The Time Cubes kiosk appeared in the main hall about a month before Christmas. Alice joined the crowd gathered around the vendor demonstrating the toys. Sandwiched between his open palms, he held a clear acrylic box, about a foot tall, a foot wide, and a foot deep, with a knob on one side that resembled an old-fashioned dimmer switch. The box contained a spindly green plant with heart-shaped leaves, planted in a glass jar. Behind him, on the shelves of the kiosk, lay a dozen identical boxes.

The salesman slowly spun the knob on the box in his hands, turning it toward himself. The leaves, previously still, at first undulated in an unseen wind. Then they began to shrink. At their smallest, they gathered at the stem and folded together like the pages of a book, curled back into buds. The central stalk receded until the entire plant had vanished into the soil.

He reversed course, turning the knob the other way. Within the box, the show proceeded in the proper order: a fresh shoot appearing in the jar of dirt, the plant growing and sprouting.

Until—unnervingly—he turned the knob past its original starting point. The plant expanded until it overgrew its container. Tendrils curved and wrapped where they hit the walls, and leaves pushed up against the transparent plastic like faces, fogging up the surface. The plant reached a glorious, full-crested peak, a jungle of one.

Then, choked, the leaves began to wilt and droop, shriveling to ribbons. The stalk tilted unsteadily in one direction, hunched over as though humbled. Eventually, bare brown wires hung over the edges of the jar like stringy human hair.

Alice clapped along with a few others, an uncertain smattering of applause that disappeared in the high ceilings of the main hall that smothered all sound. The toy seller turned the knob back and forth casually now, resurrecting and killing the plant, making it bigger and smaller, whipping it between full-grown and a seedling, a mere idea in the dark earth. As the knob spun rapidly, another effect became more noticeable: the box was lit up inside, by no obvious fixture—no visible bulbs or wiring—and the light flickered and strobed almost imperceptibly, similar to Alice’s vision when she was so exhausted that her eyelids twitched.

“Who wants to buy?”

The adults hesitated, a few children started to beg. The price was high, on par with a new, high-end smartphone. A lot to pay for an educational lifecycle toy that would likely end up forgotten in a toy chest by New Year’s. But they itched to take a Time Cube apart, to smash it open and see how it worked. If it was a holograph, it was better than any holographic technology Alice had ever seen, better than the porn, the billboards, the concerts, the holo-phones that had appeared in commercials as prototypes in development but had yet to materialize in stores. The plant looked real and substantial from every angle, and there was nowhere in the borderless box to hide a projector. Without the gaudy, backlit sign—Time Cubes!—one would assume the kiosk sold terrariums.

“Okay,” the toy seller said. “I see you’re not convinced.” From below the counter, he pulled out another clear plastic cube. “This is the slightly more expensive model,” he said.

At first, it was hard to see what was inside. It seemed like just more plants, a couple of hand-sized ferns, a thin layer of muddy water at the bottom with a branch laid across. Eventually, Alice registered movement—the pulsing under-chin of a bulbous, nearly spherical frog, black leopard spots across his green back.

The vendor wiggled his fingers and eyebrows, stuck the tip of his tongue out in pantomime of concentration. None of the children laughed.

He turned the knob backward. The frog began to twitch and wander through the cramped space, always reversing, his back legs stepping before the front, pausing at intervals. The back end of the frog winnowed into a tail as he slimmed down, as his dark, opaque flesh lightened to brown lace. At the point where he resembled a four-legged fish, he leapt onto the wall of the box facing the audience. Affixed there, he shrank to a black blotch, the distinctive ink-drop of a tadpole, which then slid down the wall until it came to rest in the puddle at the bottom, a black spot in a gooey bubble, and here the knob clicked as it hit its end—that was as far as it could turn. They would not see the frog’s parents materialize out of the air.

As the vendor turned the knob in the other direction, he sped through the stages they had just seen, as though bored. Egg to tadpole to froglet to frog, fascinating but familiar from any number of nature shows. When the adult frog was back in his sedentary position on the branch, Alice saw a woman near the front cover her mouth with one hand, and someone else started applauding again, a little frantically, trying to stop the demonstration here. Alice and the rest of the crowd did not join in, did not clap. They leaned in, pitching forward and rising up, shoulders expanding away from their waists, taking a deep, collective breath.

The frog didn’t age in any obvious way, and he moved less in adulthood, his stillness making the flickering of the light more apparent. Abruptly, in one motion, his legs splayed out underneath him, as though he were crushed by an invisible fist from above. A frenzy of movement followed, a staticky shadow cast over the frog and the murky puddle surrounding him, replacing his eyes with empty holes, deflating the body while leaving the skin relatively intact: a frog-skin rug, a silhouette. At last, the shadow dispersed, and the wild, crimped angles of the frog’s skeleton were all that remained. The knob clicked with an air of finality.

One little boy, his eyes crushed to slits between his high cheeks and low forehead, said flatly, seemingly to no one in particular, “You have to buy me that. You have to.”

Alice’s Depressive Specialist said they were living in a paradise, and Alice had to agree, in the sense that the recent past was worse, the future would almost certainly be worse, and the present was worse for most other people, living elsewhere. She said that Alice’s thoughts and fears were extremely common, as Depressives were now a plurality, exceeding any other categorization. She said this like it was supposed to be comforting.

Alice identified as a Depressive Insider, the latter designation meaning she did not leave the Mall. She lived on the seventy-fifth floor of the south tower and she worked as a lab tech on basement five of the east tower; her Depressive Specialist was two floors up on east basement two. Alice didn’t even go out onto the skybridges that connected the four towers anymore, preferring the tunnels and indoor connectors. The skybridges were always extremely crowded, for one thing, everyone pressed to the gaps in the open fencing, staring at the dim red medallion of sun or moon. In the winter, the air was hot and damp, and the rest of the year, an irritating dust blew through, tearing into your eyes and throat—sometimes a color like powdered rust that stained your clothes, sometimes a reeking sulfurous yellow, sometimes sparkling and colorless like crushed diamonds.

The fencing prevented jumpers, so there was really no appeal for Alice.

Alice’s Depressive Specialist suggested she try dating or casual sex as a way to lift her mood. She recommended location-based apps; proximity would limit the energy and motivation required, and if she turned on the path-matching feature, she would likely be matched with other Insiders. “But base your search primarily on physical attractiveness,” she said. “Just go for someone sexy.”

Like most other things on her phone, the dating apps were lulling and hypnotic. When she played with them, she forgot what she was supposed to be doing, what the goal was, comforted by the light of the screen and the swiping gestures, the same ones that had soothed her as an infant. She tried to look at people passing her in the Mall corridors, the people crammed in with her in the elevator, but their faces came apart the longer she stared at them. Their features clustered in new ways, piles of eyeballs and noses and mouths that she didn’t know how to judge as sexy/not-sexy.

Through December, when Alice wasn’t working or with her Depressive Specialist, she usually found herself back at the Time Cube kiosk, watching the seller’s demonstration. The plant and the frog, alive and then dead and then alive. To her surprise, it didn’t seem like they sold well, despite the large crowd stopping up the flow of pedestrian traffic in the main hall. She would have bought one if she could have afforded it.

The vendor was about her age, maybe slightly younger. He looked like someone who cared for his appearance tenderly, with small, vain touches, like grace notes on a sheet of music. His clothes were neatly pressed, his shoes shined, his skin uncommonly even and smooth—porcelain with a rosy glow under the eyes, bringing to mind a Renaissance portrait. And because she spent so much time watching him, his face and hands, with their magician flourishes and waggles, developed a comforting familiarity, like the faces of her lab mates and her dead parents in dreams. She could round all of this up to “sexy.”

On her day off, after the vendor pulled the rollaway walls down over his kiosk and locked it up at the end of the day, she followed him to the dining hall. He went to the one on the fourth floor of the west tower that Alice rarely visited. She preferred basement six north, where the food stalls were identical, save the signs indicating the shapes and flavors of the patties: steel countertops between evenly spaced white laminate pillars, hundreds of identical seats at identical tables in a grid pattern in the center, the lighting soft but bright—sterile and undemanding, like her lab. West four, instead, traded in nostalgia. The “taco” stand served out of a fake food truck, and bar seating was sectioned off and clustered around the other stalls, mimicking the feel of restaurants, a dead institution. It made everything taste a little worse, coated as it was in longing, like the dust of the skybridges.

