This is How You Write a Collaborative Essay

Patrick Madden (and 5 Other Writers) Try an Experiment

I’ve been thinking recently about how we are suddenly so wary of contact and contagion, and wondering if perhaps the COVID-19 pandemic and preventative measures will bring into our foremost consciousness the oft-ignored fact that we rely on each other deeply. We are gregarious animals, so specialized that each of us becomes helpless without the complementary specializations of our neighbors.

I want to be more aware of this fact as regards my writing. Anyone who’s browsed the acknowledgements pages in a book understands that writing, a seemingly solitary activity, requires the assistance and influence of an unending network of people. I think I’ve always known that I depended on others, teachers especially, and family and friends, but in my latest book, for reasons playful and pedagogical, I wanted to make explicit this dependence.

So I asked 15 writers I admire to intrude upon my personal essays with a paragraph of their own or some other subversive interruption. The analogous model I envisioned was a guest vocal performance on a song, thus these friends would be credited as “featured” writers in the essays. For example:

“Distance (feat. Joni Tevis)”

“Insomnia (feat. Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas)”

“Laughter (feat. Jericho Parms)”

“Plums (feat. Matthew Gavin Frank)”

“Thumbs (feat. Wendy S. Walters)”

And many more.

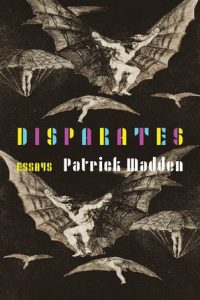

Given the overarching idea suggested by the book’s title, Disparates, which I mean in the Spanish sense of “nonsense, inanity, drivel,” I expected these guest-written passages to be reveling as well as revealing. I was not disappointed. And so I have asked the writers listed above to join with me once again to write this article, in which we consider the process and results of our collaborative experiment.

On the matter of collaboration in writing generally, each felt roughly as I do. “I’ve never collaborated in a text like this,” said Wendy S. Walters, “though I have engaged in a number of textual dialogues with other writers.” Jericho Parms concurred: “I think there is a fine line between being a writer working in collaboration and being a writer in conversation with others.” For Joni Tevis, “this has been mostly about collaborating with other texts, pieces of music, images, historical moments.”

Maybe we all find common ground in the way the personal essay focuses on the writer while acknowledging the writer’s insignificance.

Likewise for Matthew Gavin Frank: “The act of conducting research for an essay, and then essentially and inescapably filtering that research—interacting with it, arguing with it, greeting it with bemused silences, fanning what one may perceive to be its secret flames—can be, in part, a collaboration with other scholars, places, people, landscapes, ghosts.” Because I’ve been trained in the Montaignean form of essay, with its constant conversations with ancient sages, I utterly agree.

Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas, too: “I do nothing on my own or of myself. I collaborate all the time, I feel. Everything is borrowing or theft. Awareness of the interplay between invented reality and the reality of invention is what makes this genre such a sharp blade to play with. It’s also good to poison the ego. The ego is the enemy of confession.”

Which is a somewhat different position from E. B. White’s “I have always been aware that I am by nature self-absorbed and egoistical; to write of myself to the extent I have done indicates a too great attention to my own life.” Or maybe we all find common ground in the way the personal essay focuses on the writer while acknowledging the writer’s insignificance. At least that’s the way it’s been for me, over the years, as I’ve learned how much I lean on others, how unimportant I am in the face of all that is.

And while my earliest intention in inviting others into my essays was mostly an amorphous desire to goof around, the project did quickly become a letting go, a relinquishing of control, and thus an ego diminisher. It was also an avenue to all kinds of insights about writing.

For instance, Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas, who was once my student in a number of undergraduate writing classes at Brigham Young University, points out, when discussing the particulars of interrupting my essay on insomnia, that

the truth is, we’ve been collaborating a long time, and I’ve been writing my words between yours for a very long time too. I was about 21 when I first took your workshop, and I didn’t know what essays even were before that. I had just had a catastrophic knee injury and I thought my whole world was slowly ending with a snap and a whimper. I couldn’t leave the US because I couldn’t afford the ticket back [from Colombia], but your class took me back, and eventually it also took me away.

