To Sit Beside Boris Fishman on an Airplane is to Behold the Riches of Russian Cooking

On the Soviet Union, Scarcity, and Satisfaction

I’m dark-complexioned enough that people in first class—since 9/11, anyway—always look a second too long. I used to make myself shave before flights, but even if my ancestral darkness wasn’t bristling from my jaw, I would try, as I walked the aisle, to drop from my eyes the look of sullen intensity that was my default in New York. I wouldn’t go so far as to smile solicitously—that seemed like the kind of deflection a true foreign ill-doer would resort to. I would keep my eyes on the lumbering flier before me—just another passenger, patiently enduring.

Then I would walk the gauntlet of economy, now up to six staring faces per row. (I fantasized about first class for different reasons than legroom—fewer seats to reassure.) Most people want a higher-up row to get out of the airplane sooner; I did so I had fewer rows to placate. In the Soviet Union, my parents and grandparents had managed this complex matter of what others would think. In America, my elders constrained by their accents and fear, the job became mine: I stood to gain the most from the things Americans had power to give me, or not take away.

When I reached my seat, though, my attempts at passing had to come to an end. Out came the large Ziploc with the tinfoil bundles, big as bombs. The length of the flight didn’t matter. A flying day meant not knowing when the next good meal would arrive, and that meant a large pack of tinfoil bundles. I was mortified to reveal myself as the foreigner after all, but that foreigner would not allow me to pay more to eat less well at the airport concessions. Or up in the air: nine dollars for the Beef Up, or Perk Up, or Pump Up boxes, with their baffling combinations of the wholesome and processed, which reminded me of Russian people who consummated gluttonous meals with fruit because, look, they were health conscious eaters.

No, I brought my own food. I brought pieces of lightly fried whiting. Chicken schnitzels in an egg batter. Tomatoes, which I ate like apples. Fried cauliflower. Pickled garlic. Marinated peppers, though these could be leaky. Sliced lox. Salami. If plain old sandwiches, then with spiced kebabs where your turkey would be. Soft fruit bruises easily, but what better inter-meal snacks than peaches and plums? (You needed inter-meal snacks, just in case.)

It wasn’t only the money. A dime would have been too dear for the thing my seatmate was holding. How did Sbarro manage to make her pizza, black suns of pepperoni moated by a permafrost of white cheese, so smell-free? That arid iceberg, asiago, and turkey salad, watered by a cry-worthy ejaculation of chemical balsamic—its scentlessness I could understand. But pizza? That obese crust, made well, could have made the entire plane groan with longing.

One of the few things that seem to make Americans even more uncomfortable than being very close to each other for six hours in cramped quarters is when the next person over keeps pulling tinfoil bundles smelling sharply of garlic out of his rucksack. (I was kicked out of a bed once for radiating too much garlic under the covers. It was my father’s fault, I tried to explain—in America he had converted to saltless cooking, and now garlic was his one-to-one substitute; I had just had dinner with my parents. “Downstairs,” she commanded.) With the extra peripheral vision that is a kind of evolutionary adaptation for refugees, persecuted people, and immigrants, I would sense, on the plane, sideways glances of savage, disturbed curiosity. Sometimes I swiveled and committed the unpardonable sin of gazing directly at my neighbor, whereupon her eyes broadened, her forehead rose, and the rictus of a stunned smile overtook her agony.

Sometimes we ate raw onions like apples, too, I wanted to tell her. Sometimes, the tinfoil held shredded chicken petrified in aspic. A fish head to suck on! I was filled with shame and hateful glee: everything I was feeling turned out at the person next to me.

I was the one with an uncut cow’s tongue uncoiling in the refrigerator of his undergraduate quad, my roommates’ Gatorades and half-finished pad Thai keeping a nervous distance. I sliced it thinly, and down it went with horseradish and cold vodka like the worry of a long day sloughing off, those little dots of fat between the cold meat like garlic roasted to paste.

How did Sbarro manage to make her pizza, black suns of pepperoni moated by a permafrost of white cheese, so smell-free?

I am the one who fried liver. Who brought his own lunch in an old Tupperware to his cubicle in the Condé Nast Building; who accidentally warmed it too long, and now the scent of buckwheat, stewed chicken, and carrots hung like radiation over the floor, few of whose inhabitants brought lunch from home, fewer of whom were careless enough to heat it for too long if they did, and none of whom brought a scent bomb in the first place. Fifteen floors below, the storks who staffed the fashion magazines grazed on greens in the Frank Gehry cafeteria.

I was the one who ate mashed potatoes and frankfurters for breakfast. Who ate a sandwich for breakfast. Strange? But Americans ate cereal for dinner. Americans ate cereal, period, that oddment. They had a whole thing called “breakfast for dinner.” And the only reason they were right and I was wrong was that it was their country.

The problem with my desire to pass for native was that everything in the tinfoil was so fucking good. When the world thinks of Soviet food, it thinks of all the wrong things. Though it was due to incompetence rather than ideology, we were local, seasonal, and organic long before Chez Panisse opened its doors. You just had to have it in a home instead of a restaurant, like British cooking after the war, as Orwell wrote. For me, the food also had cooked into it the memory of my grandmother’s famine; my grandfather’s blackmarketeering to get us the “deficit” goods that, in his view, we deserved no less than the political VIPs; all the family arguments that paused while we filled our mouths and our eyes rolled back in our heads. Food was so valuable that it was a kind of currency—and it was how you showed love. If, as a person on the cusp of 30, I wished to find sanity, I had to figure out how to temper this hunger without losing hold of what fed it, how to retain a connection to my past without being consumed by its poison.

*

There’s nothing surprising about the idea that trauma—the aftereffects of being dehumanized and slaughtered, of lives made of terror even in peacetime—travels from one generation to another, not least because, if undealt with, it mutates, so that you grapple with not only your grandmother’s torment but what that torment did to your mother. All the same, it rattles you to learn, after devouring your own food year after year—a free country, sunlight outside, friends waiting, homework done—about the way your grandmother fell upon her first loaf all those years ago, like an animal. Nothing’s changed. Not even the way her proxies, themselves once victims of her pushing, push food at you even after you manage to summon, from somewhere, a modicum of brief self-control at the table on Avenue P. You scorn them for not managing to let go of three and six decades of grim lessons from that place, but have you managed much more despite leaving as a child? At least you’re trying.

In Chekhov’s letters—he was alone among the 19th-century Russian literary greats in having been born into the peasant class, with its servility and self-abnegation (his grandfather was a serf, Russia’s version of the feudally bonded)—you read: To be a writer, “you need . . . a sense of personal freedom. . . . Try writing a story about how a young man, the son of a serf . . . brought up venerating rank, kissing the hands of priests, worshiping the ideas of others, thankful for every crust of bread . . . hypocritical toward God and man with no cause beyond an awareness of his own insignificance—write about how this young man squeezes the slave out of himself drop by drop.” You have to admit that you don’t know how to write that story.

He wrote the letter at 29—your age in 2008 as you cross West Ninth Street and your grandfather’s apartment building finally appears before you, the ornamental patterning of its straw colored brick giving way to the usual south Brooklyn vestibule of cracked mirrors and peeling paint in almost-matched colors. You know what’s upstairs: polenta with sheep’s milk feta and wild mushrooms, pickled watermelon, eggplant “caviar,” rib tips with pickled cabbage, sorrel borshch, Oksana’s wafer torte with condensed milk and rum extract.

Once again, you have sworn to yourself: You will go slowly. You will eat half—no, a quarter!—of what’s shoved before you. You will leave feeling chaste, clean, ascetic, reduced. There is perhaps as little reason to count on this as there has been for the past hundred visits. As little reason as to hope that this will be the day when your conversation with your family will finally end in understanding instead of the opposite. Hope dies last, though. Was it not also Chekhov who wrote “The Siren,” a seven-page ode to food in the Russian mouth—“Good Lord! and what about duck? If you take a duckling, one that has had a taste of the ice during the first frost, and roast it, and be sure to put the potatoes, cut small, of course, in the dripping-pan too, so that they get browned to a turn and soaked with duck fat and . . .”

You come from a people who eat.

__________________________________

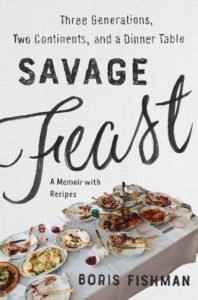

From the book Savage Feast by Boris Fishman. Copyright © 2019 by Boris Fishman. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Boris Fishman

Boris Fishman was born in the former Soviet Union and immigrated to the United States in 1988 at nine. He is the author of A Replacement Life and Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo (HarperCollins), both New York Times Notable Books of the Year. He has won the Sophie Brody Medal from the American Library Association and the VCU Cabell First Novelist Award. His journalism, essays, and criticism have appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine and Book Review, The Guardian, Travel & Leisure, New York Magazine, and many other publications.