Tracing the Filipino Diaspora in the Arc of the Global Age: A Reading List

Albert Samaha Recommends Books on the Sprawling History of the Philippines and the Immigrant Experience

Over the five years I worked on Concepcion: An Immigrant Family’s Fortunes I probably spent more hours reading other books than writing my own. While extensive interviews supplied a vast collection of scenes, characters, and narrative turns, I needed guidance for discerning what overarching ideas my family’s story reflected. How did we fit into the arc of the global age? Which aspects of our journey were representative and which were unique, and why? I aspired to excavate the political and social forces that led to our exodus from the Philippines and shaped our experience in the States. For that historical research, literary inspiration, and contextual understanding, I had a deep pool to draw from.

*

Roberto Vallangca, Pinoy: The First Wave

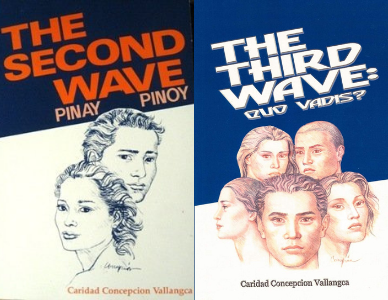

Caridad Concepcion Vallangca, The Second Wave: Pinay and Pinoy; The Third Wave: Quo Vadis

Tomas Concepcion, The Stranger

I was fortunate that many Filipino and Filipino American writers have already explored the subjects I aimed to dive into—all the more so that three of them were kin of mine who were central characters in my book: Writing a family history is much easier when your elders have recorded their experiences. My great auntie Caridad and her husband Roberto published a trilogy of oral histories chronicling three waves of Filipino immigrants in the 20th century. My granduncle Tomas, who moved to Rome in 1960, wrote a memoir, and though he published it in Italian, I helped him rewrite the English translation, which we nearly finished before he died.

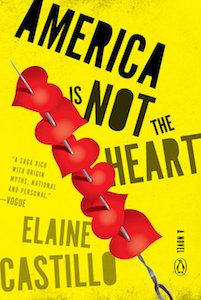

Elaine Castillo, America Is Not the Heart

Growing up in the US, I didn’t encounter a single author of Filipino descent at any point in my schooling. It wasn’t until adulthood that I began to read writers who captured stories that reflected my family’s.

Elaine Castillo’s novel America Is Not the Heart, whose protagonist flees the political instability of the Philippines to start anew in turn-of-the-millennium Bay Area, was the first book I read that presented the contemporary diaspora I was most familiar with, a suburban landscape of souped-up imports, hole-in-the-wall family restaurants, and frequent use of the word “hella.” The protagonist’s love interest, Rosalyn, with her loose hoodies, California chill, and proximity to DJs and graffiti artists, could have been one of my cousins.

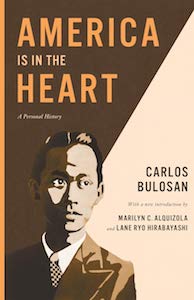

Carlos Bulosan, America Is In the Heart

Castillo’s title plays off of Carlos Bulosan’s 1946 classic, America Is In the Heart, a memoir of his years as a migrant worker in California, where he came to wonder: “Why was America so kind and yet so cruel?” Despite the racist violence and discrimination he faced, he maintained his hope that he was better off in his new land than his old one, where opportunities for a living wage were too scarce to pull him back and the American dollars he sent home went a long way.

By the time Castillo’s characters were in the States, there were fewer lynchings and more civil rights laws in the US, and Filipinos had become the fourth largest diaspora. But they arrived in America at a time of widening inequalities, and with their professional credentials invalid in the new country, they started fresh in the lower-paid service work that dominates the economy. In both books, memories of the old country hover over the bumpy landings. Nearly a century after Bulosan expressed tempered optimism in what America had to offer, Castillo cast light on the disillusionment among the Filipinos and Filipino Americans who wondered why the exodus had seemed so necessary.

From the unprofitable farm Bulosan’s family owned in the 1920s to the communist guerilla insurgency Castillo’s heroine joined in the 1980s, the conditions that drove both protagonists from the Islands traced to centuries of imperial occupation that left the Philippines underdeveloped and economically dependent on western powers. A rich tradition of Filipino literature details the ground-level consequences of imperial exploitation, together forming a vivid panorama of a colonized nation navigating the global age.

José Rizal, Noli Me Tangere

José Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere, a staple of the Philippine curriculum, had been banned by Spanish colonial authorities for its depictions of their brutality and corruption.

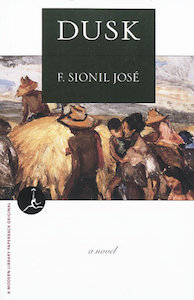

F. Sionil Jose, Dusk

In F. Sionil José’s Dusk, the final novel in a five-part saga, a tenant farmer found momentary peace when the Philippines declared independence from Spain in 1898, only for the US to seize the archipelago, inspiring him to join the armed resistance against the new invaders.

Jessica Hagedorn, Dogeaters

By the time the States granted the Islands independence in the years after World War II, American influence shaped Philippine culture and politics, and the starlets, generals, and executives in Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters aspired to assimilate into the empire underwriting their oppressive government.