Which seems like a truly worthy result, the kind of meaning a writer hopes for when he sets out to gather influences into some slight, new thing. It is worth mentioning that Lina chose not to write additional material within my essay, but to create an erasure text from my essay. Despite challenges (artistically self-imposed) that “greatly limited what [she] could lift from the text,” Lina tells me that she “had this image of Ander Monson thinking about snow while sitting in a red wheelbarrow, so I pressed on trying to fit my sincerity inside yours, trying to think of spaces within spaces and facts inside facts, … telling the truth about my own life with your words.”

Most of my other friends intersected and inhabited my essays largely as I had imagined: they wrote interstitial paragraphs responding in their own voices, with their own experiences and thoughts as material. Wendy S. Walters, for instance, shared space with Elena Passarello in my “Thumbs” essay. While Elena wrote numerous song lyrics replacing some with thumb(and vice versa), Wendy broke in with a somewhat dark, mysterious paragraph.

Of the experience, she said, “the piece was so quirky that I felt right at home in it. I chose the essay because the topic seemed small and absurdly immense in its potential implications. … It’s such an interesting way to think of an essay—that it’s not entirely finished until another writer engages with it.”

I’m grateful and glad that my friends agreed to write featured parts of my essays, and that we wrote this piece together.

Joni Tevis chose “Distance” not because she loves the Bette Midler song “From a Distance” (which I refer to in the essay) but because it reminded her of “the way Bob Ross enacted distance through blurring the paint. He has a very on-purpose way of doing it, and it really does make something look like it’s far off. From a distance—actually it’s not misty, it’s a decisive, thoughtful thing!” As is inviting intruders into one’s essays. It’s worth noting that Joni’s “interruption,” much to my gleeful surprise, is longer than my original, thus appropriately flipping any supposed hierarchy.

Matthew Gavin Frank “gravitated toward the ‘Plums’ essay for its exhilarating meandering, its willingness to chase blind alleys, but also for its wistful sensuality and its willingness to intrude on itself and the fabric of the memories therein.” Matt points to a moment in which the essay unstitches itself, saying “I knew I wanted to come in at the point wherein Pat-as-narrator makes that direct address, asking for forgiveness.” He continues, addressing me:

I wanted to use this plea as a springboard into a series of my own memories that were, as rendered, stylistically inspired by your work in this essay, but also served as associative foils to the content of your sentences. I guess I was just excited to have this kind of conversation with you, Pat. You and I having a conversation. Your persona and my persona also having a conversation.

The nap I took in my “intrusion” was a real nap, and the dream I had was a real dream, the content of which shows up in shards in the piece. I knew I had to use this dream, and the act of dreaming itself, as a way of writing my way out, turning my volume down, going silent and, in the next paragraph, it’s Pat again who is the one who wakes up, and who, in turn, wakes us up.

Jericho Parms found the exercise of occupying my “Laughter” essay fun and challenging because her paragraph about laughing uncontrollably upon hearing her unborn son’s heartbeat for the first time was, she says, “pretty personal, and I was keenly aware that your existing essay was personal as well.” She recalls further,

I realized I was looking for clues, instruction, assurance that I really had been invited to insert my own voice into your essay. In the end, there were a couple of small markers in the text that served as entry points for me. First was a seemingly random reference to a date in history that happens to correspond with the month and day of my son’s birthday (and yours, of course). Second, was the sense of wordplay in the descriptions of Balderdash, which led to my own mind playing with initials and acronyms as they appeared in my paragraph. …

I decided to trust the process of essaying, to accept the trial, and potential error, of seeking meaning through shared human experience. Laughter was as good a topic as any to support that attempt as it is itself a burst of feeling, an expression and gesture we cannot always control, that often occurs and embodies both the warmth and welcome of an invitation but also the messy rudeness of an outburst or interruption.

Fitting sincerities inside others’ sincerities, finishing via others’ engagement, enacting distance decisively and intentionally, waking others up, embodying both warm welcome and rude interruption: all appropriate metaphors/realities to describe not only the guest-enhanced essays of my collection but all essays.

I’m grateful and glad that my friends agreed to write featured parts of my essays, and that we wrote this piece together, too, because I have truly learned more about collaboration and about the ways in which we are all connected, we all need each other.

__________________________________

Patrick Madden’s Disparates: Essays is available now from the University of Nebraska Press.

Patrick Madden

Patrick Madden is the author of three essay collections, Disparates (2020), Sublime Physick (2016), and Quotidiana (2010), and coeditor of After Montaigne: Contemporary Essayists Cover the Essays (2015). He teaches at Brigham Young University and Vermont College of Fine Arts.