She got behind him in line at the “noodle” stall. Once she had her bowl, she made a show of looking for a seat before asking if she could take the one beside him. In Alice’s experience, most people in the Mall disliked being interrupted from their bubbles of solitude or chosen company, even accidentally. She once asked the “muffin” vendor in basement six north what his favorite muffin was, and the deviation from script rattled his plastered smile into something like hatred.

But the Time Cube vendor looked terribly pleased, like he’d been expecting her. He had a wide mouth and thin lips that gave him a wolfish aspect when he grinned, and his hair was shiny and stiff with product. Alice had never cold-propositioned a stranger for sex, and she didn’t know how to make the con-versation move on from how much he enjoyed his nutritional patty, shredded into long, noodle-like strips. It turned out to be easy. She abruptly interrupted to ask if he had plans for the evening, and he did not.

Afterward, she tried to remember why her Depressive Specialist had recommended this. Had it lifted her mood? Alice had been demanding and straightforward; the Time Cube vendor was agreeable but self-involved, falling asleep after coming so easily and immediately it was like he’d been knocked out with a frying pan.

She got out of bed and wandered into the hall of his unit. He lived on west thirty. The lower floors of the west tower were older, the floor plans slightly larger but the ceilings lower, and because the mold-resistant coating was slathered on top of instead of woven into surfaces, the walls where her fingers brushed were grimy and damp. She’d spent so much time in her unit and identical ones that the small differences in square footage and height felt disorienting, the rooms elongated in perspective like a tunnel.

Incredibly, he had a second bedroom but no roommate, a fact that must have involved fraud or recent death. She thought the door to the second bedroom was locked, but she instinctively kept turning the handle and pushing the door with her shoulder, and discovered the lock was broken. With a pop, the door jerked suddenly open, the handle still stuck in the locked position, the faux wood juddering.

She closed the door behind her, forcing the handle a second time. She’d found what she was looking for, almost. The room was stuffed with machinery and tools, circuit boards, sheets of thick, uncut plastic. Workbenches lined three walls. A cylindrical machine, about eight feet long, took up most of the floor space, its top and bottom halves hinged together—a manufacturing mold for the cubes, perhaps.

Unfinished cubes were scattered on the benches and the floor, open-topped and missing their knobs. One was filled with gray ash. Another contained the bones of a bird lying on its side, pulled apart and picked nearly clean, just a few tufts of molding feathers along the back of one hip bone. Another had a rodent skeleton in a vivarium of living grass, a wraparound whip of bleached spine, skull, and front paws, the back legs missing. The sight of these tiny corpses, combined with the smell of sex clinging to Alice’s skin, made her gut flop inside her like a swallowed fish. She could see why he stuck to selling the frog and plant versions.

She hadn’t found a single finished Time Cube, a knob she could reel. Disappointment soured her tongue. In her search, she pulled out a latched case tucked under a workbench and flipped it open.

The case held an old, basic tablet computer, the kind commonly configured for single-purpose use—as a cash register, as a map, as a photo frame that rotated through pictures. It came to life in her hands and revealed itself as the latter. The photos were of an older man who closely resembled the Time Cube vendor, maybe his father or much older brother, all taken in casinos, strip clubs, concerts, raves, all dimly and colorfully lit. Drink glasses held aloft, attractive younger women surrounding him in bar booths and hot tubs. Fun as defined by an old beer commercial, or a certain kind of thirteen-year-old boy. As she scrolled, the teen-boy-at-heart developed liver spots on his bald pate, and bands of muscle and skin hung looser from the shrinking stem of his neck. All the background faces were smeared with alcohol, half-lidded or out of focus, but his eyes glowed with sober, consistent, childlike joy. He loved this life.

No weariness accompanied his aging. Alice wondered who he was to the Time Cube vendor, why this photo reel would be in his workshop. If his father was his hero or cautionary tale, or nothing to him at all.

She put the case back. She lifted the heavy lid of the machine she’d assumed was a manufacturing press, and was surprised to find that it was almost completely hollow on the inside. All of the machinery was pressed against the inner walls to accommodate the defined, empty space—wires and tubes and, bizarrely, metal gears, which Alice had only ever seen in textbooks when she was in school. The hollow was ovular, human-sized. Alice had trouble seeing the machine as she had before.

The inside of the upper lid had the same rotating knob as the Time Cubes.

