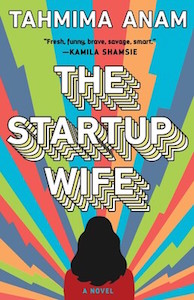

To Write a Comic Novel, I Had to Shed the Weight of Expectation (and Adopt a New Name)

Tahmima Anam on the Serious Business of Being Funny

Rose Lanam is the name of my alter ego. I conjured her up in order to write my new novel, The Startup Wife, my fourth book and my first comedy. Early on, as I was dreaming of this book, I realized I needed a new persona to write it. She needed to be of me, yet released from many of my preoccupations and anxieties as novelist. My first three novels were all set in Bangladesh, and they spanned a revolution, a turn towards religious fundamentalism, and the onset of climate change—very serious, very literary subjects, with very little scope for humor.

A few years ago, I started working at ROLI, a music tech startup founded by my husband. I’d been on the board since the beginning, advising him on corporate strategy and fundraising. After the birth of our daughter, I began working at the office almost every day, the baby in a sling. I wrote marketing copy and advised on hiring. I found it deeply satisfying to go to work, send emails, meet people, and consider my job for the day done.

It was during this time that the idea for a new novel came to me—a world-changing startup, a female founder, and a man—a sort of love triangle between two people and the company they start together.

I struggled to find the right voice for this novel. The weight of history was no longer on my shoulders, and the voices of real people no longer in my head. I had to make it all up, and in order to do that, I needed a new voice.

Although I hadn’t set out to become a particular kind of writer, I knew that those first three novels had been an act of extremely good behavior. I had done what the world had expected me to do—make an unfamiliar place more comprehensible. I had followed this up by writing numerous articles and opinion pieces about Bangladesh, bent on complicating peoples’ notions of a country that had fixed itself in the global public imagination through images of cyclones, starving children, and women in hijabs. I felt an ambassadorial responsibility to present an image of my home country that counteracted the media’s obsession with floods, famine, and fundamentalism.

I wanted to set this new book in another place I have called home: New York City. I am also an immigrant—although I was born in Bangladesh, I didn’t grow up there. I wanted to write a story about a person for whom a cultural or ethnic identity was one of the things that defined her, but not the only thing. The story wasn’t going to be about identity per se, but rather about how gender, race, and culture sit alongside other preoccupations and allegiances.

I felt an ambassadorial responsibility to present an image of my home country that counteracted the media’s obsession with floods, famine, and fundamentalism.

Could I do this? Could I write something that, say, a white person might want to write? The world of tech, of bro culture, of sexism in the workplace, a story about a marriage that isn’t arranged, a family who are Muslim but not practicing, and who don’t really talk that much about religion? What would that look like?

It is customary in Bangladesh to give one’s child a cute, often embarrassing nickname. Lucky for me, mine is Rose, not Pinky or Baby. When our children were born, my husband and I called them Lanam, a combination of his last name—Lamb—and mine—Anam. Together, we referred to ourselves as the Lanams. And when it came time to give my new novel an author, I decided on Rose Lanam. Rose Lanam was unburdened by history. She had no generational stories to tell—only her own. And she said fuck a lot.

I needed Rose Lanam to write this story. When I imagined her, I thought of a person who shed the weight of expectation like a heavy coat at the first sign of spring. She didn’t feel personally injured when a journalist asked her repeatedly what she thought of the hijab, not believing she had never been pressured to wear one herself. She didn’t feel it necessary to apologize for a dictatorial regime, or to praise the progress being made in women’s education in a country where child marriage was still a common practice. She had things to say about New York, Silicon Valley, and startup culture. Her politics occurred on a different stage.

In tech-speak, the word disrupt is haloed. Startup founders think they can disrupt everything, from the way we communicate with our loved ones to the way we order a pizza. They want to take us to the moon and have us sit in the back of driverless cars. But what they don’t ever try to do is disrupt the order of things, the way in which male founders are worshipped as the harbingers of transformational change. Rose Lanam is angry about this—she is angry about a lot of things. But she is also very funny, and she writes about vibrators and hemp milkshakes and pickles being the new superfood.

I have only recently become funny. I used to spend most of my energy trying to get people to take me seriously. As a short Asian woman who often got called cute (thank you, middle age, for banishing that particular label), I went to great lengths to be taken seriously. I did a PhD when I had no intention of becoming an academic. Everything from the way I dressed to my name-dropping of post-structuralist philosophers was aimed at signaling how not unserious I was.

My sense of humor coincided with a strengthening of my bonds with my female friends. As we got older and faced marriages, miscarriages, mothering, triumphs and disappointments in our careers, I found myself opening up to the power of laughter, and realizing what a transformative, radical act it might be to bring that to my writing. At first, I only dared bring out my inner comedian in WhatsApp messages to my friends. My jokes got dirtier, funnier, and more irreverent. Then I dipped my toe in the water and tried, with great trepidation, to write a comic novel.

I have only recently become funny. I used to spend most of my energy trying to get people to take me seriously.

As it turns out, The Startup Wife came to me almost fully formed, and the voice of the narrator was my voice—not one that I had inherited from anyone else, just mine, a person who had grown up, as I did, in the West, but whose parents were writers and social activists, who sang Tagore songs in the living room at every possible occasion. Asha Ray’s voice was uncensored, biting, and sometimes quite funny. She said fuck a lot.

And yet, when it came time to send the novel out for submission, I balked. I asked my agent to submit it under Rose Lanam’s name. I remember the look on her face when I told her—she never gives anything away, but I saw her hesitate before she said of course, yes, she would.

I know why I wanted to hide behind Rose Lanam. I know that the things I worried about—not being taken seriously, of being called light, shallow, and possibly misguided—are real things that have happened to comedy writers, especially women. Our humor is taken as lightness, our romances called flippant rather than subversive. Add to that the expectation of a kind of literary seriousness demanded of POC authors, and you have a potent set of standards. And I knew those standards would be applied to me. Perhaps not overtly—no one would come out and say: stay in your lane, brown writer, and give me some dead bodies, a couple of mullahs, maybe a child bride or two. But they would think it, despite themselves. That’s how the wheels of patriarchy turn.

In the end, it’s taken a crew of women—my cavalry, I like to think of them—to persuade me to bid adieu to Rose Lanam and put my real name on the cover of this book. My British editor, Ellah Allfrey, herself one of the only Black female editors in the UK, sat me down one afternoon and explained the ties between my earlier novels and this one, how I had always been preoccupied with women finding their voices, and that Asha was just a younger, more cosmopolitan character who faced some of the same challenges as those other protagonists. My American editor, Kara, who kept telling me that the book was as serious as it was funny, and others who read multiple drafts and chided me for saying it was just a romcom. There’s no such thing as just a romcom. Romance, humor, love, satire, social commentary—these are the things that women often interweave in their observations about the world.

A part of me still believes it isn’t possible to be a brown writer and also be funny and also be taken seriously. But I’ve taken the leap and put my name on the cover of this book. Because it is my name, as a very serious writer once put it. I cannot have another.

__________________________________________________

Tahmima Anam’s The Startup Wife is available now via Scribner.

Tahmima Anam

Tahmima Anam is the recipient of a Commonwealth Writers Prize, an O. Henry Prize, and has been named one of Granta’s Best Young British Novelists. She was a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times and was recently elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Born in Dhaka, Bangladesh, she was educated at Mount Holyoke College and Harvard University and now lives in London where she is on the board of ROLI, a music tech company founded by her husband.