The Strangest Feeling in My Legs

DANIEL

Donegal, 2010

There is a man.

He’s standing on the back step, rolling a cigarette. The day is typically unstable, the garden lush and shining, the branches weighty with still-falling rain.

There is a man and the man is me.

I am at the back door, tobacco tin in hand, and I am watching something in the trees, a figure, standing at the perimeter of the garden, where the aspens crowd in at the fence. Another man.

He’s carrying a pair of binoculars and a camera.

A bird-watcher, I am telling myself as I pull the frail paper along my tongue, you get them in these parts. But at the same time I’m thinking, Really? Bird-watching, this far up the valley? I’m also thinking, Where is my daughter, the baby, my wife? How quickly could I reach them, if I needed to?

My heart cranks into high gear, thud-thudding against my ribs. I squint into the white sky. I am about to step out into the garden. I want the guy to know I’ve seen him, to see me seeing him. I want him to register my size, my former track-and-field-star physique (slackening and loosening a little, these days, admittedly). I want him to run the odds, me versus him, through his head. He’s not to know I’ve never been in a fight in my life and intend it to stay that way. I want him to feel what I used to feel before my father disciplined me: I am on to you, he would say, with a pointing finger, directed first at his chest, then mine.

I am on to you, I want to yell while I fumble to pocket my cigarette and lighter.

The guy is looking in the direction of the house. I see the tinder spark of sun on a lens and a movement of his arm that could be the brushing away of a hair across the forehead or the depression of a camera shutter.

Two things happen very fast. The dog—a whiskery, leggy, slightly arthritic wolfhound, usually given to sleeping by the stove—streaks out of the door, past my legs, and into the garden, emitting a volley of low barks, and a woman comes around the side of the house.

She has the baby on her back, she is wearing the kind of sou’wester hood usually sported by North Sea fishermen, and she is holding a shotgun.

She is also my wife.

The latter fact I still have trouble adjusting to, not only because the idea of this creature ever agreeing to marry me is highly improbable, but also because she pulls unexpected shit like this all the time.

“Jesus, honey,” I gasp, and I am momentarily distracted by how shrill my voice is. “Unmanly” doesn’t cover it. I sound as if I’m admonishing her for an ill-judged choice in soft furnishings or for wearing pumps that clash with her purse.

She ignores my high-pitched intervention—who can blame her?— and fires into the air. Once, twice.

If, like me, you’ve never heard a gun report at close range, let me tell you the noise is an ear-shattering explosion. Magnesium-hued lights go off inside your head; your ears ring with the three-bar high note of an aria; your sinuses fill with tar.

The sound ricochets off the side of the house, off the flank of the mountain, then back again: a huge aural tennis ball bouncing about the valley. I realize that while I’m ducking, cringing, covering my head, the strangest feeling in my legs the baby is strangely unmoved. He’s still sucking his thumb, head leaning against the spread of his mother’s hair. Almost as if he’s used to this. Almost as if he’s heard it all before.

I straighten up. I take my hands off my ears. Far away, a figure is sprinting through the undergrowth. My wife turns around. She cracks the gun in the crook of her arm. She whistles for the dog. “Ha,” she says to me before she vanishes back around the side of the house. “That’ll show him.”

My wife, I should tell you, is crazy. Not in a requiring-medication-and-wards-and-men-in-white-coats sense—although I sometimes wonder if there may have been times in her past—but in a subtle, more socially acceptable, less ostentatious way. She doesn’t think like other people. She believes that to pull a gun on someone lurking, in all likelihood entirely innocently, at our perimeter fence is not only permissible but indeed the right thing to do.

Here are the bare facts about the woman I married:

—She’s crazy, as I might have mentioned.

—She’s a recluse.

—She’s apparently willing to pull a gun on anyone threatening to uncover her hiding place.

I dart, insomuch as a man of my size can dart, through the house to catch her. I’m going to have this out with her. She can’t keep a gun in a house where there are small children. She just can’t. I’m repeating this to myself as I pass through the house, planning to begin my protestations with it. But as I come through the front door, it’s as if I’m entering another world. Instead of the gray drizzle at the back, a dazzling, primrose-tinted sun fills the front garden, which gleams and sparks as if hewn from jewels. My daughter is leaping over a rope that her mother is turning. My wife who, just a moment ago, was a dark, forbidding figure with a gun, a long gray coat, and a hat like Death’s hood, she has shucked off the sou’wester and transmogrified back to her usual incarnation. The baby is crawling on the grass, knees wet with rain, the bloom of an iris clutched in his fist, chattering to himself in a satisfied, guttural growl.

It’s as if I’ve stepped into another time frame entirely, as if I’m in one of those folktales where you think you’ve been asleep for an hour or so, but you wake to find you’ve been away a lifetime, that all your loved ones and everything you’ve ever known are dead and gone. Did I really just walk in from the other side of the house, or did I fall asleep for a hundred years?

I shake off this notion. The gun business needs to be dealt with right now. “Since when,” I demand, “do we own a firearm?”

My wife raises her head and meets my eye with a challenging, flinty look, the skipping rope coming to a stop in her hand. “We don’t,” she says. “It’s mine.”

A typical parry from her. She appears to answer the question without answering it at all. She picks on the element that isn’t the subject of the question. The essence of sidestepping.

I rally. I’ve had more than enough practice. “Since when do you own a firearm?”

She shrugs a shoulder, bare, I notice, and tanned to a soft gold, bisected by a thin white strap. I feel a momentary automatic mobilization deep inside my underwear—strange how this doesn’t change with age for men, that we’re all of us but a membrane away from our inner teenage selves—but I pull my attention back to the discussion. She’s not going to get away with this.

“Since now,” she says. “What’s a fire arm?” my daughter asks, splitting the word in two, her small, heart-shaped face tilted up to look at her mother.

“It’s an Americanism,” my wife says. “It means ‘gun.’ ”

“Oh, the gun,” says my sweet Marithe, six years old, equal parts pixie, angel, and sylph. She turns to me. “Father Christmas brought Donal a new one, so he said Maman could have his old one.”

This utterance renders me, for a moment, speechless. Donal is an ill-scented homunculus who farms the land farther down the valley. He—and his wife, I’d imagine—have what you might call a problem with anger management. Somewhat trigger-happy, Donal. He shoots everything on sight: squirrels, rabbits, foxes, hill walkers (just kidding).

“What is going on?” I say. “You’re keeping a firearm in the house and—”

“ ‘Gun,’ Daddy. Say ‘gun.’ ”

“—a gun, without telling me? Without discussing it with me? Don’t you see how dangerous that is? What if one of the children—”

My wife turns, her hem swishing through the wet grass. “Isn’t it nearly time to leave for your train?”

* * * *

I sit behind the wheel of the car, one hand on the ignition, the cigarette from earlier gripped between my lips. I am searching my pocket for an elusive lighter or box of matches. I’m determined to smoke this cigarette at some point, before the strike of noon. I limit myself to three a day and, boy, do I need them.

I am also shouting at the top of my voice. There’s something about living in the middle of nowhere that invites this indulgence.

“Come on!” I yell, secretly admiring the volume I can produce, the way it echoes around the mountain’s lower reaches. “I’m going to miss my train!”

