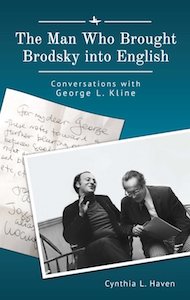

George L. Kline translated more of Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky’s poems than any other single person, with the exception of Brodsky himself. He described himself to me as “Brodsky’s first serious translator.” Bryn Mawr’s Milton C. Nahm Professor of Philosophy was a modest and retiring man, but on occasion he could be as forthright and adamant as Brodsky himself. In a 1994 letter, the Slavic scholar wrote: “Akhmatova discovered Brodsky for Russia, but I discovered him for the West.” And in 1987, “I was the first in the West to recognize him as a major poet, and the first to translate his work in extenso.” It was all true. He was, moreover, one of the few translators who was a fluent Russian speaker.

Brodsky’s first book in America, 1973’s Joseph Brodsky: Selected Poems, changed my life as well as the poet’s—and all the translations were Kline’s. The meditative poems of time, consciousness, suffering, alienation, even redemption sounded a note that was octaves above the free-form narcissism, the weary story of the self that typified American poetry at the time. This book established a Western audience for Brodsky, and blew open a window to the East. I studied with him at the University of Michigan, and that was a formative experience, too, as it was for so many of his protégées who became writers in his wake.

This is the story of how that book was born, and what happened in the years following. The three-decade collaboration of Kline and Brodsky is a tale that has not been told in its entirety until now.

The first translation one reads of a foreign poet makes an indelible impression, and so I confess a bias, since Kline’s translations were the first that I read. But my preference wasn’t wholly subjective; and I wasn’t alone—they made an impression on the entire Anglophone world. They also launched a stunning, unconventional literary career in the West for Brodsky.

In the years since, his translations have sometimes been disparaged, often for the occasional infelicity, though few translations lack them. (Kline was considering a new edition of the Selected at the end of his life, which would have included his corrections and newer translations. It never happened.) More often they were simply overlooked as more famous poets and translators took on the task.

He was obviously not a superstar poet—such as Richard Wilbur, or Seamus Heaney, or Anthony Hecht, who also translated Brodsky’s poetry although they didn’t know Russian—but rather a Slavic scholar with a serious interest in poetry. This book shows how deep this philosopher’s commitment was, and that these poems were not the whimsy of a dilettante. His translations were important not only because they were the first, but because they tried to preserve, as Brodsky wished, the metrical and rhyme schemes of the original, often with surprising sensitivity and success.

As I pored over the book with the stylized green-and-purple portrait on the cover as a university student, I knew nothing of the translator, George L. Kline. Yet the book, the man, and the poet would be one of the more remarkable adventures of my life. The three of us formed an unlikely troika of temperaments and training, friendship and estrangements.

George was meticulous, reserved, and deeply principled; Brodsky was an evident genius, a Catherine wheel of a man, who fraternized with the leading cultural figures of his time. The two were lucky to have found each other; yet their personalities were worlds apart. I entered the scene writing about both men decades later, undoubtedly one of the girls described in Brodsky’s 1972 poem “In the Lake District,” the place where he had been appointed “to wear out the patience of the ingenuous local youth.”

Though we had never met face to face, George would become a regular presence in my life. The connection began after my publication of 2003’s Joseph Brodsky: Conversations, my carte d’entrée to the world of Brodsky scholarship. After the book was out, I received a multi-page letter with “corrigenda.” I later learned that anyone in the world who wrote or published something about Joseph Brodsky could expect such a patient, careful list of corrections. He was thorough, neutral, scholarly—welcoming and encouraging, too.

According to his colleague Philip Grier, writing in the Slavic Review, “George Kline was an exceptional exemplar of humanitas: kindness, culture, refinement.” Brodsky scholar Zakhar Ishov told me that Kline “was a decent man,” and not in the bland and neutered sense of the term, but in the sense of an endangered species.

Wherever we are, at whatever stage of our journey, those who work with Brodsky’s corpus owe him a great debt. So do translators more generally. He encouraged every scholar and translator, no matter how new and ill-equipped for the job at hand. When he was invited to judge the Compass Translation Competition, held under the auspices of the Cardinal Points Journal, his letter to Russian poet and translator Irina Mashinski signaled his magnanimity and sense of fairness. On January 21, 2012, he wrote to her:

As you may know, in the past, film awards (both Golden Globes and Oscars) were announced with the formula ‘And the winner is…’ However, in recent years, for good reason, this has been changed to ‘And the Golden Globe [or Oscar] goes to…’ The Russian pobeditel′ that you used last year is even stronger than ‘winner’; to me it suggests that those who didn’t get the prize were not only ‘losers’ but ‘defeated ones.’ Why not say simply ‘Congratulations on the selection of your translation’? And to the others ‘We regret that your translation was not chosen’? Both of these formulas would soften the harsh image of competitiveness that is implied by the language of ‘winners’ and ‘losers.’

The Man Who Brought Brodsky Into English: Conversations with George Kline is a tribute and a gift from all of us, winners, losers, and the rest of us.

