Towards a Definition of the Brown Commons

From José Esteban Muñoz's Posthumously Published The Sense of Brown

“Brown commons” is meant to signify at least two things. One is the commons of brown people, places, feelings, sounds, animals, minerals, flora, and other objects. How these things are brown, or what makes them brown, is partially the way in which they suffer and strive together but also the commonality of their ability to flourish under duress and pressure. They are brown in part because they have been devalued by the world outside their commons. Their brownness can be known by tracking the ways through which global and local forces constantly attempt to degrade their value and diminish their verve.

But they are also brown insofar as they smolder with a life and persistence: they are brown because brown is a common color shared by a commons that is of and for the multitude. This is the other sense of brown that I wish to describe. People and things in the commons I am rendering are brown because they share an organicism that is not solely the organic of the natural as much as it is a certain brownness, which is embedded in a vast and pulsating social world. Again, not organic like a self-sufficient organism, but organic in that the world is brown as the objects within that world touch and are copresent.

The brown commons is not about the production of the individual but instead about a movement, a flow, and an impulse to move beyond the singular subjectivity and the individualized subjectivities. It is about the swerve of matter, organic and otherwise, about the moment of contact, and the encounter and all that it can generate. Brownness is about contact and is nothing like continuousness. Brownness is a being with, being alongside. The story I am telling about a sense of brown is not about the formation of atomized brown subjects. It is instead about the task, the endeavor, not of enacting a brown commons but rather of knowing a brownness that is our commonality. Furthermore, the brownness that we share is not knowable in advance. It is not reducible to one object or a thing, so the commons of brownness is not identifiable as any particular thing we have in common.

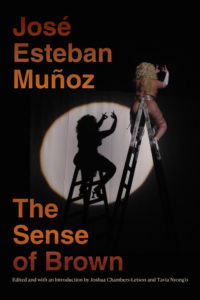

Nao Bustamante performing Given Over to Want, Autentika (Sculpture Quadrennial Riga), No New Idols performance festival, Riga, Latvia, June 1, 2019. Photograph by Lauris Aizupietis. Courtesy of Nao Bustamante.

Nao Bustamante performing Given Over to Want, Autentika (Sculpture Quadrennial Riga), No New Idols performance festival, Riga, Latvia, June 1, 2019. Photograph by Lauris Aizupietis. Courtesy of Nao Bustamante.

While I am narrating an expansive brown commons that traverses the regime of the human, the politics that organize this thought experiment are primarily attached to the lives of human actants in larger social ensembles. I am drawn to the idea of a brown commons because it captures the way in which brown people’s very being is always a being-in-common. The brown commons is made of feelings, sounds, buildings, neighborhoods, environments, and the nonhuman organic life that might circulate in such an environment alongside humans, and the inorganic presences that life is very often so attached to. But first and foremost, I mean “brown” as in brown people in a very immediate way, in this sense, people who are rendered brown by their personal and familial participations in South-to-North migration patterns. I am also thinking of people who are brown by way of accents and linguistic orientations that convey a certain difference. I mean a brownness that is conferred by the ways in which one’s spatial coordinates are contested, and the ways in which one’s right to residency is challenged by those who make false claims to nativity.

Also, I think of brownness in relation to everyday customs and everyday styles of living that connote a sense of illegitimacy. Brown indexes a certain vulnerability to the violence of property, finance, and to capital’s overarching mechanisms of domination. Things are brown by law insofar as even those who can claim legal belonging are still increasingly vulnerable to profiling and other state practices of subordination. People are brown in their vulnerability to the contempt and scorn of xenophobes, racists, and a class of people who are accustomed to savagely imposing their will on others.

Nonhuman brownness is only partially knowable to us through the screen of human perception, but then every thing I am describing as being brown is only partially knowable. To think about brownness is to accept that it arrives at us, and that we attune to it only partially. Pieces resist knowing and being knowable. At best, we can be attuned to what brownness does in the world, what it performs, and the sense of the world that such performances engender. But we know that some humans are brown in that they feel differently, that things are brown in that they radiate a different kind of affect. Affect, as I am employing it in this project, is meant to address a sense of being-in-common as it is transmitted, across people, place, and spaces. Brown affect traverses the rhythmic spacing between those singularities that compose the plurality of a brown commons.

My use of “brown” is certainly an homage to the history of brown power in this country that was borne out of insurrectionist student movements. I do not mean brown in the way media pundits pronounce the browning of America in relation to national electoral politics. I am reaching back and invoking the sense of brown that was the Chicano walkouts of 1968, brown as in brown berets. Turning to the past in this particular fashion makes the point that the world is not becoming brown; rather, it has been brown. The brown power movement followed black power and was joined by red power, gay power, and other movements for liberation. They were movements that attempted to articulate a refusal of dominant logics and systems of thought, an insistence on thinking and doing otherwise. The brown power movement was intimately linked to modes of knowledge production and institutional practices that would ultimately congeal as ethnic, Latino, or Chicana/o studies.

As the case of book banning in Arizona shows us, the fact that the potential and force of brownness are intimately linked to the production of knowledge is not something that escapes the notice of the enemies of brown life. Draconian immigration laws that are springing up all over the country after the passage of Arizona’s sb 1070 have been shadowed by simultaneous legislation that has targeted the production of ethnic studies knowledge. While it should go without saying, it bears repeating that the violent attacks on ethnic studies and the knowledge it produces are also violent assaults on brown life. Fortunately, brown thought flows through the channels of what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten call the undercommons of the academy. While official curriculums and itineraries for learning are vulnerable to those who would drive them underground, brown practices of thought will—as they have always done—thrive in the realms of the intramural, the unofficial, and the fugitive.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Sense of Brown by José Esteban Muñoz, edited by Joshua Chambers-Letson and Tavia Nyong′o. Copyright Duke University Press, 2020.