Marithe appears unaware of the commotion, which is commendable in one way and irksome in another. She has a tennis ball or similar in a sock and is standing with her back against the wall of the house, counting (in Irish, I notice, with a ripple of surprise). With each number—aon, dó, trí, ceathair—she thwacks the socked ball off the wall, dangerously close to her body. I watch while shouting some more: she’s pretty good at it. I catch myself wondering where she learned this game. Not to mention the Irish. She is homeschooled by her mother, as was her elder brother, until he rebelled and enlisted himself (with my clandestine help) at a boarding school in England.

My schedule is such that I often spend the workweek in Belfast, coming back to this corner of Donegal on weekends. I teach a course in linguistics at the university, coaching undergraduates to break up what they hear around them, to question the way sentences are constructed, the manner in which words are used, and to make a stab at guessing why. I’ve always concentrated my research on the way languages evolve. I’m not one of those traditionalists who lament and breast-beat about how grammar is deteriorating, how semantic standards are slipping. No, I like to embrace the idea of change.

Because of this, within the extremely narrow field of academic linguistics, I retain an aura of the maverick. Not much of an accolade, but there you are. If you’ve ever listened to a radio program about neologisms or grammatical shifts or the way teenagers usurp and appropriate terms for their own, often subversive use, it probably was me who was wheeled in to say that change is good, elasticity is to be embraced.

I once said this in passing to my mother-in-law and she held me for a moment in her imperious, mascaraed gaze and said, in her flawless Parisian English, “Ah, but no, I would not have heard you because I always switch off the radio if I hear an American. I simply cannot listen to that accent.”

Accent aside, I am due, in several hours, to deliver a lecture on pidgins and creoles, based around a single sentence. If I miss this train, there isn’t another that will get me there in time. There will be no lecture, no pidgins, no creoles, but instead a group of undergraduates who will never be enlightened as to the fascinating, complex linguistic genealogy of the sentence: “Him thief she mango.”

I am also, after the lecture, due to catch a flight to the States. After extensive transatlantic pressure from my sisters, and against my better judgment, I am going over for my father’s ninetieth birthday party. What kind of a party may be had at the age of ninety remains to be seen, but I’m anticipating a lot of paper plates, potato salad, tepid beer, and everyone trying to ignore the fact that the celebrant himself is scowling and grumbling in a corner. My sisters have been saying that our father could shuffle off his mortal coil at any time, and they know that he and I haven’t always seen eye to eye (to put it mildly), but if I don’t come soon I will regret it for the rest of my life, blah, blah. Listen, I tell them, the man walks two miles every day, eats enough pulled pork to depopulate New York State of pigs, and he certainly doesn’t sound infirm if you get him on the phone: never does he find himself at a loss when pointing out my shortcomings and misjudgments. Plus, with regard to his much-vaunted potential death, if you ask me, the man never had a pulse in the first place.

This visit—my first in over five years—is not, I am telling myself, the reason for my stress, the explanation for my brain-bending craving for nicotine or for the jittery twitch of my eyelid as I sit waiting. It has nothing to do with it, nothing at all. I’m just a little edgy today. That’s all. I will go to Brooklyn, I will visit with the old man, I will make nice, I will go to the party, I will give him the birthday gift my wife has purchased and wrapped, I will chat with my nieces and nephews, I will stick it out for the requisite number of days—and then I will get the hell out.

I crack open the car door and scream “Where are you? I’m going to miss my lecture” into the damp air, then spy a crumpled book of matches in the footwell of the car. I disappear down for it, like a pearl diver, resurfacing triumphant with it in my hand.

At this moment, my wife yanks open the door and commences strapping the baby into his car seat.

I exhale as I strike a match. If we leave now, we should make it.

Marithe scrambles into her place; the dog squeezes in, then over the seat and into the back; the passenger door opens, and my wife slides into the car. She is, I notice, wearing a pair of man’s trousers, cinched around the waist with what looks suspiciously like one of my silk neckties. Over the top of this is a coat that I know for a fact once cost more than my monthly salary—a great ugly thing of leather and tweed, straps and loops—and on her head is a rabbit-fur hat with elaborate earflaps. Another gift from Donal? I want to inquire, but don’t because Marithe is in the car.

“Phew,” my wife says. “It’s filthy out there.”

Into the backseat, she tosses a wicker basket, a burlap sack, something that looks like a brass candelabra, and, finally, an ancient, tarnished egg whisk.

I say nothing.

I slide the car into first gear and let off the brake, with a perverse feeling of accomplishment, as if getting my family to leave ten minutes late is a major achievement, and I draw the first smoke of the day down into my lungs, where it curls up like a cat.

My wife reaches out, plucks the cigarette from my lips, and stubs it out.

“Hey!” I protest.

“Not with the children in the car,” she says, tipping her head toward the backseat.

I am about to pick up the argument and run with it—I have a whole defense that questions the relative dangers to minors of firearms and cigarettes—but my wife turns her face toward mine, fixes me with her jade stare, and gives me a smile of such tenderness and intimacy that the words of my prepared speech drain away, like water down a plughole.

She puts her hand on my leg, just within the bounds of decency, and whispers, “I’ll miss you.”

As a linguist, it’s a revelation to me the number of ways two adults can find to discuss sex without small children having the faintest idea what is being said. It is a testament to, a celebration of, semantic adaptability. My wife smiling like this and saying, I’ll miss you, translates in essence to: I’m not going to be getting any while you’re away but as soon as you’re back I’m going to lead you into the bedroom and remove all your clothes and get down to it. Me clearing my throat and replying “I’ll miss you too” says, Yep, I’ll be looking forward to that moment all week.

“Are you feeling OK about the trip?”

“To Brooklyn?” I say, in an attempt to sound casual, but the words come out slightly strangled.

“To your dad,” she clarifies.

“Oh,” I say, circling my hand in the air. “Yeah. It’ll be fine. He’s . . . er, it’ll be fine. It’s not for long, is it?”

“Well,” she begins, “I think that he—”

Marithe might be picking up on something because suddenly she shouts, a little louder than necessary, “Gate! Gate, Maman!”

I stop the car. My wife snaps off her seat belt, shoves open her door, steps out, and slams the door, exiting the small rhombus of the rain-glazed passenger window. A moment later, she reappears in the panorama of the windshield: she is walking away from the car. This triggers some preverbal synapse in the baby: his neurology tells him that the sight of his mother’s retreating back is bad news, that she may never return, that he will be left here to perish, that the company of his somewhat-scatterbrained and only occasionally present father is not sufficient to ensure his survival (he has a point). He lets out a howl of despair, a signal to the mothership: Abort mission, request immediate return.

“Calvin,” I say, using the time to retrieve my cigarette from the back of the dashboard, “have a little faith.”

My wife is unlatching a gate and swinging it open. I ease up on the clutch, down on the gas, and the car slides through the gate, my wife shutting it after us.

There are, I should explain, twelve gates between the house and the road. Twelve. That’s one whole dozen times she’ll have to get out of the car, open and shut the damn things, then get back in again. The road is a half mile away, as the crow flies, but to get there takes a small age. And if you’re doing it alone, the whole thing is a laborious toil, usually in the rain. There are times when I need something from the village—a pint of milk, toothpaste, the normal run of household requirements—and rise from my chair, only to realize that I’ll have to open no fewer than twenty-four gates, in a round-trip, and I sink back down, thinking, hell, who needs to clean their teeth?