As the years went by, I would occasionally phone George Kline at Christmas. Every year I would get his detailed family holiday letter. It touched lightly on George’s professional work, including instead family news, recent travels, and health updates for his family, especially his beloved wife Ginny and “Bunny,” the Klines’ disabled daughter. For news of his scholarly labor (he was revising this or that essay, publishing a new study), I would have to follow up by phone to Anderson, South Carolina, where he had retired.

In 2012, I made the seasonal call. We hadn’t talked for a while, so we updated each other on our articles and books. After a short conversation, he abruptly announced the end of our chat with unexpected firmness: “I’ve got to go.”

“Sure, George. But why?”

“We’ve been talking for 12 minutes.”

“Yes. So?”

Then he said with slow emphasis: “I am 92, you know.”

No. I didn’t know. How would I? We had never met. I couldn’t even recall seeing a photo of George. I knew he was getting on, but I didn’t have a mental picture of this nonagenarian who was, actually, a few months shy of his 92nd birthday.

I had always meant to gather his memories. But at that point in my life I had just embarked on the book that became Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, a biography of the French theorist and personal friend. I had also just launched an innovative communications program at Stanford. However, I knew it would be foolhardy to postpone any longer. Not only for my sake, but for the benefit of scholars around the world who had been guided by his tutelage, improved by his impeccable corrections and guidance, and inspired by his meticulous standards.

We began our work together in January 2013. I was interviewing a man in failing health, who was only capable of conversations of up to 20 minutes in the morning, while he was still fresh. (Some days he couldn’t talk at all, and on one banner morning we talked for about 40 minutes.) We couldn’t wait for a better time. With characteristic stoicism, he was adapting to the possible, not pining for the ideal. We both sensed it would be the only opportunity.

Over the subsequent months, our interviews filled hundreds of pages. The work was “exhilarating, but often challenging and exhausting,” he wrote in a letter to Ishov. Much of our conversation was repetitious, chit-chat about peripheral people or events, discussions of his health or arranging the next telephone rendezvous, but over the months, I would learn of his courage and his sense of honor, as well as the precision of his scholarship.

The three-decade collaboration of Kline and Brodsky is a tale that has not been told in its entirety until now.

In the Brodsky world of intellectual brilliance and acrobatic language, George’s conversations, occasionally punctuated with stiff little jokes that ended with flat punchlines (he’d sometimes repeat them to drive the point home), would seem to make him the odd man out. He was there, he would say, because he didn’t have “a poet’s ego,” and he could work from the original Russian, and did not attempt to impose his own forms on the formal cadences, rhymes and slant rhymes, and complicated metrical structures of the original. I also learned of his patience and his peevishness. I began to sense in this staid Unitarian a profound religiosity beneath the surface, and that he shared with the poet a sacred vision of the world. And I came to know his wounded pride.

In our conversations, he described his meeting with the poet who would change his life, his run-ins with the notorious KGB, and other untold or little-known details of his friendship with Brodsky. He spoke about the poet’s generosity in 1974, when he was “disinvited” from giving a reading at Italy’s Spoleto Festival because of Soviet blackmail. Or the “White Nights” in June 1968, when Brodsky rented a rowboat and took Kline down the Fontanka in the early hours of the morning. Or in October 1987, when Brodsky’s Nobel Prize was announced, and Kline phoned him in London to say “Congratulations, Joseph!” Brodsky responded, “And congratulations to you, too, George!”

I also learned more fully about his heroism, a subject we touched on in our interviews, though his modesty deterred him from giving a full account of his bravery. During World War II, as a navigator and bombardier in B-24s, he flew 50 important combat missions out of Italy, for which he received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

He described how, as Brodsky insisted more and more on his own translations, he eventually seemed to leave the Russian scholar behind, favoring the work of other translators and, Kline thought, dismissing him as intractable. He had, to some extent, anticipated this. Even before Brodsky’s arrival in the United States, the scholar had written in a letter, “I’m not a possessive translator, and I’m convinced that others some day will translate Brodsky more successfully than I’ve been able to do. I welcome pluralism in the Englishing of any foreign poet.” Although Kline felt slighted, the friendship continued till the end, as did their work together. Kline attended his final birthday party months before the poet’s death.

As we persevered, a more ambitious goal developed. We began to hope these conversations would be edited and pruned into a book to complete the oral history of Joseph Brodsky, so comprehensively undertaken by Valentina Polukhina in Brodsky through the Eyes of His Contemporaries. George Kline was one of the few major figures in Brodsky’s life who had not been interviewed for the volumes.

We were running out of time. The phone calls—punctuated by constant sips of water to keep him going; sometimes he was breathing audibly—gradually yielded to longer breaks in the conversation to check on the well-being of his beloved wife or daughter. As his energy was fading, he was urging me to use his earlier articles to augment our interviews, since our conversations were missing strategic parts of the story.

But the future was vaporizing. Ginny was hospitalized, and once more George had to put our plans on ice, as he took care of the household and attended his wife and met other professional deadlines. When she died on April 5, 2014, the life seemed to go out of George. His health declined precipitously, all the while he kept saying he would return to our project soon. He died six months later, on October 21st.

