with thick dark hair cut in a heavy fringe, red lipstick? Hardly a stand-out in a crowd.

“I’ll be carrying a copy of To the Lighthouse. How about that?”

“See you tomorrow, Mrs. Tipton.”

She thought for a second: how to describe herself?

Elfrida replaced the receiver on its cradle. Her heart was bumping as if she’d run up three flights of stairs. She was sure her life was about to change— and the wine list at the Tate restaurant was one of London’s finest. She would woo Maitland Bole with the very best claret and extract the secrets of Virginia Woolf ’s last day from him.

She went upstairs and packed an overnight bag. She wasn’t going to wait any longer—she’d catch a train up to London right away. And she had other business in the city. The morning’s mail had brought enthusiastic letters from agent and editor, both “dying” to hear more about The Zigzag Man. She felt her fortunes were on the turn.

She wrote a note for Reggie—“Gone to London on business. Call me at home. Back next week. E.”—and she telephoned for a taxi to take her to the station. Reggie would be happy—a whole weekend to fuck whatever tart he was fucking and no wife in view. Bliss.

__________________________________

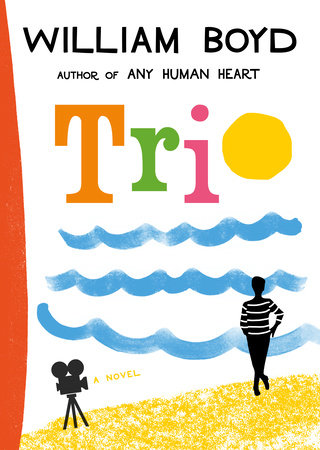

Excerpted from Trio. Copyright © 2021 by William Boyd. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher.