Tracing the Romance Genre’s Radical Roots, from Derided “Sex Novels” to Bridgerton

Hilary A. Hallett on Reclaiming “Trashy” Romances

With the new season of Bridgerton airing, the topic of the romance genre’s purpose, perils, and pleasures has become a topic of conversation, once again. Long critically reviled as trash, the popular romance has been blamed for a variety of women’s readers ills, including reconciling them to the patriarchy by promising women happy endings for their pains. In recent years, the genre’s most important gatekeeper, Romance Writers of America, came under fire for celebrating novels that perpetuated painful racial stereotypes, treated historical topics like genocide insensitively, and failed to recognized the work of authors of color.

But the romances and writers sparking much of the current talk also suggest the time for a cultural reset may have arrived. The powerhouses behind Bridgerton’s success—television producer Shonda Rhimes brought Julia Quinn’s novels to Netflix—along with some of the genre’s most notable spokeswomen of late, including real-life political superheroine Stacey Abrams and Fated Mates podcaster Sarah MacLean, are pointing the way toward a reassessment that delights this cultural historian by harkening back to the genre’s radical roots. For most forget that the fundamental purpose of the modern romance when it first developed was to explore the force of women’s desire and to expose the many barriers thrown up to prevent women’s exercise of free love.

The modern romance lays its taproots in a scandalous new bucket of fiction called the “sex novel” that troubled the censorship codes of Anglo-America. An often-censorious term coined by journalists that became fashionable after 1905, sex novels’ more explicit focus on the problems and pleasures associated with sex was not just unorthodox, but judged dangerous to women’s health and racial purity, accordingly to many elites. These books’ emphasis on sexual psychology and interior sensations, as much as stimulation and particular acts, differed from existing so-called pornographic literature (aimed at men).

Sex novels challenged the genteel code of Anglo-Americans’ literary culture—which by the early 20th century permitted only messages of idealization, uplift, and refinement about the body—enforced by purity associations run by men like Anthony Comstock and squeamish publishers, editors, and critics. But the commercial success of sex novels made them difficult to suppress.

Sex novels were not only written about but also, many assumed, for women—in part because women read more fiction than men. Other noteworthy examples included Somerset Maugham’s Mrs. Craddock (1903); May Sinclair’s The Helpmate (1907); Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks (1907); Henry de Stacpoole’s The Blue Lagoon (1908); H.G. Wells’ Anne Veronica (1909); Hupert Wales’ The Yoke (1908); Cicely’s Thompson’s Just to Get Married, (1911) and Victoria Cross’ The Greater Law (1914). The term “best-seller” first circulated widely around many of these books, whose commercial success helped to drive the expansion of the publishing industry more than a century ago.

Although both sexes composed these “bad books,” critical attacks often focused on the ones by women writers in a period marked by their increasing prominence on the literary lists. “The record of fiction of the last 20 years is full of cases where women have written books that no man would have dared signed—books that were naked and unashamed,” declared The New York Times in 1907. Concern about the immoral influence of these women writers and readers on the English novel ricocheted back and forth across the Atlantic. “Readers—chiefly women—who make the fortune of English fiction” embrace of this “Fleshy School of Fiction” spelled the end of the “tenderhearted tradition of Scott, Dickens, and Thackeray” warned “A Man of the Letters” in the London Bookman.

“Why is it that when women writers of the modern school deal with passion, they succeed only in ‘nastifying it?’” demanded the eminent American critic William Marion Reedy of likely the most notorious work, Three Weeks (1907). Written by the British society author Elinor Glyn, the “free love” novel celebrated an older, unhappily married woman’s sexual education of a young Englishman during their titularly short affair. The novel got Glyn ostracized by her fashionable friends, but its enormous success helped to splinter the genteel code years before D. H. Lawrence’s more celebrated troubles with the censors.

The fundamental purpose of the modern romance when it first developed was to explore the force of women’s desire.

Sex novelists laid the groundwork for what became the romance genre by the 1920s, which placed new emphasis on the importance of sexual compatibility in finding the right mate. Their franker treatment of female sexual desire and the often ubiquitous problems that sex generated for women helped to explain how novel reading quickly became “the chief method for the average man and women to get knowledge of life,” as an expert declared during the 1928 obscenity trial of the lesbian urtext, The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall. Yet the sociology of knowledge, and aesthetic judgments that deemed the work of women authors writing about sex as trash, have erased their role in moving literature toward greater frankness about reckoning with the expression of sexual desire on the page.