The word “remote” doesn’t even come close to describing the house. It’s in one of the least-populated valleys of Ireland, at an altitude even the sheep eschew, let alone the people. And my wife chooses to live in the highest, most distant corner of this place, reached only by a track that passes through numerous livestock fences. Hence the gates. To get here, you have to really want to get here.

The car door is wrenched open and my wife slides back into the passenger seat. Eleven more to go. The baby bursts into tears of relief. Marithe yells, “One! One gate! One, Daddy, that’s one!” She is alone in her love of the Gates. The dashboard immediately starts up a hysterical bleeping, signaling that my wife needs to fasten her seat belt. I should warn you that she won’t. The bleeping and flashing will continue until we get to the road. It’s a bone of contention in our marriage: I think the hassle of fastening and unfastening the seat belt is outweighed by the cessation of that infernal noise; she disagrees.

“So, your dad,” my wife continues. She has, among her many other talents, an amazing ability to remember and pick up half-finished conversations. “I really think—”

“Can you not just put the seat belt on?” I snap. I can’t help it. I have a low threshold for repetitive electronic noises.

She turns her head with infinite, luxurious slowness to look at me. “I beg your pardon?” she says.

“The seat belt. Can’t you just this once—”

I am silenced by another gate, which looms out of the mist. She gets out, she walks toward the gate, the baby cries, Marithé yells out a number, et cetera, et cetera. By the penultimate gate, there is a dull pressure in my temples that threatens to blossom into persistent dents of pain.

As my wife returns to the car, the radio fizzes, subsides, crackles into life. We keep it permanently switched on because reception is mostly a notion in these parts, and any snatch of music or dialogue is greeted with cheers.

“Oh, Brendan! Brendan!” an actress in a studio somewhere earnestly emotes. “Be careful!” The connection dissolves in a crackle of static.

“Oh, Brendan, Brendan!” Marithe shrieks, in delight, drumming her feet into the back of my seat. The baby, quick to catch the general mood, gives a crowing inhale, gripping the edges of his chair, and the sun chooses that moment to make an unexpected appearance. Ireland looks green and pleasant and blessed as we skim along the track, splashing through puddles, toward the final gate.

My wife and Marithe are debating what Brendan may have needed to be careful of, the baby is repeating an n sound, and I am thinking it’s early for him to be using his palate in such a way as I idly turn the dial to see what else we can find.

I pull up at the last and final gate. A Glaswegian accent filters through the white noise, filling the car, speaking in the self-consciously serious tones of the newscaster. There is some geographical blip that means we can, on occasion, pick up the Scottish news. Something about an upcoming local election, a politician caught speeding, a school without textbooks. I twirl the dial through waves of nothingness, searching for speech, panning for a human voice.

My wife gets out of the car; she walks toward the gate. I watch the breeze snatch and toy with hanks of her hair, the upright, ballet dancer’s gait of her, her hand in its half mitten as she grips the gate lock.

The radio aerial strains and picks up a female voice: calm but hesitant. It’s something about gender and the workplace, one of those issue-led magazine programs you get in the middle of the morning on the BBC. A West Country octogenarian is speaking about being one of the first women employed as an engineer, and I’m about to turn the dial farther, as it’s the kind of thing my wife will be avid to hear and I am really in the mood for some decent music. Then a different voice comes out of the little perforated speakers near my knee: the dipping, vowel-lengthened accent of the educated English.

“And I thought to myself, my God,” the woman on the radio says, into my car, into the ears of my children, “this must be the glass ceiling I’ve heard so much about. Should it really be so hard to crack it with my cranium?”

These words produce within me a deep chime of recognition. Without warning, my mind is engaged with a series of flash cards: a cobbled pavement indistinct with fog, a bicycle chained to a railing, trees dense with the scent of pine, a giving pelt of fallen needles underfoot, a telephone receiver pressed to the soft cartilage of an ear.

I know that woman, I want to exclaim, I knew her. I almost turn and say this to the kids in the back: I knew that person, once. I am remembering the black cape thing she used to wear and her penchant for unwalkable shoes, weird, articulated jewelry, outdoor sex, when the voice fades out and the presenter comes on air to tell us that was Nicola Janks, speaking in the mid-1980s.

I slap my palm on the wheel. Nicola Janks, of all people. Never have I otherwise come across that surname. She remains the only Janks I ever knew. She had, I seem to recall, some crazy middle name, something Grecian or Roman that bespoke parents with mythological proclivities. What was it now? I am recalling, ruefully, that it’s no real surprise that things from that time might seem a little hazy, given the amount of—

And then I am thinking nothing. The presenter is intoning, in the straitened, delicate way that can mean only one thing, that Nicola Janks died not long after the interview was recorded.

My brain performs a series of jolts, like an engine about to stall. I look instinctively for my wife. She has swung the gate open and is waiting for me to drive through.

There is the sensation that a window somewhere has blown open or a single domino has fallen against another, causing a cascade. A tide has rushed forward, then pulled back out, and whatever was beneath it is altered forever.

I gaze back at my wife. She is holding the gate. She leans her weight against it so that it doesn’t blow back against the car. She is holding it, trusting that I will drive the car through, the car that contains her children, her offspring, her beloveds. Her hair fills with the Irish wind, like a sail. She is searching the windshield now for my face, wondering why I am not moving forward, but from where she is standing, the glass is opaque with the reflections of clouds. From where she is standing, I might not even be here at all.

* * * *

The train pulls over the border, in an easterly direction, in and out of rain showers. I sit with the newspaper my wife bought me rolled in my hand like a baton, as if I am on the brink of guiding an invisible orchestra through a symphony.

It’s been ten years since I did the reverse journey, on a pilgrimage of sorts. I’d never been to Ireland then: it had simply never occurred to me to come. I am not one of those Irish Americans coshed by a sense of Eiresatz nostalgia, filled with backward-looking whimsy about a country that our great-grandparents were forced out of in order to survive. Within my family I was alone in this: my sisters all wore Claddagh rings, went to St. Patrick’s Day parades, and gave their children names with tricky clusters of d’s and b’s.

I was working at Berkeley, somewhat uncomfortably, as part of the cognitive sciences department. My marriage had just ground to a halt: my wife had been having an affair with a colleague for years, it had transpired. This revelation had pushed me into a minor dalliance, which had in turn prompted my wife to sue for divorce. I was living in the apartment of a friend who was in Japan on a sabbatical; the cuckolding colleague had moved into the house from which I had so recently been ejected. My soon-to-be-ex-wife had morphed into a vengeful harpy who had decided I should pay her astronomic amounts of alimony in return for minimal contact with my kids. Week after week, she refused to honor the custody arrangement our lawyers had thrashed out. I was pouring my entire salary into fighting this; I was having ill-advised affairs with two different women, and preventing their discovery of each other was causing me undue complications and evasions.

In the middle of this brew, my grandmother died and, according to the surprising instructions in her will, was cremated. The usual familial disagreements ensued as to what we should do with her ashes. My aunt favored an urn, in particular an antique Chinese ginger jar she’d seen on sale; my father wanted to go ahead with a burial. An uncle put out the suggestion of a family plot; another was keen to go the way of some kind of woodland, tree-planting deal. It was a cousin who said, shouldn’t we put her with Grandpa?

We all looked at one another. It was the end of the wake: the priest had left; the guests were dwindling; the room was filled with crumpled napkins, crumbled cake, and wreaths of cigarette smoke. My dad and his siblings lowered their eyes.

The truth came out, as truths are meant to do at funerals: no one quite knew where Grandpa’s remains were. The story was that, years ago, he and Grandma had taken what everyone agreed was their first vacation, to Ireland. Grandpa had retired from the business, and they had never seen the country of their grandparents, all their friends had been, they had a little bit put by, and so on and so forth. Fill in for yourselves the usual reasons why people go on vacation.

They flew to Dublin. They saw the Ring of Kerry, then looked around Cork, the Dingle Peninsula. They saw the famous dolphin. For some reason—no one knew why—they ended up in Donegal, the forehead of the dog, that slice of country squeezed in next to the British annex. Did one of their ancestors come from Donegal, I wanted to know, or perhaps the Protestant North? This latter suggestion was shouted down. They, and we, were 100 percent Catholic Irish, my uncle insisted. To suggest otherwise was a dire insult.

Whatever their ancestry, my grandparents were staying, for a reason that will never be known, at a B and B in Buncrana. My grandmother was filing her nails at what she would later always refer to as an “armoire”—my father was very clear on that point—when my grandfather turned from the window and said, “I have the strangest feeling in my legs.”

She didn’t look up. She would regret this. Daniel, she would say to me later, always look up, if someone says that to you, always. I can confidently report that no one ever has. In the event, she did not look up. She kept on with the nail filing and said, “So sit down.”

He didn’t sit down. He fell down, right across the carpet, knocking over the nightstand and an ornamental bowl that my grandmother had to pay for before checking out. A brain hemorrhage. Dead in an instant. Aged sixty-six.

I have the strangest feeling in my legs. How’s that for your last words?

Long story short: my grandmother was of the generation that didn’t make a fuss. Didn’t create waves. They just swallowed whatever bitter pill life dealt them and got on with it. It would never have occurred to her to have her husband’s body flown back to the States, to be honored by his numerous offspring. No, she didn’t want to put anyone to any trouble, so she had him cremated the very next day, with the local priest in attendance. She did the deed, she checked out, and she came home. She had to pay an excess baggage fee to bring home his suitcase, a detail that always sent my father overboard with rage (he never did cope well with financial outlay of any sort). But what had happened to the ashes, nobody quite knew.

The plight of my long-deceased grandfather touched a raw nerve in me. I left the wake in a frenzy of disgust: it was somehow very typical of my family to go to the trouble of lugging home the clothes of a dead man but overlook his actual ashes. To have never asked my grandmother for the specific location of his final immolation. How could his remains have been forgotten, consigned to some lonely purgatory in a country where none of us had ever lived, alone, abandoned? No doubt I was imagining my own ashes being left to molder in some faraway place, my children never collecting them because they were permitted to see me only once a week, between the hours of 3:00 and 5:00 p.m., at a place of their mother’s choosing. Because whenever this paltry, unjust amount of time came around, their mother left a message with their father’s secretary to say the children were ill/on a school trip/had a test/ couldn’t make it that day. Because the legal system is irrevocably tilted toward the female parent, no matter how unfaithful or vindictive she is. Because, however hard the father tries—

I digress.

After I got back to San Francisco, I got hold of the names of all the funeral homes in that part of Ireland and, in between fielding calls from my lawyer, attending court appearances at which I might as well have thrown several thousand dollars into a trash can and dropped in a lit match, attending separate liaisons with my two lovers, trying to find an apartment where I could live when my friend returned from Japan (an eye-wateringly expensive three-bedroomed place because, the lawyer said, it was crucial to show I was “able to provide a home for the children”), I called them. I would sit at the kitchen table at 3:00 a.m., holding on to the end of a joint as if my life depended on it—and perhaps it did—and dial a number on my list. Then I would listen to the soft, cushiony vowels of the reply: “Hello.” Said more like hellouh: the closing sound elongated, the tongue lowered, farther back than it would have been in the mouth of an American. There was no “how may I help you?” follow-up either, just a matter-of-fact hellouh.

It took me a while to get used to. So, I would sit there in the dark, in my colleague’s kitchen, surrounded by crayoned drawings by children who weren’t related to me, insomnia raging through me, and I would ask: Can you help me, can you tell me, did you cremate a man called Daniel Sullivan thirty years ago, on a day in late May? Yes, to add to the surrealism of the situation, my grandfather and I have the same name. There were times, in the dead of the San Francisco night, when I felt as though I were trying to track down the ashes of my former self.

At my question, there was always a momentary pause and, after a scuffling, a few exchanges I was convinced were often in Irish, the thunk-swoosh of a filing cabinet being opened, the answer was always no. Said nooooo.

Until one day a woman (girl, perhaps—she sounded young, too young to be working at such a place) said: Yes, he’s here.

I held the phone to my ear. I’d been in court that day, where I’d been told I had no further recourse: there was nothing I could do to ensure I could be part of my son and daughter’s upbringing; there was no way to force my ex-wife to honor the contact agreement; I just had to hope “she would see sense”; and, in the words of my lawyer, we’d “come to the end of the road.” At which I roared, in the domed vestibule of the courthouse, so that everyone in the vicinity turned toward me, then quickly away, all except my ex-wife, who walked steadily to the exit, without looking back, and even the swish of her ponytail was triumphant: “It’s parenthood. There’s not supposed to be an end of the road.”

For something to come right, to have someone say, yes, here he is, seemed an impossibility, a tiny sweetener in all the oceans of bitterness in which I was currently drowning.

“You have him?” I said.

There was a slight pause, as if the girl was taken aback by my emotion. “Yes,” she said again. “Well, where is he?” I’d heard that funeral homes dispose of ashes if they are not taken away by relatives. I wanted to know where he’d been scattered, so I could tell the family, and we could decide what to do with Grandma.

But instead of saying, We chucked him out the back door, into the sea breeze, into the nearest rosebush, over a convenient cliff, she uttered the unbelievable sentence: “He’s in the basement.”

For a mad moment, I had an image of Grandpa pottering about in a low-ceilinged but pleasant space, dressed, as he so often had been, in slacks, a mustard-yellow shirt, and a bow tie, spending the last thirty years rearranging storage jars or setting up a Ping-Pong table or sorting nails in toolboxes or whatever the hell it is people do in basements. We thought he was dead, I would shout. But he’s just been in your basement all this time!

I cleared my throat and tightened my grip on the phone. “The basement?”

“Shelf four D.”

“Four D,” I repeated.

“When do you want to come and collect him?”

The question took me by surprise. It had never occurred to me that Grandpa would need to be fetched, like a child from a birthday party. I realized in that moment that I hadn’t really expected to find him: the whole thing had been a distraction for me during the lowest point of my life thus far. To have found him was discombobulating, unexpected, unreal.

Ireland: I pictured damp hillsides of vivid green, stone bridges arching over silvering streams, women with an abundance of auburn hair running their fingers up the strings of harps.

“Next week,” I almost shouted, “I’ll come next week.”

Which was how I ended up alone, in the middle of rural Ireland during spring break, ten years ago, alternately drinking myself into oblivion or eating takeout in a series of B and Bs with slippery bedcovers and single portions of milk.

I say “alone,” when actually I was accompanied by my grandfather, who was sporting a small taped cardboard box and occupied the passenger seat of the rental car. He and I got along very well, which was not quite how I remembered it when he was alive.

“Remember that time you spanked me with a hurling stick for sassing you at table?” I would say as we bowled across the Irish countryside, which looked surprisingly close to how I’d imagined it, humpbacked bridges and all. Lots of sheep, though: more than I’d ever thought possible.

Or: “How about that time you told my sister that no decent man would have her because she ate a lamb chop with her fingers?”

Grandpa kept his counsel. He didn’t even complain when I ground the gears on the stick shift or wavered to the wrong side of the road or ate only potato chips and Guinness for lunch or fired up a joint when it was way past my bedtime.

Then, one day near the end of my allotted fortnight, I was driving from the coast in the direction of the border. Grandpa and I were discussing whether or not we would head elsewhere to check out the scene—Galway, maybe; Sligo; or over the border to Ulster—whether or not we’d had enough of Ireland (I was pretty sure he had). I was rounding a bend when I caught sight of a child at the side of the road. Just crouching there, his chin in his palms.

There was something about him that didn’t seem quite right. I hit the brakes and backed up slowly, lowering my window.

“Hey, kid,” I said in my friendliest voice. “Everything OK?”

He stood up. He was barefoot, six or seven years old, and was dressed in a weird padded jacket thing that looked as though it had been made by free-spirited people under the influence of something fun. He opened his mouth and the beginning of a sound came out. It might have been “I” or possibly “my.” It was followed by silence. But not any kind of silence: a terse, freighted, agonizing silence. He stared intently at the ground in front of him, his jaw locked, his hands balled into fists. I could see his little chest struggling to draw in breath. He looked in my direction, then away. He was covering for himself pretty well, something I always find just heartbreaking: the bravery of it, the struggle, the small ways kids find to cope. The boy glanced skyward, in imitation of someone deep in thought or giving what he might say some consideration, but I wasn’t fooled. I had, a long time ago, been a research assistant on a program for stuttering, and I was remembering all those kids we worked with, mainly boys, for whom speech was a minefield, an impossibility, a cruel requirement of human interaction.

So I took a deep breath. “I see you have a stutter,” I said, “so please take as much time as you need.”

He flicked his eyes toward me, and his expression was incredulous, stunned. I remembered that, too. They can’t believe it when you’re so open about it.

Sure enough, the kid said, in the rushed diction of a long-term stutterer: “How did you know?”

He didn’t sound Irish, I wasn’t surprised to hear. He looked like a blow-in, a settler—I’d heard there were English hippies in the area.

I leaned on my car window and shrugged. “It’s my job. Sort of. Or it used to be.”

“You’re a sp-sp—” He stumbled, just as I’d known he would, over the term “speech therapist.” Ironically, it’s a phrase almost impossible for a stutterer to say. All those consonant clusters and tongue-flexing vowels. We waited, the kid and I, until he’d gotten out an approximation of the term.

“No,” I said finally. “I’m a linguist. I study language and the way it changes. But I used to work with kids like you, who have trouble speaking.”

“You’re American,” he said and, as he did so, I realized his pronunciation was more complex than I’d originally thought. There was English in there, mostly, but something else as well.

“Uh-huh.”

“Are you from New York?”

I took out a cigarette from the glove compartment. “I’m impressed,” I said. “You have an ear for accents.”

He shrugged but looked pleased. “I lived there for a while when I was little, but mostly we were in LA.”

I raised my eyebrows. “Is that right? So where are your mom and dad right now? Are they—” He interrupted, but I didn’t take it the wrong way: kids like him have to talk when they can, whether there’s a gap in the conversation or not. “We had a house in Santa Monica,” he blurted, not answering my question at all. “It was right on the beach and Maman and I went swimming every morning until one day the men showed up and Maman took the flare from the boat and she—she—she—”

He came to the end of this intriguing burst of articulacy and began to struggle in silence, cheeks red, the volatile confederacy of his tongue, palate, and breath dissolving into chaos and strife.

“Santa Monica is beautiful,” I commented, after a while. “It sounds like you had fun there.”

He nodded, his mouth shut tight, not trusting himself to speak.

“So you live over here now? In Ireland?”

He nodded again.

“With your mom? Your . . . maman?”

Another nod.

“And where is she? Is she”—I wondered how to put this without sounding threatening—“nearby or . . . ?”

He jerked his head behind him. “She’s back there?”

“Th-th-th-the . . . t-t-t-tire . . . bur-bur-burst.”

“Ah,” I said. “OK.” I pulled up the hand brake and got out of the car. I smiled at him but didn’t get too close. Kids can be jumpy, and rightly so.“You think she could use some help?”

Doglike, he dived into the bushes and reappeared on a track I hadn’t noticed. He grinned and set off, zigzagging one way, then the next. We went around a bend, then another, the kid shinning up a tree and down again, turning every now and again to regard me with amusement, as if it was a great joke that he had procured my company like this. At the approach of another bend, he dived again into the undergrowth. There was the sound of a rustle, a giggle, and then a woman’s voice: “Ari? Is that you?”

“I found a friend,” Ari was saying as I came around the bend.

Up ahead on the track a van was raised on one side with a jack. A woman was crouched beside it, tools spread out around her. The sun was so strong that she was just a silhouette, and her hair was so long that it brushed the ground.

“A friend?” she said. “That’s nice.”

“Here he is,” Ari said, turning toward me. The woman jerked her head around and rose up from the ground. At this point, I could only register that she was tall, for a woman, and thin. Too thin, her collarbone standing out like a coat hanger from her chest, her wrists a circumference that suggested to me she might not possess the strength required to wield those tools. She had a mass of honey-colored hair, and her mouth was screwed up in a displeased pout. She was wearing a pair of overalls, rolled up over a pair of mud-encrusted Wellingtons. She was not at all my type. I remember consciously forming this thought. Too skeletal, too haughty, too symmetric. She had a face that seemed somehow exaggerated, as if viewed through a magnifying glass: the features excessive, the eyes overlarge, widely spaced, the top lip too full, the head disproportionately big for the body.

She tilted her head, she spoke, she gestured: she did something, I don’t remember what. All I knew was that the next moment she looked perfect, startlingly so. This would be my first experience of her protean quality, the way she could appear to be a different person from second to second (a major reason, I’ve always thought, that cinematographers loved her). One minute, she seemed too thin and kind of bug eyed, if I’m honest; the next she was flawless. But too flawless, like the “after” illustration in a plastic surgeon’s office: cheekbones like cathedral buttresses, a mouth with a deeply grooved philtrum, pearled skin with just the right number of freckles across the impeccably tilted nose.