Mia Alvar, In the Country

Mia Alvar’s short story collection In the Country lays out the consequences of the monopolies, embezzlement, and cronyism under US-backed dictator Ferdinand Marcos: a cratered economy that left many too poor to afford daily meals and compelled people to find work overseas, where they lived away from their families for months and often endured abuses as housekeepers, drivers, nurses, and deckhands around the world.

Gina Apostol, Insurrecto

Gina Apostol’s Insurrecto casts its eyes across that turbulent history, contrasting the Filipino version of events with the one America tells.

Cesar Adib Majul, Muslims in the Philippines

The conquerors keep the records—on the Islands, Spain erased traditions that had lasted thousands of years and America wrote the textbooks that educated schoolchildren. In recent decades, though, Filipino and Filipino American historians have centralized the Philippine perspective.

Cesar Adib Majul’s Muslims in the Philippines offers a comprehensively researched account of the sultanate dynasties that ruled the archipelago’s southern island and resisted Spanish conquest for three centuries.

Teodoro A. Agoncillo, Milagros Guerrero, and Oscar

Alfonso, History of the Filipino People

In History of the Filipino People, a book that has been used in many Philippine schools, Teodoro Agoncillo, Milagros Guerrero, and Oscar Alfonso don’t shy from calling Spanish officials “crooked,” capturing the nationalist spirit rising at the time it was written, less than two decades after independence.

Luis H. Francia, A History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos

For a more straightforward and more recent survey of the archipelago, Luis H. Francia’s A History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos spans from pre-colonial history to the early 21st century, stitching together the characters who resisted and collaborated, framing their motives through the conditions that produced them.

Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, Little Manila Is In the Heart

For a glimpse of the early Filipino immigrant experience, Dawn Bohulano Mabalon’s Little Manila Is In the Heart presents a granular account of the Filipino community in Stockton, California, from its formation as a sanctuary in an era of “No Filipinos or dogs allowed” signs to its displacement during the urban redevelopment projects of the post-war decades.

Ambeth R. Ocampo, Rizal Without the Overcoat

To help frame how history is remembered, Ambeth R. Ocampo’s writing collections, notably Rizal Without the Overcoat, humanizes the nation’s larger-than-life figures, slicing through the mythology that tends to harden with time.

Catherine Ceniza Choy, Empire of Care

A growing field of social scientists has sharpened the collective understanding of how the Filipino diaspora has spread and adapted to new environments—and answered questions I’d long pondered.

Why are there so many Filipino nurses in the US? From the country’s years as an American territory, they spoke English and attended American-built training programs, and as Catherine Ceniza Choy’s Empire of Care details, those colonial years established an economic dependency that compelled waves of medical professionals to decamp for a distant land where they faced discrimination while their homeland’s health care system sputtered.

E.J.R. David, Brown Skin, White Minds

Why was Filipino culture so absent from the American landscape even though we comprise the fourth-largest immigrant diaspora? Navigating three centuries under colonial authority, our ancestors mastered the art of assimilation, and over time that survival tactic birthed a mentality that elevated western traditions over ancestral ones, a collective psyche that helps perpetuate the imperial hierarchy upholding colonial caste systems, as E.J.R. David unpacks in Brown Skin, White Minds.

Anthony Christian Ocampo, The Latinos of Asia

Why did my family shop in grocery stores filled with Chinese people but worship in churches filled with Mexican people? As Anthony Christian Ocampo’s The Latinos of Asia explains, the archipelago’s history at the nexus of eastern commerce and western colonization created a layered ethnic identity that left many in our US-raised diaspora well-equipped to blend into the social ecosystems around us but unsure what defined our Filipino identity, what collective experiences distinguished us from the communities we assimilated into.

Matt Ortile, The Groom Will Keep His Name

While our diaspora traces to a shared history, it contains countless strands veering off in many directions. The story I chronicle in Concepcion is one thread in a vast tapestry. Other writers of Filipino descent have unspooled their own stories, an expanding canon showing the wide-ranging experiences within our communities.

In his essay collection The Groom Will Keep His Name, Matt Ortile examines the social dynamics and model minority fallacies he stepped into upon landing in the US as a child.

Meredith Talusan, Fairest

In her memoir, Fairest, Meredith Talusan interrogates the colorism and gender conventions she encountered on her journey from child star in the Philippines to Ivy League graduate in America.

Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror

Jia Tolentino’s essay collection, Trick Mirror, presents a second-generation narrator grappling with the deluding culture of a country where perception outweighs reality.

Cinelle Barnes, Monsoon Mansion

In Monsoon Mansion, Cinelle Barnes recounts her family’s efforts to maintain their dwindling wealth in the Philippines at a time when more and more Filipinos were looking for opportunities overseas.

Jose Antonio Vargas, Dear America

Jose Antonio Vargas’s Dear America details the indignities and absurdities of living as an undocumented immigrant in the US.

Grace Talusan, The Body Papers

In The Body Papers, Grace Talusan traces the generational traumas weighing on her immigrant childhood but left unspoken in a diaspora accustomed to keeping silent about our troubles.

__________________________________

Concepcion: An Immigrant Family’s Fortunes is available from Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Albert Samaha.