The Unearthly Glamour of Swans: On the Origins of Truman Capote’s Unpublished, Scathing Roman à Clef

Laurence Leamer Looks at Capote’s Fascination with Fabulously Rich Women

For years, Truman Capote had been proudly telling anyone within hearing that he was writing the “greatest novel of the age.” The book was about a group of the richest, most elegant women in the world. They were fictional, of course… but everyone knew these characters were based on his closest friends, the coterie of gorgeous, witty, and fabulously rich women he called his “swans.”

Truman understood what these women had achieved and how they had done it. They did not come from grand money but had married into it, most of them multiple times. Their charms were carefully cultivated, and to the outside eye, they seemed to have everything… but for most of them happiness was an elusive bird, always flying just out of sight. This was something the 50-year-old Truman knew about. He was calling his novel-in-progress about the swans Answered Prayers, following the saying attributed to Saint Teresa of Ávila: “There are more tears shed over answered prayers than over unanswered prayers.”

In 1975, Truman was one of the most famous authors in the world. Even those who had not read a word of Truman’s writing knew about the diminutive, flamboyantly gay author. His 1958 novella, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, had been widely celebrated, and the movie starring Audrey Hepburn was a sensation when it premiered in 1961. Millions of Americans had devoured his masterful 1966 true crime book, In Cold Blood, and countless more saw the 1967 film adaptation. The “Tiny Terror,” as Truman was called, was a fixture on late night television, mesmerizing audiences with his outrageous tales.

Truman’s richly evocative style and the astonishing global success of In Cold Blood several years before had created an audience that waited impatiently for his latest work. Answered Prayers would be a daring literary feat, an exposé of upper-class society that blended the fictional flourishes of Breakfast at Tiffany’s with the closely observed narrative nonfiction of In Cold Blood. No one had ever gotten that close to these women and their elusive, secretive world. Marcel Proust and Edith Wharton had written classic novels focused on the elite of their ages, of course, but they were children of privilege, raised in that world and of it.

Truman, on the other hand, was an interloper. Since coming from a small town in Alabama decades earlier, he’d carved out a unique spot in New York society: a scathingly sharp, always entertaining guest whose charm opened the doors to the most exclusive circles… and whose eyes and ears were always open and observing what he saw there.

As much as Truman was drawn to the beauty, taste, and manners in that world of privilege, he was repulsed by its arrogant sense of superiority and ignorance of life as most people lived it. Life had a way of intruding and teaching hard lessons. The tension between those two beliefs would create his immortal book.

Crucial to Truman’s masterpiece would be evoking the world of the swans. And that world could be summed up in one word: sumptuous. These women knew the power of money (what it could buy, what it could compensate for). But despite what their spiteful detractors might have suggested, their allure wasn’t due to money alone. “It may be that the enduring swan glides upon waters of liquefied lucre; but that cannot account for the creature herself,” Truman wrote in an essay in Harper’s Bazaar in October 1959. His swans were wealthy, yes. But that wasn’t all.

Truman chose his swans as if collecting precious paintings that he wanted to hang in his home for the rest of his life.To Truman each swan was the personification of upscale glamour in the postwar world. She was the confluence of a number of unique factors. Her good looks and elegant demeanor made both men and women turn and look at her. A woman could not simply buy her way into this. “If expenditure were all, a sizable population of sparrows would swiftly be swans,” he wrote. He would reach beyond the gold, the silver, and the jewels and see his swans as they truly were. Each woman had an extraordinary story to tell, and Truman was the only one who could tell them.

The swans were all famously beautiful as well—was it their looks that defined them?

Not so, Truman maintained. The swan was lovely, yes, but it was not just her beauty that created the attention—rather, it was her extraordinary presentation. Many of these women had been celebrated for years, even decades, not just for their looks but for their unique style. A swan had not only the money to buy her clothes from the finest couturiers but the elegance to wear them at their best. Other women imitated her fashion sense, and men eyed her with appreciative (and often covetous) eyes.

But a swan’s beauty wasn’t just skin-deep—she was clever, cunning even. Her wit and patter intrigued even such a merciless critic as Truman. She knew that while looks could capture a man’s attention, it took intelligence and wiles to keep it. And keep it she would, at all costs. It took discipline and focus, Truman knew, to create such a persona and keep it up decade after decade, long after other women gave up the illusions of youth.

There were probably no more than a dozen women who Truman could have deemed true swans. They were all on the international best-dressed lists, they were each celebrated in the fashion press and beyond, and they all knew one another. These women had no idea—and neither did Truman—that they were a vanishing breed, a species that would live and die in one generation.

Truman chose his swans as if collecting precious paintings that he wanted to hang in his home for the rest of his life.