Alice understood right away. She felt magnetically drawn, as she had been to the suicide-proof fencing on the skybridges, once, even as her thoughts were slow to form in words, to unspool the implications. She pressed one palm against the edge of the hollow for leverage as she swung her leg up and over to climb inside. She had to awkwardly hold up the heavy lid with the other hand to keep it from slamming shut on top of her limbs prematurely.

He’d chosen to make these silly toy cubes when he had the most sought-after power on earth, the stuff of poetry and legendary kings. He probably had the sense to know that his real product would make him hunted, rather than rich. Maybe he could have advertised it as an antiaging treatment, become secret cosmetic doctor to the stars, but even that would require letting people in too close. Better to use it only on himself, in the pettiest and most obvious way possible: to stay young and beautiful.

She let the lid settle over her. It didn’t close completely—a thin edge of light was visible in the space between the two halves. She could hear herself breathing, and the ambient noise of the vendor’s apartment, almost identical to the noise in her apartment, the gurgles and shuffling and thuds that were in everyone’s walls, so heavily insulated from the outside and so thinly from one another.

She wondered what her Depressive Specialist would say. A healthy mind would want to turn the knob backward, hungry for more life, gasping for it, feeling the constriction of time like limited oxygen in a small room. A better person would grow philosophical. Maybe if she smashed open all the boxes, unraveled his machinery and ran the cords around the equator, she could spin the planet backward, go back far enough to save the world from itself.

But, Alice thought, she was as vain and self-obsessed as the Time Cube vendor, just in a different way. “Depressives are selfish,” her Specialist had said. “You’re selfish, and then you berate yourself for being selfish, which is just another way of focusing your attention on yourself.” Said in the same gentle, infuriatingly patient voice in which she said everything.

Alice turned the knob to the right. Forward.

She thought she’d be focused on her body aging, like the plant and the frog, that she’d be able to feel, say, her hair graying and her teeth falling out and her wrinkles deepening, her muscles slackening, pain blooming in her joints, her sight and hearing fading. Or that she would die quickly, reach the clicking end of the knob and be released, let out through the door she had been pounding on for so long, the hum of existence finally quiet.

She hadn’t wondered what the frog had been thinking, flying forward through his life, absorbing it all at once, the taste of every insect he would ever eat, everything those bulbous eyes would ever see. There was a rush that ruffled and stung like a strong wind. She hadn’t anticipated a lifetime of joy and sorrow, beauty and mundanity and horror, all compressed into seconds. Entire arcs of romance and friendship with people she hadn’t met yet, feeling the thrill of first connection at the same instant as their final betrayal. Her mouth kissed and her body entered and bruised thousands of times at once. Every Depressive nadir and reprieve, every greeting and goodbye, like being beaten across the face with a swinging door. Her nerves screamed, her spirit contorting through every action while her body lay still—except her fingers, still determinedly turning.

She heard, distantly, rustling elsewhere in the apartment. The Time Cube vendor opening the door to his bedroom. His footsteps pounding down the hall, his panicked voice incorrectly guessing her name. The broken lock popping free as he forced his way inside.

She turned the knob faster. Grief heaped upon her like dirt from a shovel, stacking and directionless. She mourned the loss of a beloved, as-yet-unknown person, simultaneously mourning the loss of dozens of others, a generation crumbling around her like pillars of salt. All of it spiraling around one emotion, one lesson, in tighter and tighter circles. That knowledge at the center—so near, almost within her grasp—kept her fingers turning, even as the Time Cube vendor tried to wrench the lid of the machine upward, as he kept shouting a name that wasn’t her name. She held fast to the knob, listening for the click.

__________________________________

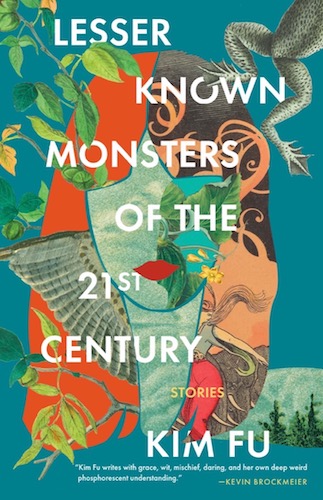

Excerpted from Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century: Stories by Kim Fu. Published with permission from Tin House. Copyright (c) 2022 by Kim Fu.