I’d later find out that she’d never darkened the door of a plastic surgeon, that she was, as she liked to say, 100 percent biodegradable. I’d also find out that the filthy overalls concealed a pair of stupendously pneumatic breasts. But, at the time, I was thinking that I preferred women with a bit of curve on them, women whose bodies welcomed yours, women whose beauty was flawed, unusual, held secrets of its own: a touch of orthogonal strabismus, a nose as ridged and stark as that on a Roman coin, ears that protruded just a touch.

The bony Botticelli bent down, picked up some kind of wrench, and brandished it at me. “Hold it right there!” she shouted.

I stopped in my tracks. “Don’t worry,” I said, and almost followed this with, I come in peace, but stopped myself just in time; might I be just a little bit stoned still? It was possible. “I mean you no harm.”

“Don’t come any closer!” she yelled, waving the wrench. Jesus, the woman was jumpy.

“It’s OK,” I said soothingly, holding up my hands. “I’ll stay right here.”

“Who are you? What do you want?”

“I just met the kid out on the road. He said you had a flat tire and I came to see if I could help. That’s all. I—”

She half turned, still keeping her eyes on me, and let off a long speech to the kid, in French. Ari replied and I noticed that he didn’t seem to stammer in French. Interesting, I caught myself observing. Non, Ari kept saying, in a slightly exasperated tone. Non, Maman, non.

“How did you find me?” she shouted.

“Huh?”

“Who sent you?”

“What?” I was confused now. We seemed to be stuck in a bad spy novel. “No one.”

“I don’t believe you. Somebody’s put you up to this. Who is it? Who knows I’m here?”

“Look,” I said, fed up now, “I have no idea what you’re . . . I was just passing and I saw a kid all on his own at the side of the road and I stopped to see if he was OK. He mentioned the flat and I thought I’d come see if you needed any help. By the looks of things”—I gestured toward the van—“you’ve got it covered, so I’ll head off.” I raised my hand. “You have a good day.” I turned to the kid. “Goodbye, Ari. It was nice meeting you.”

“G—”” he tried. “G-g-g—”

I looked him in the eye. “You know what you can do if you get tripped up by the first letter of a word?” Ari looked at me, with the trapped, ashamed gaze of a stutterer.

“Substitute something easier, something that launches you off on a different sound. I’ll bet,” I said, “that a smart boy like you can think of lots of other ways to say ‘goodbye.’”

I turned and headed off down the track.

Behind me, Ari shouted, “See you!”

“Perfect,” I threw back over my shoulder.

“Hasta la vista!” he shrieked, jumping up and down.

“You got it,” I said.

“So long!”

I turned and waved. “Take care.”

“Au revoir!”

“Adios.” I got around the first bend before I heard feet behind me.

“Hey!” she called. “Hey, you.” I stopped.

“Are you coming after me with your monkey wrench? Should I be scared?”

“What’s that you’re carrying? Is it a camera? I know it’s a camera. I want you to take it out and remove the film, here, in front of me, so that I can see you do it.”

I stared at her. My main thought was for Ari: Should he really be living with someone so totally loco? No wonder the kid had challenges with verbal fluency, living with a mother suffering such extremes of paranoia, such delusions, such fears. A camera? Remove the film? Just for a moment, though, as we looked at each other, something flickered across her face that seemed familiar: the slight dipping of her eyebrows into a frown. I’d seen that expression before. Hadn’t I? Did I know this woman? A disconcerting notion, when you’re in the middle of nowhere, thousands of miles from home.

“Is it a camera?” she insisted, pointing at my hands. I looked down and saw, to my surprise, that I was holding Grandpa’s taped box. I must have reached for it as I got out of the car. He’d always liked a little air, had Grandpa.

“It’s not a camera,” I said. She narrowed her eyes, for all the world like a police interrogator.

“What is it, then?” I gripped the now-familiar cube of cardboard, taped over its planes, slightly softened at the corners.

“If you must know,” I said, “it’s my grandfather.”

She pursed up her lips, raised her eyebrows: a minuscule arching inflection of her face. Really, it was too strange. Her face was so familiar, that expression so known: where had I seen her before?

“Your grandfather?” she repeated.

I shrugged. I was not, I felt, bound to provide her with any explanations.

“He’s been feeling a little under the weather lately.”

“Seriously? You carry him around with you?”

“So it would seem.”

She passed the monkey wrench from one hand to the other.

“Ari tells me you help children with speech impediments.” I winced.

“The term ‘impediment’ is generally considered to be a little pejorative. You might try ‘challenged.’ ” A diva-ish sigh. “Speech challenged, then.”

“Well, I did. A long time ago.”

Her extraordinary eyes—I’d never seen eyes like them; pale green, they were, with darker circles around their edges—flicked over me assessingly, desperately. Her exquisite porcelain face acquired an expression of vulnerability, and it was easy to tell that it was not an arrangement to which her facial muscles were accustomed. “You think he can be cured?”

I hesitated. I wanted to say I didn’t like the term “cured” either. “I think he can be helped,” I said carefully. “He can be helped a great deal. As a postgrad, I was involved in a research program to help kids like Ari, but it’s not strictly my line of—”

“Come,” she said, in the imperious manner of one used to being obeyed. I half expected her to click her fingers at me, like a dog owner. “You can hold the jack while I tighten the wheel and you can tell me about this program. Come.”

I thought: No, I won’t come. I thought: I won’t be bossed around by some hoity-toity madam. I thought: She’s used to getting what she wants because she happens to possess the face of a goddess. I thought: I will not come anywhere with you. But then I did. I steadied the jack while she replaced the wheel. I told her what I could remember about the dysfluency program while she turned the bolts. I looked away, with effort, when the hem of her shirt got separated from the waistband of her overalls. I did what a good man might do: I helped, then left.

Later that night, I was lying on the bed in the B and B, contemplating the remains of my dope stash, which wasn’t, I was realizing, going to last me until my return. How could I have neglected to buy enough at that dodgy bar in Dublin? I didn’t stand a chance in hell of getting any more around here. Would weed even grow in Ireland? I mused. Wasn’t there just too much damn rain?

There was a knock at the door, and my landlady, a Mrs. Spillane, a woman with hair that stood out around her head, like dandelion down, and an apron surgically attached to her front, stood there. I had hastily stubbed out the joint and done that pathetic smoker’s wave in front of me—why do we do that?—but her expression was that of a woman who knew she was being robbed but couldn’t yet prove it.

“Mr. Sullivan,” she said.

“Yes?” I said. I even pulled myself straighter, as if to withstand and refute accusations of getting high, alone, in the middle of nowhere, thousands of miles from home.

“This came for you.” She was holding, I now noticed, a small parcel, wrapped in a calico bag. “Thanks.” I put out my hands to take it, but she pulled it away. She glanced up and down the corridor, as if checking for the presence of the FBI.

“She wants to see you,” she whispered.

“Who does?” I replied, noticing that I, too, was whispering. It appeared to be catching.

Mrs. Spillane examined me at our new proximity. I wondered for a fleeting moment what she saw: a large American man, starting to gray at the temples, the whites of his eyes scribbled with red calligraphy? Could she read, in its runes, my jet lag, my long-term insomnia, a dope habit, and unassailable paternal grief? Hard to tell.