Barbara “Babe” Paley was first in Truman’s mind. She was often called the most beautiful woman in the world, and Truman just liked looking at her, admiring her incredible panache.

Nancy “Slim” Keith was a stunning California girl with a far more causal style than Babe. Droll and supercharged, she could match Truman bon mot for bon mot.

In the Renaissance, Pamela Hayward would have been renowned as one of the great courtesans of the age. In the modern era, there were other terms for such conduct. Truman was first taken aback by Pamela’s shameless behavior to get and keep the attention of the rich men upon whose good graces she depended. But in the end, he was seduced by her talents and charm, as so many had been before.

The Mexican-born Gloria Guinness was the only other swan who compared to Babe in her beauty. Married to Loel Guinness, one of the richest men in the world, Gloria lived a life of splendor in homes across the world. Fiercely intelligent and perceptive, there was nothing Truman could not discuss with her.

Truman saw Lucy Douglas “C.Z.” Guest standing tall and elegant at a bar between acts on opening night of My Fair Lady on Broadway in March 1956, and he knew he had to make her his friend. Born a Boston Brahmin, C.Z. had an inbred self-confidence rare in Americans. An elitist of the first order, she was roundly dismissive of people she thought unworthy. But if she liked you (and she liked Truman), she was a wonderful friend.

Of all the swans, none came from such an exalted background as Marella Agnelli, who was born an Italian princess. Married to Gianni Agnelli, the head of Fiat and Italy’s leading businessman, this highly literate, creative woman was in some senses Italy’s First Lady.

Lee Radziwill had more than a casual familiarity with First Ladies since her older sister, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, had actually been one. Truman thought Lee far more beautiful and a far better (and more interesting) person than her famous sister, and he devoted himself to her more than he did to any of the other swans.

Truman sailed on their yachts, flew on their planes, stayed at their estates, supped at their tables, and heard their most intimate tales. Heterosexual men loved to sleep with these women, yes, but they often were not deeply interested in them as human beings. Truman was. He appreciated what they did with their lives and the various, complex ways they made themselves such creatures of elegance. What some dismissed as trivial and self-indulgent, Truman saw as a kind of living art.

A brilliant observer of the human condition, Truman had spent as much as two decades with some of these women, two decades to explore the deepest recesses of their lives, two decades to understand them. He appreciated the challenges of their star-crossed lives, what they faced, and how they survived. He had everything he needed to write about them with depth and nuance, exploring both the good and the bad, the light and the darkness. Answered Prayers would be his masterpiece, he knew—the book that would give him a place in the literary pantheon alongside the greatest writers of all time.

Although Truman had hinted at the novel’s genius for years, celebrity is a cacophony of distractions, and it was taking him longer to write it than he’d promised it would. Far, far longer. His publishers were growing anxious, the advance payment they’d given him had long since run out, and the literary elite were starting to whisper that maybe this book wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. Maybe Truman wasn’t even writing at all.

This maddened him. These feckless critics just didn’t understand his process. To show them, he published a chapter of Answered Prayers in the June 1975 issue of Esquire. When “Mojave” had less of an impact than he thought it would, Truman decided to publish a second devastating chapter, a “proof of life” missive that would reveal just how explosive and revolutionary his new book was. One that would return him to the glory days of his literary stardom, when he was celebrated beyond measure.

During the summer of 1975, Truman showed his authorized biographer, Gerald Clarke, the excerpt, “La Côte Basque ’65,” he planned to run in the November issue of Esquire. Truman had said he was writing a tome worthy of sitting between Proust and Wharton—one that would offer an intimate, wise, and perceptive look at the follies and foibles of mid-century, high-society life. Clarke was… underwhelmed. Although the story that Truman handed to Clarke was written in the author’s exquisite style, it was little more than a string of gossipy vignettes, repeating the kinds of ugly stories that were whispered at elite dinner parties.

Stories, Clarke easily realized, that were mainly drawn directly from the lives of Truman’s beloved swans and their friends. Clarke could tell immediately who most of these subjects were—the swans, after all, were some of the most famous and feted women of the day—and those he could not decipher Truman told him. Clarke had a largely candid relationship with his subject, and he told Truman that those written about in this way would recognize themselves immediately… and they would not be happy.

“Naaaah, they’re too dumb,” Truman said. “They won’t know who they are.”

__________________________________

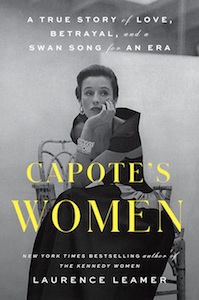

From CAPOTE’S WOMEN: A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era by Laurence Leamer, to be published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Leamer.