Translating at the Blurred Edge of Memoir and Fiction

K.E. Semmel on Mathilde Walter Clark’s Lone Star

I once interviewed Michael Chabon. To prepare, I read nearly every book he’d ever written. His latest novel was Moonglow, and I spent days absorbed in its pages. In that novel, readers get a cinematic depiction of the extraordinary life of Chabon’s grandfather, a World War II soldier and engineer obsessed with rockets, as narrated by a character named “Mike.” It’s a captivating novel that reminded me of Philip Roth’s Zuckerman novels, books where the boundary between fiction and memoir is deliberately obscured. Between the author’s life and the author’s invention.

In an interview—not mine—Chabon discusses this boundary-blurring and his desire to write a novel with the authenticity of a memoir. Many readers, he notes, often wonder whether scenes or stories in a novel are fact or fiction.

“I decided to incorporate that expectation of readerly behavior into the book itself and freely salt it with all kinds of so-called clues that could be read by the reader who was alert to these things,” he says. “All of those clues are equally fictional. It’s a kind of a game, playing with the reader’s expectations.”

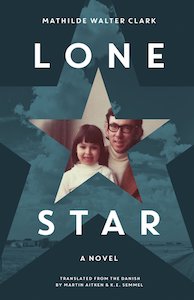

Something similar happens in Lone Star, Mathilde Walter Clark’s first novel to be published in English, co-translated by Martin Aitken and me: readers find the life of Mathilde Walter Clark, her father John Clark, and all the moons (Mathilde and her siblings and stepmother) circling—often unhappily—in his orbit, as narrated by a character named Mathilde Walter Clark, who is writing a book on the subject, a book that would eventually be titled Lone Star. Is it fiction? Autofiction? Or is it some third thing, a fictionalized memoir?

During the translation process, Mathilde and I exchanged periodic emails, the typical correspondences between translator and author. What do you mean here? Is it accurate to say—? Does this capture your meaning—? Are you okay if I—? But I’ve never met Mathilde in person, and I don’t know her life story except how I perceive it from this novel. But it hardly matters. Whether “real” or not, what matters is that Lone Star reads like a blend of fiction and memoir: a narrative derived from events and memories in the writer’s life.

You may find examples of this kind of thing in other contemporary novels, depending, admittedly, on how you choose to read them, like Ayad Akhtar’s Homeland Elegies, Justin Torres’s We the Animals, Kate Zambreno’s Drifts, and even, going further back, Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, and Fay Weldon’s Mantrapped. This is by no means an exhaustive list, of course, but my starting point is that each book is marketed as fiction, not nonfiction, as in the case of Maxine Hong Kingston’s China Men, which won the 1981 National Book Award in the latter category. The point is, it’s here in this fuzzy zone of fiction and memoir that Lone Star gets its narrative juice.

*

I lucked into co-translating Lone Star. Martin Aitken, one of the very best Danish to English translators working today, had done a large sample translation of around 20,000 words. After reading this sample, Will Evans at the Dallas-based publisher Deep Vellum bought the book. As you might glean from the title, it is a perfect marriage of book and publisher, since half the novel is set in Texas and is entrenched in that state’s history and culture. Because Martin is a gifted translator and in constant demand, he was too busy to finish the rest of the book, which amounted to approximately 100,000 additional words, and he asked me if I was interested. As soon as I immersed myself in the pdf version Will sent me, I specifically recalled my experience reading Moonglow and I knew without a doubt that I would say yes to the project. Like Chabon, Clark has an ability to render complex sentences and imagery in compelling and vivid language, and the chance to be one of two people to transmit this incredible prose into English was simply too great to pass up.

On the surface, Lone Star offers a relatively straightforward narrative. Mathilde Walter Clark is writing a book about her family, though the subject matter principally involves her relationship to John Clark, her father, an internationally recognized professor of physics at Washington University, in St. Louis. He lives with his Dutch wife and their children in a vast and peculiar house that becomes a kind of character in the book.

“I can’t say how many times I’ve tried to write about my dad’s house,” Mathilde writes. “Nor can I say how many times I’ve entered it in my dreams, gripped by a nameless terror, in search of my dad and my siblings. Sometimes I feel that it wasn’t simply a house, a thing, a reference point or geographical location that framed my family’s life, but an independent character that influenced us, and that even now, at a vast distance of time and space and dreams, exercises its demonic power over me so that I am doomed to try and describe it again and again—and fail again and again.”

What matters is that Lone Star reads like a blend of fiction and memoir: a narrative derived from events and memories in the writer’s life.

For readers, this house may seem like a wonderfully bizarre mishmash of the House of Usher and the von Trapp palace in The Sound of Music: a place where joy and misery comingle like awkward guests at a child’s birthday party. Mathilde, the product of a brief marriage between her Danish mother, Karin, and this distant star of an American father, worships John Clark from afar in the series of Copenhagen apartments she shares with her mother.

When she’s old enough to travel alone, Mathilde boards a plane and flies to St. Louis for what turns out to be a remarkable summer, which becomes multiple remarkable summers. It’s in the aforementioned house that Mathilde, this Danish child with her European sensibilities, experiences Midwestern America in all its gritty pomp and glory, living among a decidedly eccentric family. She writes candidly of her family life in St. Louis, pulling no punches and sparing nothing, not even herself, as these scenes draw out the deep, inky complexity of American life viewed through the eyes of an observant Danish-American girl.

At its core, however, Lone Star is about one woman’s efforts to get close to her father, to glide into his magnetic field and join his orbit. The lone star of the title has a dual meaning. John Clark, the professor of physics, has a penchant for diving deep in his thoughts on matters of universal significance—as you might expect of someone whose research interests include Many-Body Theory and Dense-Matter Astrophysics—and being physically and emotionally distant. He’s the lone star, but he’s also from the Lone Star State, and it’s to Texas that Mathilde, now an adult, takes a memorable trip with her father, getting to know him and his history (which is bound up in Texas history). And it’s here, in Texas, where Mathilde’s quest to connect with her father reaches its inevitable conclusion. The membrane that separates father and daughter is pierced, even if temporarily, and the vast distance between them is closed.

As I translated my portion of Lone Star, I was taken by the way Mathilde clearly plays, like Chabon, with readerly expectations. It is a novel, yes, but what else? A fictionalized memoir? Maybe readers will prefer to think of it as autofiction, a term I’ve never personally cared for. It’s fun stuff to think about. But in the end, these are just terms, categories to label books so they can be placed on bookstore shelves. Whether you read for fact or for fiction, Lone Star is a great story, lush and lively and full of messy truths.

__________________________________

Lone Star is available from Deep Vellum Publishing, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken and K. E. Semmel. Copyright © 2021 by Mathilde Walter Clark.

K. E. Semmel

K.E. Semmel has translated more than a dozen novels from Danish. He's also a fiction writer, with stories published in Ontario Review, Aethlon, and Necessary Fiction. Someday, he hopes, his own novels will find publishers. Learn more at kesemmel.com.