Writing a Fictionalized Apocalypse Does Not Prepare You For a Real One

Geoff Rodkey on Accepting the Realities of Civilization-Ending Calamity

It’s not like I wasn’t aware of the risk.

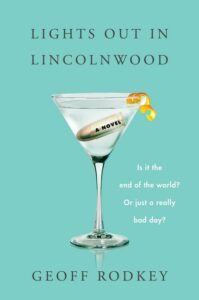

Back in 2019, when I started writing Lights Out in Lincolnwood—a dark comedy about a privileged-but-hapless family’s attempts to navigate the sudden collapse of their wealthy New Jersey suburb’s entire technological infrastructure—I had a nagging sense that I should finish it as fast as possible, because the daily news cycle had started to feel ominous enough that I was concerned an actual apocalypse might arrive while my novel about a fictional one was still in copyediting.

Depending on how loosely you define “apocalypse,” that’s more or less what happened. While civilization hasn’t fallen (yet), in the 18 months since my agent first sent the Lincolnwood manuscript to publishers, the book’s plot points have started to resemble a current-events bingo card: February’s power and water outages in Texas, the armed insurrection by suburban white guys on January 6, and the looting of my Manhattan neighborhood during last summer’s otherwise peaceful protests all have their fictional equivalents in the story.

And while I do take some pride in having written “what happens when we run out of toilet paper?” into a character’s internal monologue four months before the global toilet paper shortage of March 2020, at this point I’m just praying nothing else in the book manifests in real life. It’s a lot less fun to live in a dystopia than it is to imagine one.

That said, recent events have added some urgency to the story’s central dramatic question: if the complex systems we depend on for our basic human needs suddenly disappear, how would we handle it?

Personally, I’d be pretty screwed. I learned this lesson firsthand in 2012, when my family’s tenth floor apartment in lower Manhattan lost power and water for four days after Hurricane Sandy. While the decade-old trauma of 9/11 had left us with a decent stockpile of bottled water and a hand-crank radio (along with some utterly useless radiation pills, plastic tarps, and duct tape that we acquired in a panic during a 2002 Homeland Security Orange Alert terror scare), we weren’t otherwise provisioned for mass systemic disruption, and we found ourselves quickly reduced to a kind of 21st-century urban foraging.

The daily news cycle had started to feel ominous enough that I was concerned an actual apocalypse might arrive while my novel about a fictional one was still in copyediting.Every morning, I’d haul buckets of water—drawn from a trash barrel in the lobby that our building’s super had filled by illegally opening a street hydrant—up nine flights of stairs so we could flush the toilet. Then we’d march our three kids thirty blocks north to Midtown, where the power was still on. We’d feed the kids sandwiches at a deli, continue on to a friend’s apartment to shower and recharge our phones, then scurry back home, Omega-Man-style, before sunset plunged the streets into darkness. After boiling a pasta dinner on the (mercifully still functional) gas range, we’d go to sleep at seven, because there was nothing else to do if we didn’t want to deplete our flashlight batteries.

While Hurricane Sandy was catastrophic for a lot of people, we came away unscathed. There was none of the horror, grief, or months-long anxiety that had accompanied 9/11. Instead, we mostly experienced Sandy as a particularly annoying snow day. This was especially true of our sons, who at 12, 10, and 7 were all too happy to miss school and eat pasta all week, and felt distress only to the extent that they couldn’t recharge their iPods.

But in the years after Sandy, I was intermittently haunted by the question of how we’d survive any systemic disruption that was more widespread or less temporary. This was a whole other category of fear than the one occasioned by 9/11. Terrorism might be fatal, but at least it’s usually over with quickly. On the other hand, any calamity that left us physically unharmed but cut off our supply of basic resources could result in an agonizingly slow demise, over the course of which my wife would have almost unlimited hours to berate me for having fucked up by not planning ahead.

The thing is, though: survivalist prep is uniquely challenging in a New York City apartment. There are only so many gallons of Poland Spring I can cram into that cabinet above the fridge. When those run out, what do we do for drinking water? Once we finish the pasta, rice, and beans, how will we feed ourselves if the local stores quit stocking their shelves? Whatever food and water we can get our hands on will presumably be astronomically priced—but how will we pay for it once we run through all of our cash? Most of our assets are just numbers on a screen. If the screens go black, we’re effectively bankrupt until the power comes back on.

These are scary thoughts, to which a wiser or more responsible person might have responded by relocating to a rural area, digging a well, and acquiring livestock and firearms.

I responded by writing a book. Even less helpfully, I made it a comedy. (An existentially serious one, but still.) Over the long haul, this was probably a maladaptive response. But in the short term, shoving all of my anxiety and inadequate disaster planning onto the plates of a bunch of fictional characters at least felt emotionally liberating, even as it did nothing to actually address the underlying predicament.

Having experienced both mass terrorism and natural disaster, and mindful that I was writing a comedy, I made the inciting catastrophe in Lights Out in Lincolnwood as bloodless as possible: a sudden, massive electromagnetic disturbance that fries any device with a circuit board. This effectively destroys all of modern society’s food, water, communications, and transportation systems, stranding the four members of the Altman family and the rest of their genteel suburb in a world that no longer functions, but still looks more or less the same as the old one.

I also limited the book’s action to just three days. At any longer time scale, the comedy would inevitably curdle into horror, and that wasn’t the kind of story I was looking to write. Instead, I wanted to explore the psychological and social dislocations of an event that initially seems to the book’s characters like it could fall anywhere on the spectrum between a civilization-ending calamity and a temporary pain in the neck.

In that respect, it’s a little like those first days in March 2020, when everything shut down, and we all asked ourselves, “How long is this going to last?”

Like most of us, I never saw the pandemic coming. When I spent 2019 frantically working to get the book finished ahead of the apocalyptic undercurrents in the news, it was mostly forest fires and fascism that worried me. Viruses didn’t even make the list.

And when the lockdown arrived, forcing our now college-aged sons back into 24/7 cohabitation with us, the truly scarce resource didn’t turn out to be drinking water or food, although our post-Sandy pasta stockpile did come in handy. It wasn’t even toilet paper. It was bandwidth.

In the end, my family muddled through covid without any apparent long-term damage, for which I’m very grateful. And since the words virus, mask, and Zoom never appear in it, Lights Out in Lincolnwood wasn’t entirely scooped by reality. But the experience of writing the book, the events of the past 18 months, and the staggering rise in real estate prices for prepper-friendly plots of land upstate have left me increasingly fatalistic about any future apocalypse.

If society collapses, our apartment’s going down with it.

______________________________________

Lights Out in Lincolnwood is available now from Harper Perennial.