Our collaborative project to please a shadow was now mine alone. And now I must please two shadows.

It was only after his death that I fully realized the stature of the man. So many of us focused on his high-profile work with the celebrity poet Brodsky that we didn’t realize his importance as a scholar of Russian philosophy and culture. “His personal presence in our midst was a gift, not to be replaced; his influence on the field is by now indelible,” wrote Grier.

He published more than 300 articles, chapters in anthologies, encyclopedia entries, book reviews, review articles, and, of course, translations. He authored two monographs and edited or coedited six anthologies. He wrote authoritative studies of Hegel, Spinoza, and Whitehead, and made notable contributions to understanding Marx and Marxism. He inspired a generation of younger scholars, poets, and translators—including Ishov and Mashinski, the two who were able to keep up with his exacting, tireless correspondence. What’s lesser known is how greatly this quiet Bryn Mawr professor supported scholars around the world who were working with Russian poetry and Brodsky in particular.

The Kline family encouraged me to continue with the project that had been interrupted by the death of its subject and collaborator. They were generous with their help in a time of great family upheaval and trauma. At my request, several big boxes of articles, drafts, translations, correspondence, emails, newspaper clippings, photos, and more arrived at my Palo Alto home. The family’s graciousness during a time of stress was much appreciated.

With these records, and my transcripts and notes, I continued our conversation post-mortem—in some ways easier, without the crackling of bad Skype connections and accumulating mp3 files, without the exhaustion, the background noise of domestic emergencies that had become increasingly frequent and urgent.

I began to sense in this staid Unitarian a profound religiosity beneath the surface.In other ways the task had become harder, too, as I became the editor of a unique fragment of literary history, as well as the interlocutor within it. As George had wished, I blended our conversations with other material to fill in vital parts of his story, adding an additional layer of complexity to an already complicated project. Over the weeks and months, I transformed our brief, piecemeal talks into the conversations we could have shared, had time and circumstances allowed.

I relied on a vast range of articles, interviews, letters, emails, and other records. With one of the boxes the family had sent, filled with his tiny 2.5” x 3” datebooks, I could confirm appointments from the crabbed, often inscrutable penciled scrawls on the fading pages. I pored over the holdings at Yale’s Beinecke Library, which holds many of his important papers. My fondest hope is that I have included enough to restore the legacy of an overlooked figure in the Brodsky circle, a man who has not gotten his due.

I remember the sting of his criticism, and came to wonder if there was any translation that he truly liked without qualification; he criticized even close friends. Yet I found among his papers his generous appraisal of me for a 2007 National Endowment of the Humanities application: “I always read Cynthia’s writings with real pleasure; they are uniformly concise, lively, and richly informative. Poet Kay Ryan noted perceptively that Cynthia’s writing about poetry ‘has the sting and bite of poetry in it.’ This is high praise, but strikes me as fully justified. As an editor she is unusually conscientious, persistent, and resourceful.” My road was longer without this kindly scholar prodding me onward.

During the initial phase of the project, we received funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, under the aegis of Bryn Mawr. Much later, after George’s death, Valentina Polukhina took the project under her aegis and was able to get British Academy support for the effort. As a consequence, Valentina and I spent a week together at her home in Golders Green in March 2018, carefully combing through the final manuscript. We got to know each other much better, and her proofreading, feedback, and fine-tuning of the manuscript—and her overarching knowledge of Brodsky’s work and life—were crucial.

My fondest hope is that I have included enough to restore the legacy of an overlooked figure in the Brodsky circle, a man who has not gotten his due.One of Joseph Brodsky’s remarkable gifts was the caliber of the people he attracted around him. As George told me, “He was very good at—how shall I put it?—judging people and feeling almost at first contact that they were good people, serious people, intelligent, knowledgeable, perceptive, and he wanted to be with them, to be their friends. There weren’t very many people like that.” He cited the instant rapport with Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, Mark Strand, Dick Wilbur, Susan Sontag, and Bob Silvers, and “probably a couple of others that I’ve forgotten.” One of the people he had forgotten was, of course, himself. Steadfast, meticulous, and quietly loyal George is usually not mentioned with this crowd. But he had qualities many of us couldn’t touch.

Later, the Russian poet was asked, “When you first came to the United States, what surprised you most? It’s been said that you drew some of your expectations from reading Robert Frost, that you felt America would be more rural than you found it.”

He replied, “Not more rural, but I thought that the people would be less vocal, less hysterical, more reserved, more prudent with their speech.” Surely he found those very qualities of restraint and dignity in the man he had met way back in Leningrad, August 1967, who would become his first serious translator.

During the time we were doing our interviews, George had suggested this sentence from writer Igor Yefimov for an epigraph: “Everyone who had any connection with Joseph Brodsky knows that he is doomed to think and talk about the poet to his own final day.” Then he added, “It would apply to both of us, after all.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Man Who Brought Brodsky into English: Conversations with George L. Kline. Used with the permission of the publisher, Academic Studies Press. Copyright © 2021 by Cynthia L. Haven.