“She does,” my landlady said, leaning forward, attempting what seemed to be a wink.

Dope makes most people paranoid, but I couldn’t blame on the drug my ever-present sense that the world was against me: I’d had it even before I’d started out on this bender. What was she saying to me? Was I missing something?

“I’m sorry,” I began, “but I have no idea—”

She thrust the package into my hands. For a second, I had a mad notion that my ex-wife had somehow caught up with me and sent some noxious parcel: excrement, the semen of her lover, the severed head of the dog.

Then I looked down at the familiar blue tape bisecting some cardboard. It was Grandpa.

“Oh,” I said. “How did—”

“You left it beside her car. When you were helping her.” I clutched Grandpa to me. I remembered placing him to one side in order to winch down the jack, but how could I have forgotten to pick him up?

“Sorry, Grandpa,” I muttered. “God rest his soul,” Mrs. Spillane said sententiously, crossing herself. “Yes,” I said. “Thank you. Well”—I reached for the door—“I think I’ll turn in and—” Mrs. Spillane put her hand on the door to stop it from closing.

“She wants to talk to you.” She was whispering again.

“Who does?” She sighed, exasperated. “She does.”

“You mean the—the woman with”—I had, in my dope-addled state, to concentrate hard so as not to say the great rack—“the hair?” Mrs. Spillane put her face close to mine. She was frowning, examining me, as if she had been considering buying me but was coming to the conclusion that I had too many defects.

“Do you know how to find her?” she whispered, with another glance over her shoulder.

“What?”

Mrs. Spillane hesitated. “You don’t know?”

“Should I?” I said, wondering how long she and I could go on conversing in questions.

“She didn’t tell you?”

I was floored for a moment but then came back with “Why would she?”

Mrs. Spillane said, “Hmm,” thereby breaking the spell. She turned, abruptly, and said, “I need to make a telephone call.”

I was left there, with Grandpa, standing in the doorway. I shut the door and leaned my head into its glossy wood. Something about seeing the water-flow grain of it at such close proximity made a decision rise in me like sap: I’d had enough. This cryptic nonsense was my breaking point. Enough with the rain, the dope, the evenings alone, the carting Grandpa around. Instead of igniting the rest of that joint, I was going to pack and drive to the airport. I’d get an earlier flight home: I’d gotten what I’d come for, and I couldn’t take the surreal turn to the minds of the people here. I was a fish not so much out of water but way up the shore and over the beach road. I would leave Ireland and never come back. I would go home and try to repair what was left of my life.

I pushed myself upright. I crossed the room, flipped open my suitcase, and started tossing things into it. I was dithering about how Grandpa should travel—carry-on or checked—when there was another knock at the door. Mrs. Spillane stood in the corridor, as before: the apron, the hair, the crossed hands.

“She’ll be expecting you tomorrow,” she said, in a hushed, sepulchral tone. “The crossroads at ten.” “Huh?”

“I told her breakfast would be finished by eight-thirty, so you could come earlier, but Claudette said ten suited her best.”

“Hang on a second—”

“I’m to give you directions to the crossroads. I’ll have a map for you at breakfast.” She disappeared, stage right, and I was left staring at an open door. Typical, I thought, slamming it. A woman like that would naturally have a pretentious name.

“She couldn’t be called something like Jane or Sarah,” I ranted to Grandpa as I hurled books into my case.

“No, nothing like Amy or Laura or Clare. It would have to be something foreign and fancy, like Claud—”

Halfway through uttering her name for the first time, something gave way. It was as if the bricks and timber of an edifice were falling all around me. I suddenly saw, I suddenly remembered where I’d seen her before. She had been a dancer. Or was it a doctor? I’d seen her as an amputee, a murderess, a detective, a nanny. I’d watched her be French, Spanish, Italian, Persian. She’d escaped death and she’d died of cancer, car accidents, pneumonia, tiger attack. She’d killed and been killed. I’d seen her be fifteen; I’d seen her be sixty. She’d fought, punched, stolen, lied, cheated, saved lives, given birth, given head, shot, swum, danced, dressed, undressed, over and over again, for all of us.

To apply the word “famous” to her wouldn’t be entirely accurate. Fame is what she’d had before she’d done what she did; what came afterward went beyond, into a kind of gilded, deified sphere of notoriety. These days, she was known less for her films than for having vanished right at the height of her career. Poof. Ta-da. Just like that. Thereby making herself into one of the most-speculated-about enigmas of our time.

I don’t know if she’d thought ducking out like that would lessen her fame, but it had only the opposite effect. The press tends not to take such temerity lightly and the celluloid geeks—those oft-bearded types who will recite entire scripts at the drop of a hat, swap continuity errors, or spot background cameos by prefame actors—even less so. She was still, however many years on, the subject of much debate. They were always wondering how she had done it, why she had done it, where she had gone, if she was still alive, whom she might still be in touch with, and would she ever come back? They were forever trying to track her down, posting possible sightings of her on the internet, complete with smudged, grainy shots of someone who bore a passing resemblance to her. I’m not much of a moviegoer, but even I knew the contours of her story: her relationship with that director, their controversial collaborations, her tempestuous reputation, then her disappearance. Hadn’t she attacked some journalist or photographer? Didn’t she walk out in the middle of making some movie, causing some major studio to go into bankruptcy? Something like that. Whatever had happened, she had pulled off the thing that people of her ilk must dream about all the time: she’d left her life; she’d pulled the plug; she’d disappeared. And I had found her.

* * * *

There is a man at a desk. His head is bowed, forehead resting in his hands. The computer screen casts his hair, his clothes, in a cool, leucistic glow.

There is a man at a desk and the man is me.

I sit there, in my office, head propped on fists. I see: the edge of my desk, the nap of my trousers, the heels of my shoes, and, far below, a parallelogram of orange departmental carpet. I am still wearing my coat, still toting my bag. There is a vague smell off me, of offices, of crowded trains, of places I try to avoid. My bag jostles beside me in the chair, neither on nor off the ergonomically molded arm, as if fighting for its share of space.

From beyond the door comes the sound of students, rolling along the corridor, chatting, complaining, shoving one another. The click-clack of heels. An electronic plop as a phone receives a message. Someone saying, who would have believed me, anyway? in a cross voice.

The lecture is delivered. The words have been spoken, the sentence deconstructed. The students have been enlightened as to the difference between pidgins and creoles. They have the theory of creole grammar, hopefully, tucked into their heads. I stood in front of them for an hour. I moved through the lecture. I gave eye contact. I allowed time for questions. I did what I’d come here to do.

And now? I am meant to be leaving for the airport. I should be collecting my things, getting my desk in order, answering a few final e-mails.

Instead, I am unable to do anything besides sit at my desk. My mind zigzags, like a bluebottle, from Brooklyn to Nicola Janks, unable to settle on either one. My father, this goddamn party, and now this.

I raise my head. In the search box of my browser are two words. They have been there since I got back to my office half an hour ago.

“Nicola Janks,” my screen tells me, minuscule pixelations arranged to form the letters of her name. I don’t think I’ve ever typed it before, predating as it did the arrival of computers in my life. A strange thought, now, those years in which we existed quite happily without their constant presence.