Flash forward a century. Even before Bridgerton, Shondaland offered a progressive sexual education that offered fantasy-worthy solutions to well-worn explosive topics in American society. By routinely exposing viewers to a world where same-sex and cross-race sexual attraction are ordinary, Grey’s Anatomy, Scandal, and How to Get Away with Murder treat these relationships as mundane rather than as fetishized oddities and commodities, or as an occasion to make political arguments (however worthy and necessary those may be). As a white women married to a Black man for 20 years, it felt revolutionary to enter this Black women’s fictional universe and be told: it’s okay to put down the enormous historical baggage surrounding relationships like yours for an hour and enjoy a world that neither erases nor revolves around race.

Rhimes has been vocal about creating female characters whose sexual empowerment might encourage her three daughters to grow up to have “amazing sex.”

It is also impossible to miss how powerfully her shows repudiated what the feminist film historian Laura Mulvey first called the male gaze in ways that echoed the first sex novels. “In Shondaland, in the love scenes, the boys have to be the ones to take their clothes off, and the women, the girls can do whatever they want,” is how Scandal star Tony Goldwyn described her approach. Rhimes has been vocal about creating female characters whose sexual empowerment might encourage her three daughters to grow up to have “amazing sex” and her concern about how our media codes have long permitted a destructive double standard that permits the most graphic displays of violence, much of it sexualized in nature, while balking at similarly open displays of consensual sex. All this made Rhimes a natural for translating a vision of romance to the screen that put the treacherous path to women’s sexual pleasure in the past front and center.

By turning a historical rumor about the mixed-race heritage of Queen Charlotte into fictional fact, Rhimes also adroitly addresses the problem of the blindingly white character of too many of the most celebrated romances by creating a host of Black characters up and down the social ladder of Regency society. Some scholars have accused the show of colorism for focusing on characters with lighter complexions. But that criticism seems to miss how the show’s premise—a world in which “love conquers all,” including the prejudice of whites—likely leads to a landscape in which a variety of skin colors become the natural result of the acceptance of interracial marriage and sex (rather than the exploitation of women of color under miscegenation and slave codes).

Others like Salamishah Tillet have worried that by having only the Black characters discuss the saliency of race, the show “risks reinforcing the very white privilege it seeks to undercut by enabling its white characters to be free of racial identity.” The show’s white characters’ exhibition of white privilege is undeniable; many might date the invention of the concept to their set in real life! But, to me, the article’s headline—”Bridgerton Takes On Race. But At Its Core Is Escapism”—undercuts Tillet’s thoughtful analysis by resorting to the kind of entrenched tendency to dismiss the genre as puerile entertainment.

At least some of the critical establishment seems to be catching on to why readers have made romance novels the most commercially lucrative genre for more than a hundred years. Rhimes’ fresh take, along with the advocacy of authors like Abrams and MacLean, has mostly helped less outspoken writers like Quinn get their due for providing readers with compelling narratives about sexual pleasure and politics writ large. “The real payoff in Bridgerton,” wrote Hank Stuever in the Washington Post, is how it emphasizes “the inherent sexism of the day. The sheltered young ladies of the ton… are kept ignorant of the basics of reproduction, leaving them in a constant state of potential shame, even after they are married. Menstrual cycles, the mysteries of ejaculation, the mechanics of pregnancy and gestation, the forbidden wonder of self-pleasure, the indescribable act of intercourse—nearly every plot in the show hinges on hang-ups.” But that of course does not prevent Rhimes from giving viewers perhaps the most pleasurably fleshed out—pun intended—romance between a white woman and Black man ever seen on screen.

Perhaps it’s finally time to retire the long-standing prestige gap between crime and action stories (assumedly aimed at men) and recognize that “trashy” romances (assumedly aimed at women) provide the kind of escape many of us still love.

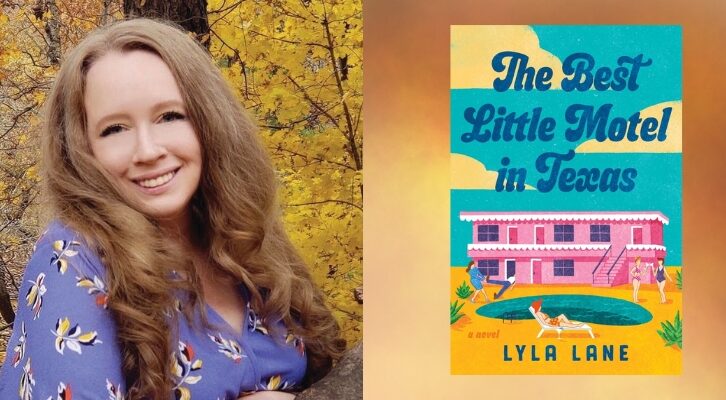

Hilary A. Hallett

Hilary A. Hallett is the Mendelson Family Professor and director of American studies and associate professor of history at Columbia University. The author of Go West, Young Women! The Rise of Early Hollywood, she has written for the Los Angeles Times. Her book Inventing the It Girl: How Elinor Glyn Created the Modern Romance and Conquered Early Hollywood is available now.