The cursor, next to the s of “Janks,” flashes on and off, awaiting instructions, my tap on the return key, a faithful hound, ready to do my bidding, to retrieve whatever I request.

I’ve been sitting here all this time, debating whether or not I want to know. Whether or not I should hit that key. What will happen if I do, what will happen if I don’t? Will anything change, either way? The thought that swirls like flotsam on the surf in my mind is: please. Let it not be that year. Let it not have been then. Let her have died in the late eighties, the early nineties. Let her have made it into her thirties, comfortably so. Let her have had an accident, been hit by a car, knocked off her bike, fallen down a cliff. Let her have contracted some rare, incurable disease. Above all, let her have died quickly, painlessly, in the company of people who loved her. What more, after all, can any of us ask?

Just let it not have been in a forest, alone, in the velvet gray of dawn. Please.

When I was a kid, I used to love doing those puzzles where you get a page scattered with seemingly random dots. You have to connect them, number by number, with a pencil line, drawing form out of chaos, eliciting sense from mess. The part I liked best was about halfway through, when you could look at what you’d done, and what was to come, and try to guess what it was. A rocket? A tractor? A palm tree, a sailboat, a dinosaur, a beach? It could be anything. The best ones were those that misled you. You thought it was going to be a railway engine, but it resolved itself into a dragon with smoking nostrils. You thought you saw a cat, but all along you were drawing an iguana.

That same feeling of dislocation between what you thought you were doing and what you actually did envelops me as I sit there, as I press my elbows into the surface of my desk. All along I’d thought my life had been one thing, but it now seems it might have been something else entirely.

I unloop the bag from my neck and let it fall to the floor. I reach for my cigarettes, I loosen my tie, I twist my chair around, I shift some papers from one side of the desk to the other, and then, quickly, before I can stop myself, I turn my chair back around and hit the return button. I hit it hard. My finger joints throb from the impact.

The timer icon appears, tiny grains of electronic sand slipping through its waist. It flips itself, once, twice. Then a blue list appears. Library catalogues, mainly, from universities. Numbers and codes for academic papers by her, a link to a textbook she coedited, a mention of the radio program heard earlier, with an option to download the podcast. This, my eye sees, has a link for a biography, so I click on that and it unscrolls before me, the short life of Nicola Janks.

A novena of birth, nationality, schools, degrees, teaching posts, publications: how strange it is to be distilled in this way, as if we are in the final analysis just geography, coordinates, output. Is this what will be left of us all—computer-coded facts?

The four numbers at the biography’s end slide into me, like a cold blade. That the year of her death is, indeed, 1986 seems at once devastating and inevitable. Of course, I think, of course it was then. I knew it already, I find. Perhaps I always did.

Five minutes later, I am moving across the gray concrete slabs that separate the university from the rest of the world. I need some air, a walk, a change of scene. I need to find a cab. Something like that. I cannot stay in that box of an office with my screen staring back at me. I have three cigarettes rolled inside my tin and I intend to smoke them, one after another, before I go to the airport.

I am moving along a bridge, the traffic grinding in contraflow along the pavement edge. There is roadwork ahead, a vat of boiling tar giving off a choking stench and great clouds of smoke. The river beneath is brown and swollen with rain, lapping oily waves at its banks.

When I reach the other side, there is a bench. I sit myself down on it. I start searching my pockets for a lighter. I have time, I tell myself, taking a snatched glance at my watch. Plenty of time. I am just going to take a short moment to steady myself, and then I am going to press on.

The bench is in one of those small parks—marooned green spaces that fill an empty lot on a street and you wonder, in this city, what might have happened there, what crisis could have occurred to clear the area of buildings. And it seems to me, as I sit there, among the ornamental hedges and genuflecting chrysanthemums, as I spark my lighter with a shaking hand and inhale the smoke, that my life has been a series of elisions, cover-ups, dropped stitches in knitting. To all appearances, I am a husband, a father, a teacher, a citizen, but when tilted toward the light I become a deserter, a sham, a killer, a thief. On the surface I am one thing, but underneath I am riddled with holes and caverns, like a limestone landscape.

A taxi, I am intoning to myself. I need to find one, then get a flight to Brooklyn, my sisters and my dad. I need to get on a plane and spend a few days there. I need to be at that party—and then? Then I come back here. Then I stay on track and get on with the life in hand. Then I do not start poking around, finding out whatever the hell happened to Nicola Janks, going off to uproot the truth. It is over and done. The woman is dead. Twenty years or more have passed. I am not going to drop myself down, like a speleologist, into those holes and caverns and start digging around. I have to focus, have to stop trembling, slow my galloping pulse. I have to put Nicola Janks on a shelf for a while, find a cab for the airport, and get my head around spending the next few days with my dad and—

There is a movement to my left. A man and his child, a girl, are sitting down on the bench. I glimpse a pair of scuffed trainers, the ones with flashing lights on the soles, trousers with the hems rolled up. The phrase “room for growth” floats unbidden through my mind as I turn to look at them. There is the girl; there is the father.

It is the child who draws my gaze. She is standing, one arm outstretched. I see that the arm is twisted and held out like that because she is scratching, in the desperate, driven, focused way that only an eczema sufferer can. She is tearing at her inner elbow, fingernails clawed and intent, seeking relief, seeking to feel something, anything, other than the torment of her condition. I see the grim determination of the child’s gaze, concentration under suffering.

Here, then, is another hole, another cavern in the life of Daniel Sullivan. Perhaps the largest, most devastating of all. I have to push off from the bench, to move, to force myself away, so great is the grief that has torn through me. I set one foot in front of the other, again and again, putting distance between me and the pair in the park. I have my gaze set on the road. I am treading carefully, as if the ground beneath me is not as firm and sure as it looks, as if it is riddled with underground rivers, as if at any moment a sinkhole may yawn open under my shoes. I am looking out for the lit sign of a cab. I have lost or dropped my cigarette somewhere along the way. The sensation that begins at my feet and trembles all the way through me is akin to the beginning of a seismic event.

Before I leave the park, I will permit myself one last glance at the child by the bench. I tell myself this as I move away. I see a cab, I signal, and it slows down. Just before it reaches me, at the curb, I turn. The girl is crying; the father is bent over his bag, searching for a cream, a lotion, anything. I crane my head to see, and the movement causes something to poke me in the ribs. I feel inside the pockets of my jacket, my palms sliding along the silky, slippery lining. My fingers encounter the reassuring rectangle of my passport. Folded into it will be my ticket. A flight to the States, my first in five years, a return to the house of my father. There it is, in my breast pocket, directly above my thudding, tripping, treacherous heart.

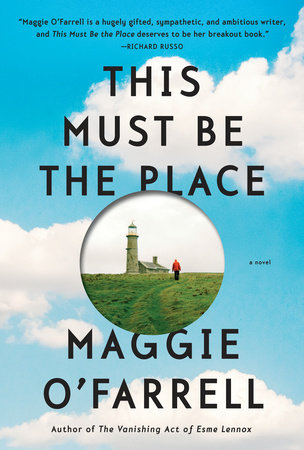

From THIS MUST BE THE PLACE by Maggie O’Farrell, copyright © 2016 by Maggie O’Farrell. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin

Random House LLC.